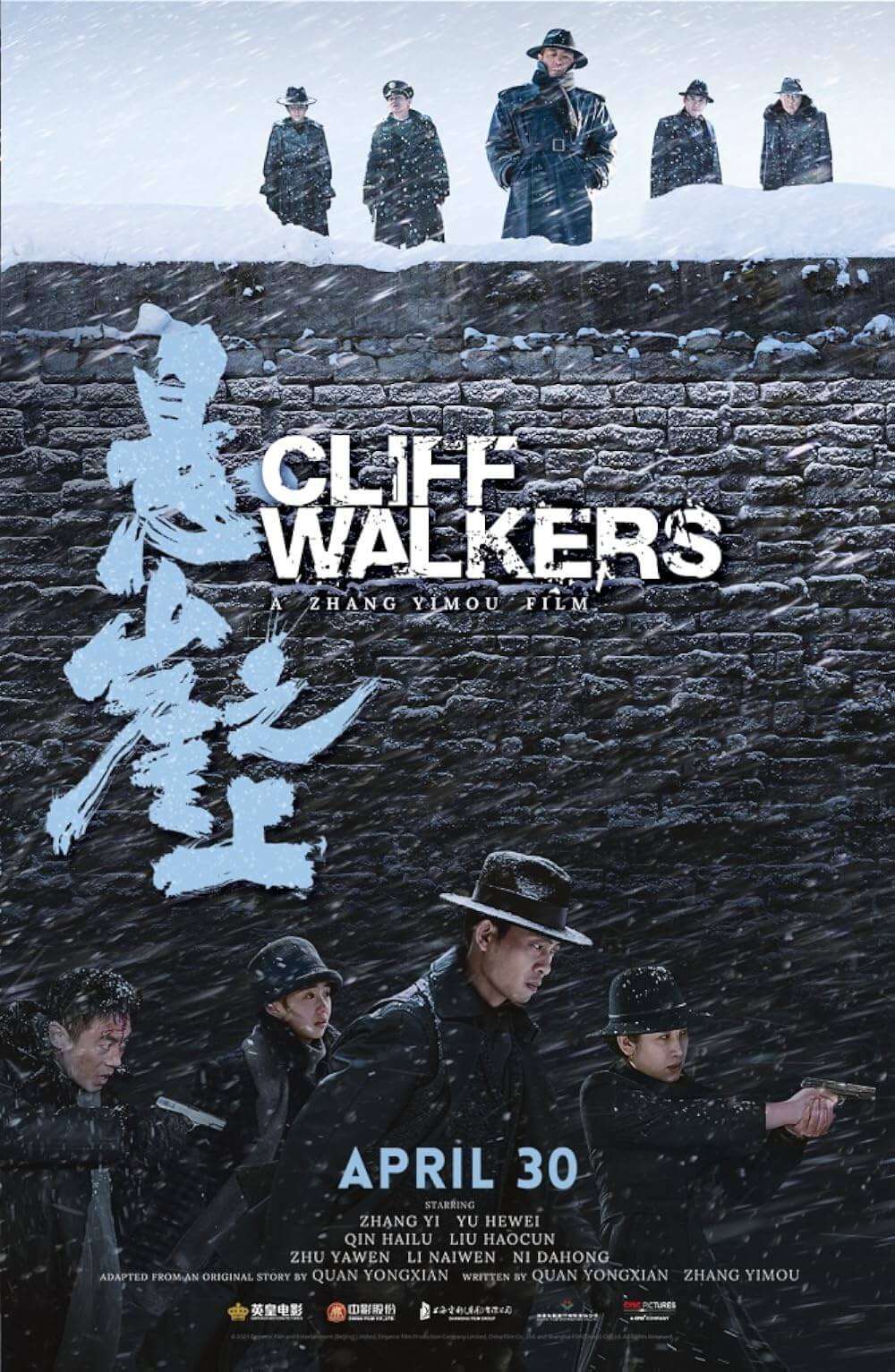

Cliff Walkers

By Brian Eggert |

Zhang Yimou makes his first foray into the espionage genre with Cliff Walkers, a stylish and often gripping entry in the preeminent Chinese filmmaker’s mercurial career. Set in the early 1930s, the film follows a crack team of spies on a dangerous mission: rescue Wang, a survivor and escapee from the secret Japanese camps located in Northern China, the site of untold death and human suffering, so that he can alert the international stage to the existence of the camps. Zhang and Quan Yongxian’s screenplay meets every expectation of the spy thriller along the way, dazzling the viewer with riveting sequences and twisting plot mechanics. Unlike anything in Zhang’s career thus far—it’s far more stylized than his period pieces of the 1990s, such as To Live (1994), and far removed from his wuxia adventures of the 2000s, such as Hero (2002)—Cliff Walkers demonstrates a filmmaker in full control of his craft. Though some viewers may take issue with its ideological underpinnings, the film’s immediacy and skilled presentation cannot be ignored.

The film opens with disorienting first-person shots of spies descending via parachute into the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo, formerly Manchuria, where they land among trees and in knee-deep snow. Immediately, the four-person crew—an older married pair, Zhang (Zhang Yi) and Yu (Qin Hailu); the younger Chuliang (Zhu Yawen); and the inexperienced Lan (Liu Haocun)—distributes cyanide pills in case of capture. And based on the duplicity of their first contact, chances are those pills will come in handy. Indeed, they’re headed to the city of Harbin, a nest of spies, to carry out their top-secret mission, codenamed “Utrennya,” named after the Russian word for “dawn”—a symbol for the idyllic end of their conflict. In Harbin, enemy agents await around every corner, and no one can be trusted. Later in the film, there’s a pitch-perfect shot in which one spy burns a written message in his hand, and his dexterous fingers avoid the heat by maneuvering the burning paper until it’s gone. The entire film blazes along, and the characters keep moving to avoid catching fire.

If the title is any indication, the central mission is fraught with danger from every side, even within. It’s a yarn worthy of Alfred Hitchcock’s wartime spy thrillers, complete with double agents, coded messages passed on bathroom walls, and moles entrenched high in the ranks on both sides. There are shootouts in the streets, hand-to-hand combat, car chases, desperate strangulations, elaborate deceptions, brutal scenes of torture with electricity and psychedelics, double-crosses, and plot twists galore. Zhang’s debt to Hitchcock is evident from an early train sequence worthy of The Lady Vanishes (1938), when a female comrade disappears on the way to Harbin. Similarly, the costumes resemble Brian De Palma’s glamorized vision of the 1930s in The Untouchables (1987)—the characters don expensive couture, including fedoras, long coats, scarves, and suits. Production designer Lin Mu has conceived a romantic vision of the past, to be sure, but not without a touch of harsh reality. Scenes at a Japanese camp show soldiers shooting suspects to encourage others to talk. And while the film leans into the more exciting components of the spy genre, the narrative density may prove too intricate for those looking for pure escape. Then again, it’s also the sort of film that, when someone sets a gun down on a table next to a corkscrew, you just know that corkscrew is going to end up in someone’s neck.

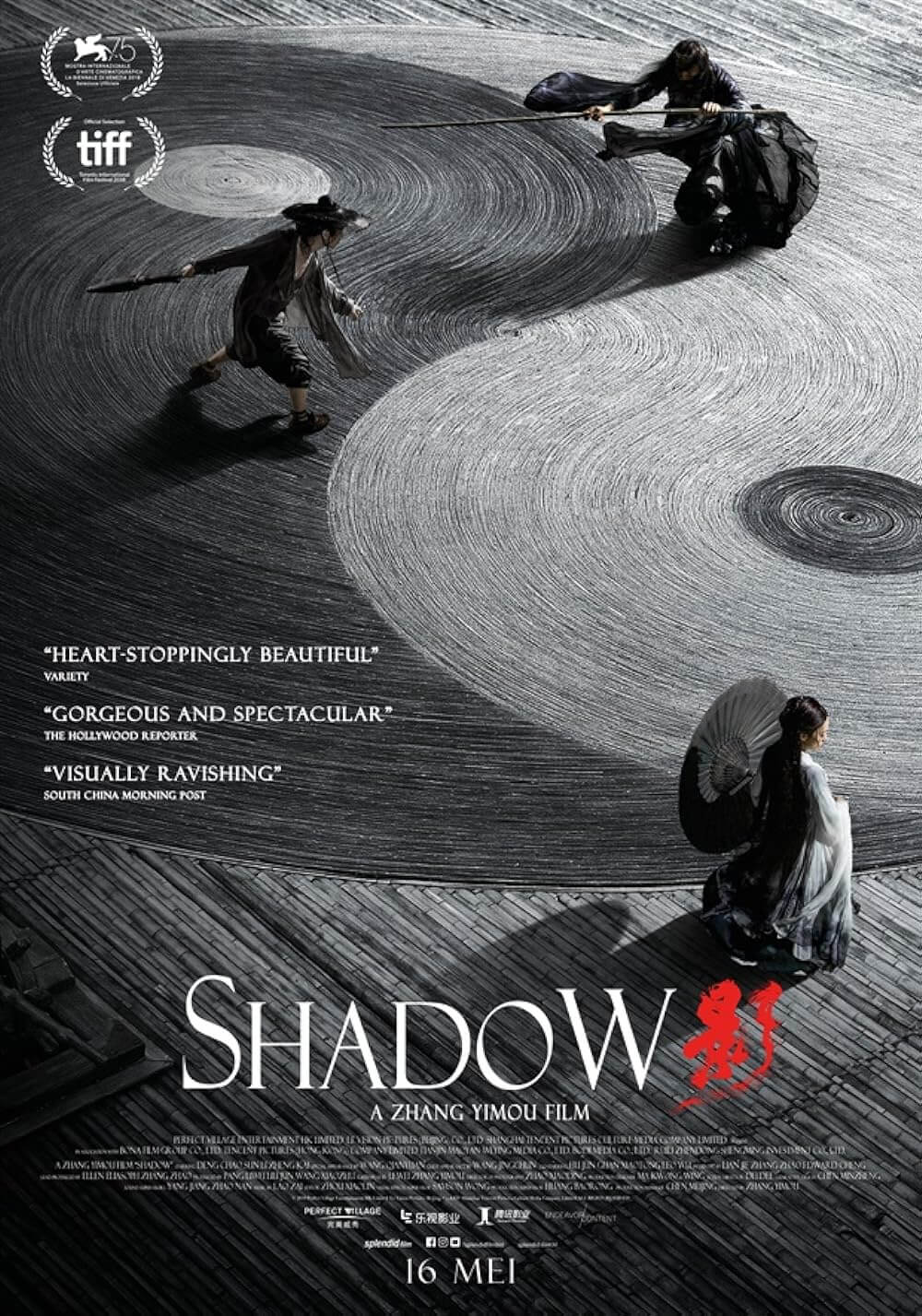

Cliff Walkers is Zhang’s first film to reach the United States since 2018’s superb Shadow. In-between, the filmmaker made One Second (2019), which was poised for an international debut at the 2019 Berlin Film Festival before being suddenly withdrawn—a move by the Chinese government widely interpreted as state censorship. By contrast, Zhang’s latest could be considered a sanctioned export. Recently, Xi Jinping, General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, has toured his country, celebrating the party’s centenary in 2021 by commemorating old battlegrounds and remembering past atrocities. Cliff Walkers falls in line with these events, complete with an end credits dedication to “the heroes of the revolution.” Some Western critics have focused their attention against these sentiments out of disdain for propaganda or perhaps the source of the propaganda. But when the USA fills international theaters with cultural colonizing products from Captain America movies to the latest Clint Eastwood flag-waving fare, we can hardly point fingers.

Cliff Walkers is Zhang’s first film to reach the United States since 2018’s superb Shadow. In-between, the filmmaker made One Second (2019), which was poised for an international debut at the 2019 Berlin Film Festival before being suddenly withdrawn—a move by the Chinese government widely interpreted as state censorship. By contrast, Zhang’s latest could be considered a sanctioned export. Recently, Xi Jinping, General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, has toured his country, celebrating the party’s centenary in 2021 by commemorating old battlegrounds and remembering past atrocities. Cliff Walkers falls in line with these events, complete with an end credits dedication to “the heroes of the revolution.” Some Western critics have focused their attention against these sentiments out of disdain for propaganda or perhaps the source of the propaganda. But when the USA fills international theaters with cultural colonizing products from Captain America movies to the latest Clint Eastwood flag-waving fare, we can hardly point fingers.

After all, Cliff Walkers acknowledges the camps where upwards of 10 million people died under Japan’s imperial army. The vast and disturbing history of Japanese camps and their eradication of Chinese, Indonesian, Korean, and Filipino peoples, not to mention allied POWs, is often overlooked by Western armchair historians of World War II. But those cultures affected have scars as well. Certainly, Zhang’s film could be accused of exploiting that history for the country’s political agenda. However, the few inklings of Communist-centric messaging remain negligible and hardly impede on the film’s forward momentum. Along with the aforementioned dedication, the spy characters quote The Communist Manifesto and pledge their devotion to its ideology (“Proletarians of the world, unite!” they declare), and their party is shown as the good guys in a fight against Japanese bad guys. Set those moments aside, and you have yourself a tense, expertly crafted cloak-and-dagger scenario that propels you from one familiar situation to the next.

Those who gravitate toward spy-thrillers will appreciate Zhang’s full commitment to the genre’s usual trappings. Zhang and cinematographer Zhao Xiaoding capture incredible chase scenes in Harbin, including a dazzling foot chase down alleyways shot from overhead, with snowy power lines between the action and the camera for a distinct visual pattern. The nighttime car chase, during which headlights illuminate the snowfall, is downright masterful thanks to the credited “Action Director” Jung Doo. Moreover, there’s nary a moment that looks artificial—unlike, say, most of Zhang’s The Great Wall (2017). As a Minnesotan, I watched the first snowy sequence and appreciated how the actors look cold, the snow looks deep, and the fur attire looks adequate at best. There are other pleasures, such as Cho Young Wuk’s excellent score that manages to evoke Ennio Morricone at times and Bernard Herrmann at others.

The material might play with all the warmth of a John le Carré novel until a final scene, which rings of sentimentality. Yet, it has a surprising impact as Yu and Zhang’s two children, who have been living on their own for years since Japan’s invasion, are reunited with a parent. If there’s a film to match Zhang’s unlikely balance of espionage adventure and sobering historical reflection, it’s Paul Verhoeven’s Black Book (2006)—both that film and Cliff Walkers grapple with real-life atrocity yet somehow manage escapist action, which may prove incongruous for some. The dynamic is never more evident than when editor Yi Yongyi cuts from a horrific scene of Japanese soldiers executing prisoners to a blithe shot of Charlie Chaplin performing his potato dance routine from The Gold Rush (1925) in a Harbin theater. Regardless of its ideology, Zhang’s handling of the assorted moods and set-pieces is nothing short of impressive, offering an energetic film that crackles with action and quickens the pulse.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review