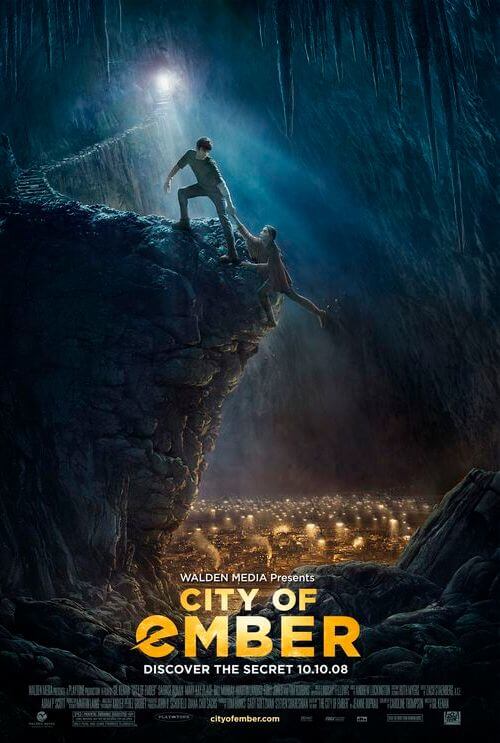

City of Ember

By Brian Eggert |

Built by idealistic scientists bent on saving humanity from apocalyptic destruction coming from above, the underground village in City of Ember takes the shape of most early pre-industrial European towns, in that it’s circular. This makes the occupying community more, well, communal; places the Mayoral leadership (Bill Murray) at the center; and also encloses the few hundred inhabitants within a nice, safe bubble. Looking like the children’s version of Brazil-meets-1984, leaky pipes run wild like vines, ancient wires barely conduct electricity, light bulbs glow with a faint hum, and the generator powering it all seems to flicker more and more as of late.

This is the home of Lina (Saoirse Ronan) and Doon (Harry Treadaway), two friends who find Ember’s failing power source none-too-promising. As luck would have it, Lina’s great-great (maybe there were more greats, I didn’t pause to count) grandfather was the Seventh Mayor of Ember, and he left behind a metal case, glowing with a red digital readout counting down the 200 years the scientists, called “the builders” by Emberites, deemed survivors should stay down there (so says the prologue). The time is up, and the city can no longer maintain itself. And so, in the tradition of The Goonies and National Treasure, the scientists have left a series of puzzles and clues that Lina and Doon must follow to escape before Ember’s lights go out for good.

Keeping pace by offering impressive set designs and a bright cast, the film capably steers our attention, involving us in the clues and the fates of our fine performers. Aside from Ronan, who continues to make an impression after last year’s Atonement, and the serviceable Treadaway, familiar faces appear around every corner. Toby Jones (from The Mist and W.) plays the assistant to Murray’s ignoramus Mayor. Tim Robbins appears as Doon’s father. And Martin Landau plays Sul, a veteran pipeworker. None of them can compete with our curiosity in the setting, however.

Inexplicable giant creatures, including overgrown moths and a man-eating mole the size of a rhinoceros, dwell on the outskirts and beneath the city. Whatever unnatural event caused their mutations isn’t described, though the film specifically points out that their sizes are larger than they’re supposed to be. Were those explosions we heard in the opening nuclear blasts, resulting in radiation-fed mutations? And if so, what else is awaiting the survivors when they inevitably get up there?

And as long as I’m asking questions: How did “the builders” find enough time and resources to construct the underground metropolis with the apparently sudden catastrophe occurring on the topside? Is it quite easy to assemble such a place? Who replaces the lights on the top of Ember’s cave when a bulb burns out? How did they get the canned pineapple to last two-hundred years? Why are the Emberites so dependent on electricity, and why haven’t they learned to create fire? That I was asking myself these questions during the picture and not afterward doesn’t speak well for the intended escapism.

Based on Jeanne Duprau’s novel, the story’s science fiction foundation becomes nothing more than your run-of-the-mill adventure yarn, abandoning its thought-provoking ideas for something much less satisfying. Mysteries are fun to solve, but when you know the inevitable conclusion from the outset, that the people of Ember were always meant to resurface, the mystery is rendered pointless. What if when the children found their way out, they found themselves on an alien planet? Or discovered they were just part of some horrible social experiment to determine how the masses are sheep following a shepherd? These ideas are best kept for another movie, of course, one decidedly not rated PG. The point is that The Wow Factor is hardly effective when there’s no mystery involved.

While City of Ember isn’t another children’s fantasy involving magic wands and prophesied saviors, the refreshingly dark doomsday circumstances are played out to an entirely lackluster effect. Directed by Gil Kenan (Monster House), the film’s third act abandons its unfolding mystery and instead relies on a poorly rendered computer-animation boat ride over collapsing waterwheels (Yippie?). The film gets too big for its britches, in other words, and fails to thoroughly explore its enclosed little world, which is frankly more interesting cinematically than the bland surface they escape to.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review