Christopher Robin

By Brian Eggert |

Disney has been emptying the hunny pot of writer A.A. Milne and illustrator E.H. Howard’s beloved creation Winnie the Pooh since the 1960s, decades after Milne first created him in 1928. They began with a series of theatrical shorts, then continued to multiple television series, a handful of feature films, along with spinoff titles such as The Tigger Movie (2000) and Piglet’s Big Move (2003). Among the best and most timeless adaptations was their last journey to the Hundred Acre Wood, 2009’s simply titled and 2D-animated Winnie the Pooh, an imaginative adventure of the absent-minded stuffed bear, who drops the occasional profound adage that makes us think. “I used to believe in forever,” said Pooh Bear in one of Milne’s original books. “But forever’s too good to be true.” Whether he’s waxing philosophical about the importance of seizing the moment or chasing his red balloon, Pooh epitomizes an easygoing sweetness, offering a sort of Anglo-Saxon version of the Japanese kawaii aesthetic.

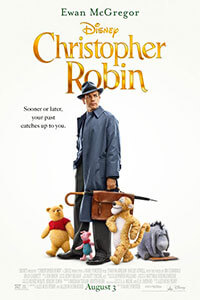

Christopher Robin, Disney’s latest attempt to reintroduce Pooh to a new generation, follows their recent trend of creating so-called live-action versions of their classic animated intellectual properties, including Alice in Wonderland, Maleficent, Cinderella, The Jungle Book, and Beauty and the Beast. “Live-action” is a term best used sparingly with these titles, since most of them rely on copious amounts of CGI animation to render their storybook worlds around the occasional living, breathing performer. Director Marc Foster adopts a style similar to David Lowery’s more restrained use of special FX on 2016’s Pete’s Dragon, placing fantastical creatures in the real world instead of a few human characters against a green screen backdrop. And so when the titular character, played by Ewan McGregor, returns to the childhood stomping grounds of his imagination, Pooh, Tigger, Piglet, Eeyore, and the rest look like stuffed animal versions of themselves, while Rabbit and Owl appear as photo-real talking animals.

The screenplay and story are credited to five writers, although the film’s distracting resemblance to Jon Favreau’s holiday classic Elf earns a raised eyebrow. In Elf, a comical fish-out-of-water tale unfolds as an innocent, magical character makes his way to the big city to rekindle his relationship with a distant loved one, who has since become a curmudgeonly and officious executive that no longer appreciates the simple joys of life and play. Gradually, the innocent and warm-hearted citizen of a mythologized land melts the cold heart of the executive, who, in a climactic scene, must tell off his bosses and choose family over his career. This basic plot trajectory perfectly describes Christopher Robin, with the grown-up boy from Milne’s storybook now a cynical World War II veteran who slaves away in postwar London as an efficiency expert at a luggage factory. His boss, the cartoonishly cruel Giles (Mark Gatiss), demands that Christopher Robin work rather than visit the family cottage of his childhood, thus requiring that he commit another in a string of broken promises to his frustrated wife (Hayley Atwell) and daughter (Bronte Carmichael), who visit the cottage without him.

But when the overworked Christopher, now bereft of hope or imagination, accidentally spills honey in the kitchen, he awakes the sleeping Pooh (voice of Jim Cummings). Unable to find his band of plush friends, Pooh travels from the woodland to London to remind Christopher that he, too, was once a child. Unfortunately, the first hour of Christopher Robin is a drab, unpleasant affair, wherein the agitated executive often loses his patience or yells at Pooh Bear—a bastion of purity and innocence that, when exposed to bureaucratic cruelty or impatience, betrays Milne’s intent for the character. Such scenes feel blatantly manipulative and designed to bring us way down, when, inevitably, tender moments a few scenes later bring us up and warm our hearts. McGregor transitions from an obsessed professional to a delightfully silly chap quite easily, but the amount of time spent on establishing Christopher Robin’s dour state feels out of balance with the last forty-or-so minutes of his restoration to humanity.

Forster, responsible for wildly incohesive material from The Kite Runner to Quantum of Solace to World War Z, delivers a film that captures the look and feel of the United Kingdom, or at least some nostalgic version of it. Perpetually overcast skies and a predominance of gray tones saturate the muted color palette achieved by cinematographer Matthias Koenigswieser, which is interrupted by the brightly colored designs of Milne’s fantasy characters. Pooh’s red sweater, Piglet’s pink skin, and Eeyore’s blue fur help remind the protagonist that not everything is numbers, documentation, and presentations to a conference room of stuffy suits. Most convincing, as suggested, is the computer animation that brings Pooh and company to life, while the writers, rather than invent new and memorable sayings, rely on a quote-book of Pooh’s most famous lines, especially “I always get to where I’m going by walking away from where I’ve been” and “People say nothing is impossible, but I do nothing every day.”

The virtue of enjoying life, of doing nothing with loved ones rather than committing oneself to a thankless existence as a workaholic, also recalls the realization of Mr. Banks from Disney’s Mary Poppings or Robin Williams’ middle-aged Peter Pan in Hook, both obvious touchstones for the filmmakers of Christopher Robin. Which is to say, Disney has made another uninspired live-action version of a heartwarming character by relying on derivative ideas, and the result amounts to an unabashed cash-grab dependent on name-brand awareness. Having enjoyed many of Disney’s earlier Winnie the Pooh stories, either based on Milne or capturing the author’s easygoing pleasantness, Christopher Robin comes as a disappointment, as many of their live-action adaptations have. Then again, this is a minority opinion for these hugely successful productions, widely enjoyed by mainstream audiences. But after viewings of either Mary Poppins or Elf, this movie will seem suspiciously familiar.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review