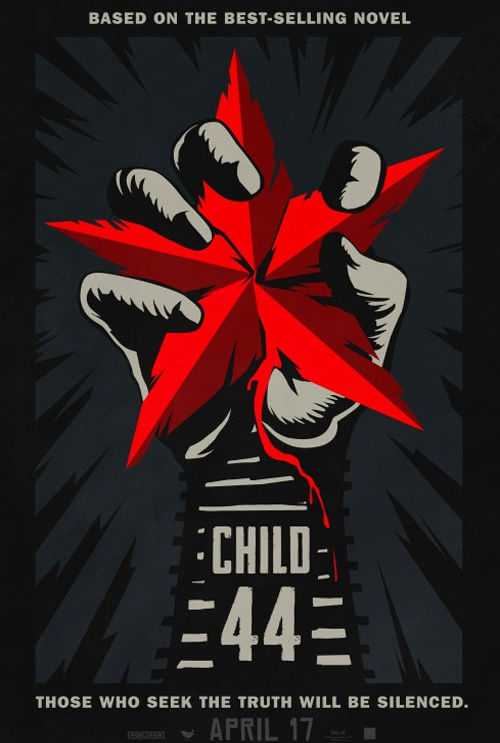

Child 44

By Brian Eggert |

An early scene in Child 44 depicts a political suspect (Jason Clarke) running from his pursuers in Communist Russia. Rather than accept capture, the suspect pleads for death and even violently stabs himself in the stomach to prevent his arrest. Such a fearful atmosphere flourished under Joseph Stalin’s dictatorship, which is the subject of this very Westernized representation of the U.S.S.R. The film was effective enough to rustle feathers, apparently, since the ministry of culture in Moscow banned director Daniel Espinosa’s Soviet-era serial killer drama from playing in Russian cinemas. Minister Vladimir Medinsky accused the Hollywood production of portraying Russia as something akin to a “Mordor” (as in the evil realm from The Lord of the Rings) populated by “physically and mentally inferior subhumans.” Medinsky’s remarks may be inflated, but not completely unfounded.

Based on the 2008 best-seller by Tom Rob Smith, the story borrows the story of real-life Russian serial killer Andrei Chikatilo (whose killings took place between 1978 and 1990) and moves the events to 1953, in a setting of political paranoia, corruption, and desolation. Opening titles remind us of Stalin’s adage, “There is no murder in paradise,” and later, a character argues that murder is “strictly a capitalist disease”. It’s a bleak and hopeless atmosphere, and linking the death of innocent children with the politics of the nation at the time isn’t exactly a subtle indictment. Moreover, the director of actionized thrillers like Easy Money and Safe House hardly seems equipped to deliver a sobering drama involving political oppression and child murder. And with its pointedly non-Slavic cast, Child 44 features an impressive roster of actors delivering muddled Russian accents, leaving us to wonder what Espinosa has against today’s native Russian talents?

Having survived the Holodomor famine in Ukraine in the 1930s, only to become a hero in World War II for the Russian military, Leo Demidov (Tom Hardy, intense as usual) investigates traitors to the regime. Alongside his friend Alexei (Fares Fares) and the sadistic but cowardly Vasili (Joel Kinnaman), Leo knows that “When you are arrested, you are already guilty.” When Alexei’s young son is found dead, clearly murdered, Leo is ordered by his superior, Major Kuzmin (Vincent Cassel), to inform Alexei that the child’s death was an accident. Leo knows that suggesting otherwise would be considered traitorous, and so he follows orders. Eventually, Kuzmin orders Leo to investigate his own wife, Raisa (Noomi Rapace). Knowing that he has no choice but to report her as a traitor, less he too be named guilty, Leo stands alongside his wife. As a result, they’re both arrested and sent to work under General Mikhail Nesterov (Gary Oldman) in Volsk, an industrial town.

Before long, the authorities in Volsk find the body of another boy, and Leo becomes convinced it’s another in part of a series. He persuades Nesterov to launch a clandestine investigation of child murders across Russia, and they eventually discover dozens have been slain in a manner identical to Alexei’s boy. The killer, played by Paddy Considine, is revealed without much ceremony and receives a thin backstory about being abused as a child. But he’s a one-note creature, used in large part to connect a “monster” like a child killer to Vasili, the film’s other “monster,” who represents the absolute level of corruption behind the Iron Curtain. Richard Price’s screenplay uses the word “monster” far too often, which makes Child 44 something of an anti-Soviet propaganda piece.

The plot description above is far more focused than the film itself. Over two hours and seventeen minutes, the story roams between the serial killer, the political conditions, and the complex marriage of Leo and Raisa. None of these strains are fully explored or satisfying, and each reinforces the film’s propagandistic stance. Even the tech package serves to represent Russia as a miserable, hopeless place. Cinematographer Oliver Wood shoots on grainy celluloid, using a grimy color palette to reflect the grueling environment; but the bobbling, shaky camera movements and over-edited shots fail to immerse the audience. Worse, the film meanders and loses itself in distracting subplots as if Espinosa, and his editors Pietro Scalia and Dylan Tichenor, could not decide what to leave in and what to leave on the cutting room floor. A brief sequence about arresting homosexuals as criminals seems present, if only to twist the knife in the film’s indictment of Communist Russia.

This is a drab film, though not one that deserves to be banned. Its narrative is too unfocused, shoddily assembled, and overall too slow-moving to be considered dangerous. Indeed, the Russian ministry of culture overreacted by likening Child 44‘s representation of the U.S.S.R. to the home of Middle Earth’s Dark Lord. Medinsky gives it too much credit; there are far worse aspects about the film than its absolute damnation of an undeniably questionable period in Russian history. Take the melodramatic dialogue, how several actors affect caricature-quality accents or the downright clumsy patchwork achieved by the editors. The entire thing plays like a troubled production, something that has suffered from reshoots and countless versions rejected by audience test screenings. However, the production suffered no such troubles (at least, none that were reported). The problem is that filmmakers have tried to deliver a three-hour-plus story in a much shorter timeframe, and the result is a surface-level examination of a subject that requires far more perspective and probing. What we’re left with is plodding, rushed, and underwhelming on all fronts.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review