Chi-Raq

By Brian Eggert |

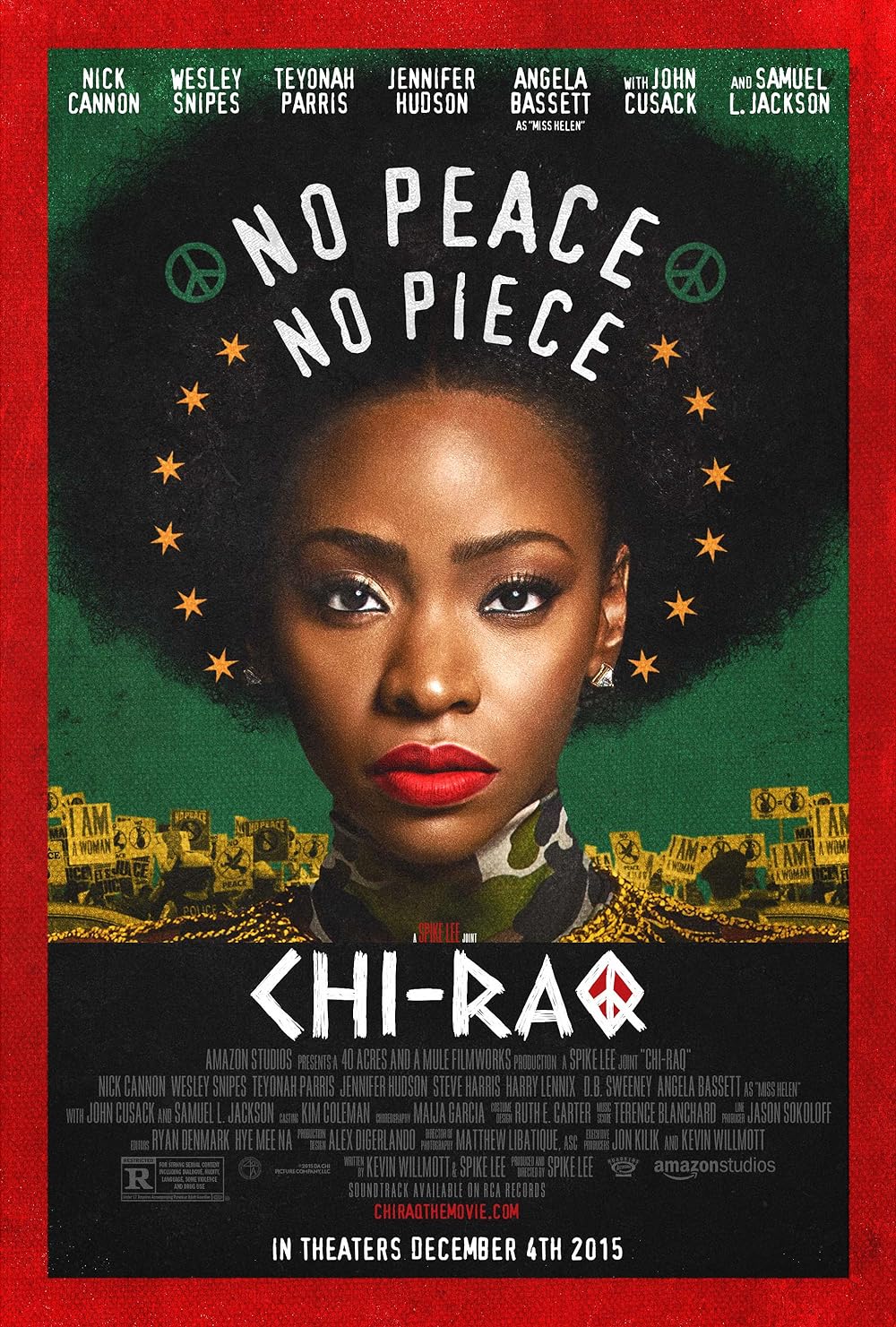

Athenian playwright Aristophanes wrote comic satires long before Shakespeare borrowed from his sense of humor, political commentaries, and use of fantasy. Aristophanes was born in 446 BC and just fifteen years later the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta broke out, lasting until 404 BC. For these formative years in Aristophanes’ life, he knew the horrors of war and bloodshed. Death was all around him. The so-called “Prince of Comedy” wrote about the war in nearly each of his plays, among them Lysistrata, about a woman who seeks to stop the Peloponnesian War by convincing women on both sides of the conflict to lead a nonviolent sex strike. In Chi-Raq, Spike Lee and co-writer Kevin Willmott (director of CSA: The Confederate States of America, from 2004) find a modern-day parallel in Chicago’s South Side, a sump of gang violence, gun-fetishism, and rampant machismo perpetuated by an uncaring system and a community feeding on itself.

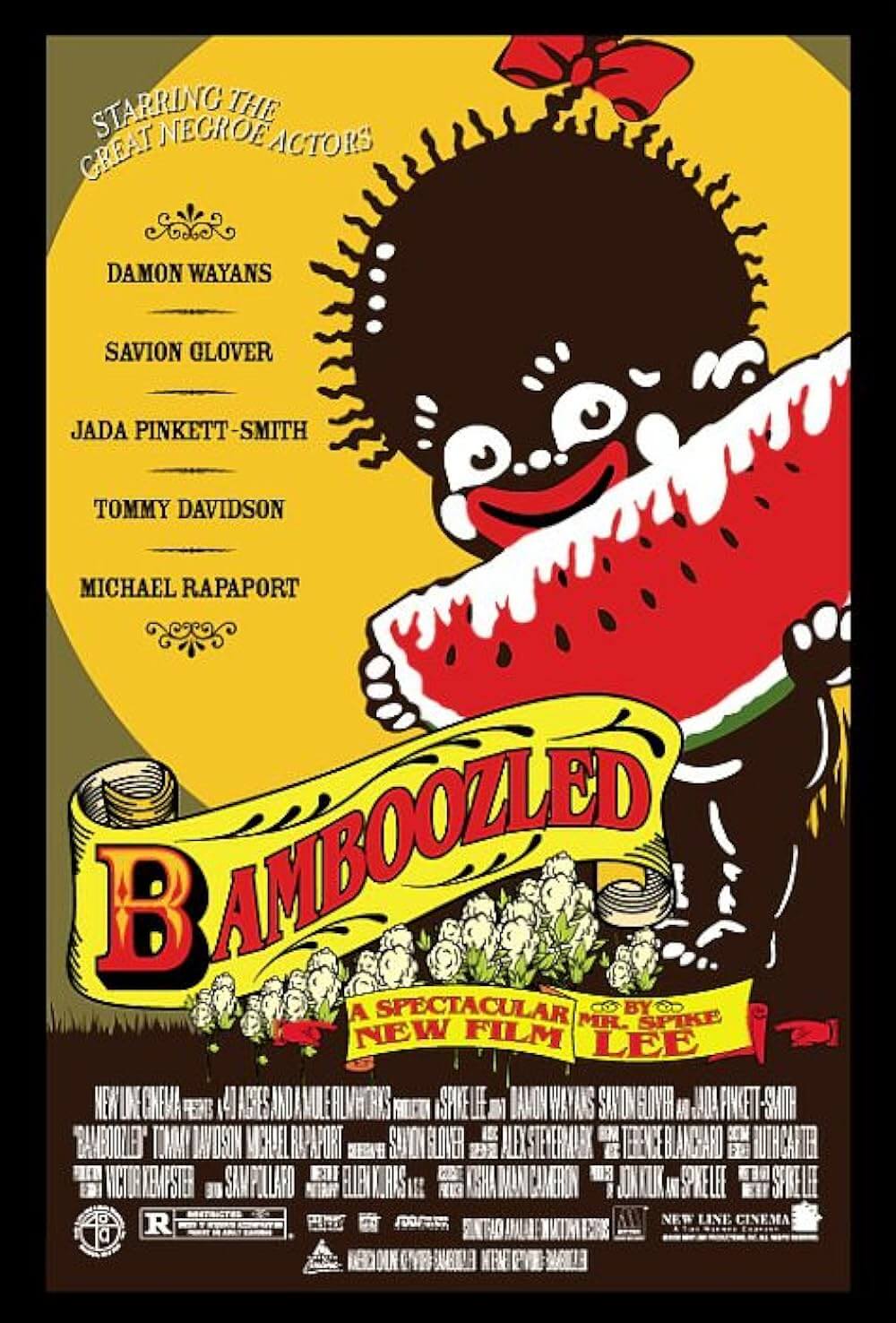

Lee’s most formally engaging and socially minded film since Bamboozled (2000), this polemic satire is also the first feature to be released by Amazon Studios, which has devoted itself to working with important directors on less commercial fare. It’s a timely picture, having debuted in limited release just days after 14 people were gunned down at a San Bernardino holiday banquet. While normally such a ripped-from-the-headlines tragedy might limit the prospect of audiences rushing to see something like Chi-Raq, anger over gun violence in America is a requisite emotion for the film to be fully effective. Elsewhere, Chicago mayor Rahm Emanu has spoken out about his displeasure with the title itself—the term “Chi-Raq” refers to the volume of murders in Chicago outnumbering American casualties in Afghanistan and Iraq combined. But it wouldn’t be a great Spike Lee film if it didn’t make anyone mad.

Lee’s film isn’t just about Chicago; it’s about cities like Philadelphia, Baltimore, and New York, where gun violence runs rampant. Lee’s didactic argument throughout seems to be that the U.S. government spends hundreds of millions to rebuild Middle Eastern countries, and yet a veritable war zone is being ignored on American soil. Whether it’s because there’s a vested interest (black gold) in overseas politics or simply because it’s a racist state, Lee’s anger over the situation becomes beautifully constructed artistry in Chi-Raq. The film opens with red letters on a black screen, the lyrics to “Pray 4 My City” in an overture performed by Nick Cannon, also one of the film’s stars. Then a siren fills the audience’s ears and the words “This is an Emergency” flash on the screen. The formal audaciousness doesn’t end there, not by a long shot.

Enter Dolmedes (Samuel L. Jackson), the film’s one-man Greek chorus whose name is either a water spider or a nod to Dolemite (a stretch). Breaking the fourth wall, Dolmedes speaks directly to the audience and gives a refresher course on the method of Greek plays employed throughout the film, specifically that characters speak to each other in rhyming verse. Bombastic as ever, Jackson sketches out a conflict between two Chicago street gangs, the purple-wearing Trojans, led by Cannon’s self-named character Chi-Raq, and the orange-garbed Spartans, led by giggling ganglord Cyclops (Wesley Snipes, behind a bedazzled eye patch). Their conflict doesn’t take place in Athens, of course, but modern-day Englewood, Chicago, where gang violence has led to the death of a young girl named Patti, whose mother (Kate Hudson) wants justice. But everyone in Englewood is too afraid to speak up for fear of gang retaliation. Terence Blanchard, Lee’s longtime collaborator, provides a score whose sobering effect is absolute in these scenes.

Enter Dolmedes (Samuel L. Jackson), the film’s one-man Greek chorus whose name is either a water spider or a nod to Dolemite (a stretch). Breaking the fourth wall, Dolmedes speaks directly to the audience and gives a refresher course on the method of Greek plays employed throughout the film, specifically that characters speak to each other in rhyming verse. Bombastic as ever, Jackson sketches out a conflict between two Chicago street gangs, the purple-wearing Trojans, led by Cannon’s self-named character Chi-Raq, and the orange-garbed Spartans, led by giggling ganglord Cyclops (Wesley Snipes, behind a bedazzled eye patch). Their conflict doesn’t take place in Athens, of course, but modern-day Englewood, Chicago, where gang violence has led to the death of a young girl named Patti, whose mother (Kate Hudson) wants justice. But everyone in Englewood is too afraid to speak up for fear of gang retaliation. Terence Blanchard, Lee’s longtime collaborator, provides a score whose sobering effect is absolute in these scenes.

Meanwhile, Chi-Raq’s beautiful lover Lysistrata (Teyonah Parris) wants to see the killing stop as well. After receiving an impassioned call to action by her peaceful neighbor, Miss Helen (Angela Bassett), Lysistrata mobilizes women on both the Trojan and Spartan sides of the conflict. “No peace, no pussy” is their motto, and it’s a slogan that catches on worldwide. Women everywhere begin to carry signage and close their legs in protest to violence. At first, the gangs’ men think it’s a joke, but soon enough they’re being driven out of their minds. Some simply go stark raving mad, while others (including a men’s club headed by Steve Harris) lead an “anti-blue balls” counter-campaign. An outlandish D.B. Sweeny plays Chicago’s mayor, who sicks the Chicago police after Lysistrata once she occupies a local armory, formerly run by a Confederate flag-waving nut, General King Kong (David Patrick Kelly). The prolonged stand-off eventually comes down to a brass-bed sex-off between Chi-Raq and Lysistrata.

The details about how Lysistrata manages to convince prostitutes, porn sites, and even phone sex operators (There are still phone sex lines?) to set aside their occupations in favor of peace are never explained. After all, Lee fully embraces Aristophanes’ style of comic fantasy with a wildly funny degree of satire that will win no supporters among devout realists, or viewers lacking a sense of humor. If there’s a finer point about Chi-Raq to be made, look no further than a hoarse-voiced John Cusack as Father Mike Corridan, inspired by the real-life priest and social activist Michael Pfleger. During Patti’s funeral, Corridan delivers a fiery speech about his disgust that violence is admired by the youth, politicians being in the pockets of the NRA, governmental disregard for lower-income neighborhoods, and the high percentage of African Americans in the country’s prisons. A viewer can’t help but want to applaud when it’s over.

Women throughout history have successfully used sex strikes to rally for peace. Leymah Gbowee is cited within Chi-Raq as Lysistrata’s inspiration. Gbowee is a Nobel Peace Prize laureate and organizer of the Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace in 2003. You’d have to be foolish and blind to the satire’s true intent to believe Lee is really expecting such a wild concept to work in Chicago, or the world over (however, there is a certain mad logic here). Lee famously constructs interpretable, unorganized arguments within a flurry of mixed messages and perspectives, all represented at the same time, working opposite or parallel to one another. His filmic statements are sometimes difficult to discern, but his anger over the situation is palpable. Bamboozled is an ideal example of this, ironically being about how satire loses its power when the crowd misinterprets its meaning. Chi-Raq might be called uneven, but that’s Lee’s sometimes imprecise and post-modern method; he represents multiple points of view at once and allows the audience to discuss afterward.

Women throughout history have successfully used sex strikes to rally for peace. Leymah Gbowee is cited within Chi-Raq as Lysistrata’s inspiration. Gbowee is a Nobel Peace Prize laureate and organizer of the Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace in 2003. You’d have to be foolish and blind to the satire’s true intent to believe Lee is really expecting such a wild concept to work in Chicago, or the world over (however, there is a certain mad logic here). Lee famously constructs interpretable, unorganized arguments within a flurry of mixed messages and perspectives, all represented at the same time, working opposite or parallel to one another. His filmic statements are sometimes difficult to discern, but his anger over the situation is palpable. Bamboozled is an ideal example of this, ironically being about how satire loses its power when the crowd misinterprets its meaning. Chi-Raq might be called uneven, but that’s Lee’s sometimes imprecise and post-modern method; he represents multiple points of view at once and allows the audience to discuss afterward.

Any discussion of Chi-Raq—and there will be many of them—must consider the whirlwind of formal audacity that Lee assembles here. Aside from nods to Aristophanes’ play, the director references Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove in the scenes with General King Kong, and he ends the film with Dolmedes standing on the bottom of the screen before an American flag, recalling George C. Scott in Patton. When Dolmedes appears, sometimes everything behind him freezes so he can speak, whereas sometimes he interacts with characters onscreen. Texts flash before us in pink pop-ups. Lee saturates his gangland environments with posters for “Da Bomb”—the director’s fake malt liquor brand that has made appearances in several of his films. Characters frequently burst into dance or song, including a male vs. female standoff evoking West Side Story. There are no formal rules in Lee’s film, self-imposed or otherwise, and that leaves Chi-Raq a fascinating and unforgettable viewing experience.

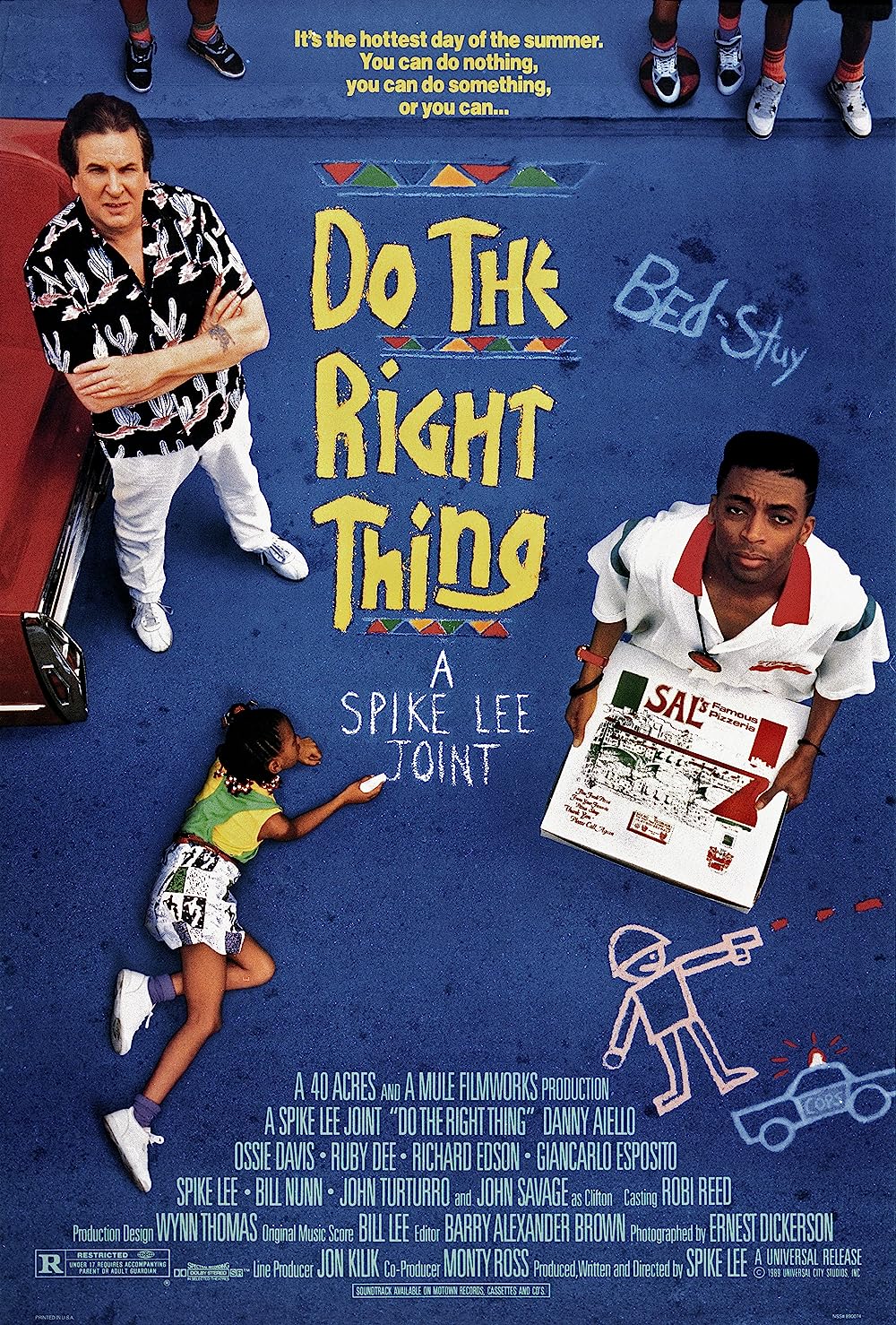

The tonal shifts from broad satire to devastatingly emotional scenes of loss may prove too drastic for some. But Lee has something profound to say, as he often does. Boiling the material down to a single message or two proves difficult; however, Miss Helen’s charge to “Be a good man” seems appropriate, along with Lee’s final titles that read “Wake Up!” Decked out in colorful garb by costumer Ruth E. Carter and performing in a range of styles, Lee’s cast is exceptional, especially Parris. Overall, Chi-Raq explodes onto the screen with an undeniable vitality and timeliness, preaching its potent message in a sexy, saddening, offensive, and certainly divisive way that only Spike Lee could. Those versed in his cinema will welcome Chi-Raq after his recent, underwhelming titles like Da Sweet Blood of Jesus and his remake Oldboy. It’s one of Lee’s most accomplished and effective films in years, putting it among Bamboozled, Do the Right Thing, Malcolm X, and 25th Hour as one of his most thought-provoking works.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review