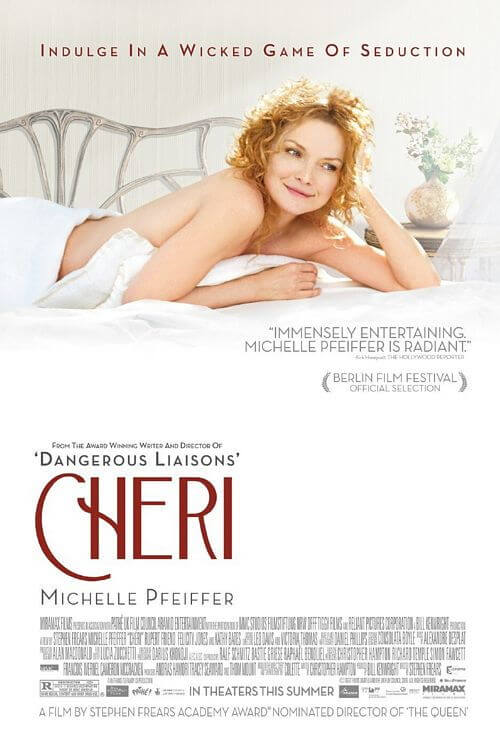

Chéri

By Brian Eggert |

Michelle Pfeiffer’s role in Chéri demonstrates how well she’s aged, not only in the physical sense, which is true enough but also in the sense that she adapts with her roles appropriately. In other words, she acts her age, which conveniently enough is exactly what this film is about. She commands her characters with the same confidence and intelligence now that she did twenty years ago, except her characters are getting older and reflecting upon their age. Like Pfeiffer, they’re taking it rather well.

Based on the 1920s books Chéri and La Fin de Chéri by French novelist Collette, herself a controversial figure and openly sexual being, here’s another film by director Stephen Frears (The Queen) that sparkles with sumptuousness and class. It’s a lush production relying mostly on the acting wiles of Pfeiffer, who reteams with Frears after Dangerous Liaisons in 1988. Pfeiffer tests her offscreen persona in a role that, by the end, suggests her sex appeal won’t last forever. But it’s a role that displays her aptitude for playing intelligent, complicated women (see The Age of Innocence). And instead of praising cougars as so many films do nowadays, it portends that such a relationship can be damaging for both parties, particularly when love is involved.

Sometimes not acting one’s age is the perfect thing to do; other times, it’s the worst possible solution. For a middle-aged French courtesan at the turn of the last century, it’s the only thing to do. Léa de Lonval (Pfeiffer) has worked as a high-class prostitute for her entire life, so appearing young and sexually available is part of her profession. She and those like her are part of a noble class of lovers-for-hire to royalty and wealthy businessmen, and they receive obscene amounts of money for their bedroom antics. Léa, for example, keeps homes in Paris and a summer “cottage” (mansion) in Normandy.

When the story opens, Léa has passed her prime, and she’s beginning to know it. She’s even at the risk of becoming like Madame Peloux (the delightful Kathy Bates), a retired courtesan wealthy beyond compare and now fat with the plunder of working on her back, as her impressive country chateau indicates. Madame Peloux’s spoiled son, Fred (Rupert Friend), whom Léa has called Chéri since he was a boy, lingers around his mother’s home, sleeping into the afternoon to fuel his nightly escapades. Léa and Chéri have a strange relationship; she presides over him like some parental force but also a sexual one. All at once, they begin a six-year love affair that works to keep both of them younger than they have any right to be, and that affair ends abruptly when Madame Peloux arranges a marriage for her son.

The pouty and flamboyant Chéri goes along with the marriage, though Léa refuses to be a mistress for his married life. Apart, they seem tortured: Léa finally realizes her age is a weakness, and Chéri, though faithful to his new wife, is bored and certainly not in love. The screenplay by Christopher Hampton (Atonement) dawdles here and there, keeping us yearning for those moments when Bates and Pfeiffer verbally spar, or when Léa and Chéri engage in their, at times, absurd romance. The last act of the film meanders the most, as Chéri breaks in his new wife, and Léa deludes herself with a young male concession. Even at well under two hours, the sequence of events might be tighter and more focused on Léa, Chéri, and Madame Peloux, since those are the only characters worth exploring.

Frears, however, makes Pfeiffer his brilliant centerpiece, and her performance is something to admire. Consider Pfeiffer’s last several roles because, in each, her characters reflect and dwell on age. If she’s the evil witch Lamia from Stardust, she’s willing to curse or kill anyone to retain her failed youth and dwindling beauty. If she’s Rosie in I Could Never Be Your Woman, she finds that love and attraction transcend age, and she realizes that is liberating. In Chéri, the sad outcome of the story moves from fateful romance to timeworn tragedy, and Pfeiffer never fails to commit to her role and all the pains therein. It’s an exceptional performance, and along with the ever-relevant themes about age and beauty, it makes the film worth seeing.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review