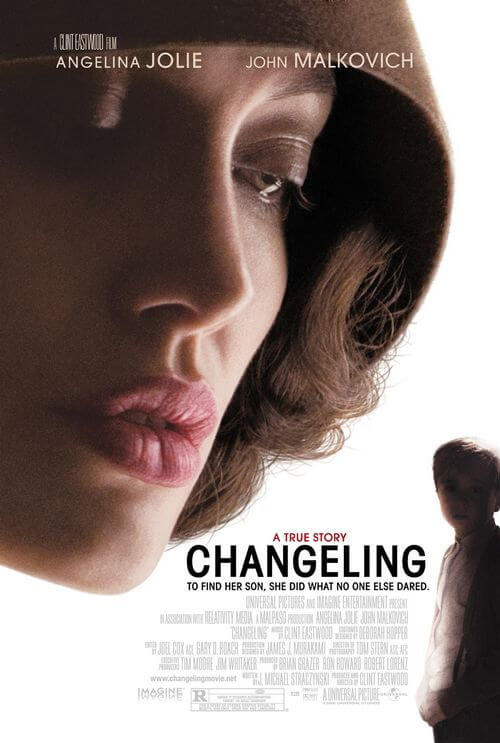

Changeling

By Brian Eggert |

Clint Eastwood’s Changeling contains enough genres to send the viewer into frenzied confusion over which direction they’re going. It begins with the melodramatic search for a lost child, twists into a police corruption yarn, nods at a serial killer thriller, makes a brief pit stop in an insane asylum, embraces courtroom drama with two intercut courtroom scenes, and then ends with a whimper. And while the result might occupy too many story types and offer little payoff, somehow Eastwood’s direction, attention to detail, and quiet sophistication dissolve the problems with the muddled structure and make it all worth while.

Set in the late 1920s, the story opens with Christine Collins (Angelina Jolie), a single mother happily raising her nine-year-old son Walter (Gattlin Griffith). Upon returning home from work one day, she finds Walter is missing. The police refuse to file a report for the standard 24 hours. There’s no sign of his whereabouts until six months later when detectives in charge of her case claim they’ve found her boy. She arrives at the train station hopeful, press all around her, the insistent Captain Jones (Jeffrey Donovan) reminding her to tell the public what a fine job the LAPD has done in recovering her child. One problem: The boy they’ve brought isn’t Christine’s son.

“Take him home on a trial basis,” advises Capt. Jones, explaining Christine must be mistaken, that the boy has changed from his ordeal, and she’s likely in shock. Bullied into doing so, she quickly realizes the boy cannot be Walter—the replacement is circumcised and several inches shorter in height. His dentist and teachers maintain they’ve never seen him. And yet, the boy insists he’s Walter. When Christine makes clear that the LAPD has made a mistake, they label her insane, and after publicly announcing it’s not her son, she’s thrown in a mental institution to quiet her protests. Meanwhile, Reverend Gustav Briegleb (John Malkovich) does everything in his power to defend Christine, setting his sights on the notoriously corrupt LAPD.

In a parallel plotline, Detective Lester Ybarra (Michael Kelly, from 2004’s Dawn of the Dead) is sent to a country ranch to find a juvenile for deportation back to Canada. What he finds is the homestead of vicious child murderer Gordon Northcott, creepily portrayed by Jason Butler Harner. The murderer is gone, but he finds the man’s fifteen-year-old cousin, who confesses to something horrible, which in turn leads to several more horrible discoveries and, ultimately, a grim conclusion seen coming long before this picture is anywhere near over.

Production designer James J. Murakami, whose work includes HBO’s Deadwood and several other Eastwood pictures, recreates a world where we believe every surface exists within its period. From Model Ts to Deborah Hopper’s flawless costume design, from fedoras and trenchcoats to discussions surrounding It Happened One Night—the film’s missteps in plot are reaffirmed by the sound verisimilitude. Bounding back into her Girl, Interrupted mode, Jolie does plenty of shouting and teary pleading, her performance appropriately active without straining our tolerance for her showboating. Malkovich muddles through another odd accent. Kelly makes a noble hero. Surpassing these others is the little-known actor Jason Butler Harner, whose tour-de-force portrayal is haunting. He’s carted around in cuffs, his body wobbly as if drunk, always a half-smile cracked on his face; flashbacks show another creature entirely, shouting and howling with blood splattered on his face. The performance is uncanny.

Eastwood’s last few years behind the camera have brought a wealth of unexpected class to the screen, with Mystic River, Letters from Iwo Jima, and Best Picture winners Million Dollar Baby and Unforgiven. Each of these examples takes unconventional turns within standard genres, reaching emotional summits few other filmmakers could manage with his temperance and resolve. Made with patience and delicacy, his films creep up and overtake you from unseen pathways. These shifts never feel forced but rather like natural, if unforeseen, progressions.

Changeling is the showiest of Eastwood’s recent string of affecting productions, almost as if the presence of his Academy Award-winning star and his own attendance behind the camera assured the picture an Oscar or two. Certainly Universal thought the combination would be winning, having released the film in that fourth quarter arena with other award-worthy contenders. Who wouldn’t, with Jolie shouting, “I want my son back,” and bursting into tears every few moments? But as obvious as this “Based on a True Story” ploy might be to earn some easy-as-pie esteem, you’d have to carry a heart of stone in that chest cavity of yours to not find yourself affected by Jolie’s performance, and the connected harrowing tale. Transparent or not, Changeling is an expertly made human drama featuring a stirring combination of Eastwood’s signature low-key tone with some surprising shocks. Overall, the result doesn’t allow for emotional closure and won’t leave audiences with any lasting impressions beyond an appreciation for the production design, but enough about it works to easily recommend.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review