Certain Women

By Brian Eggert |

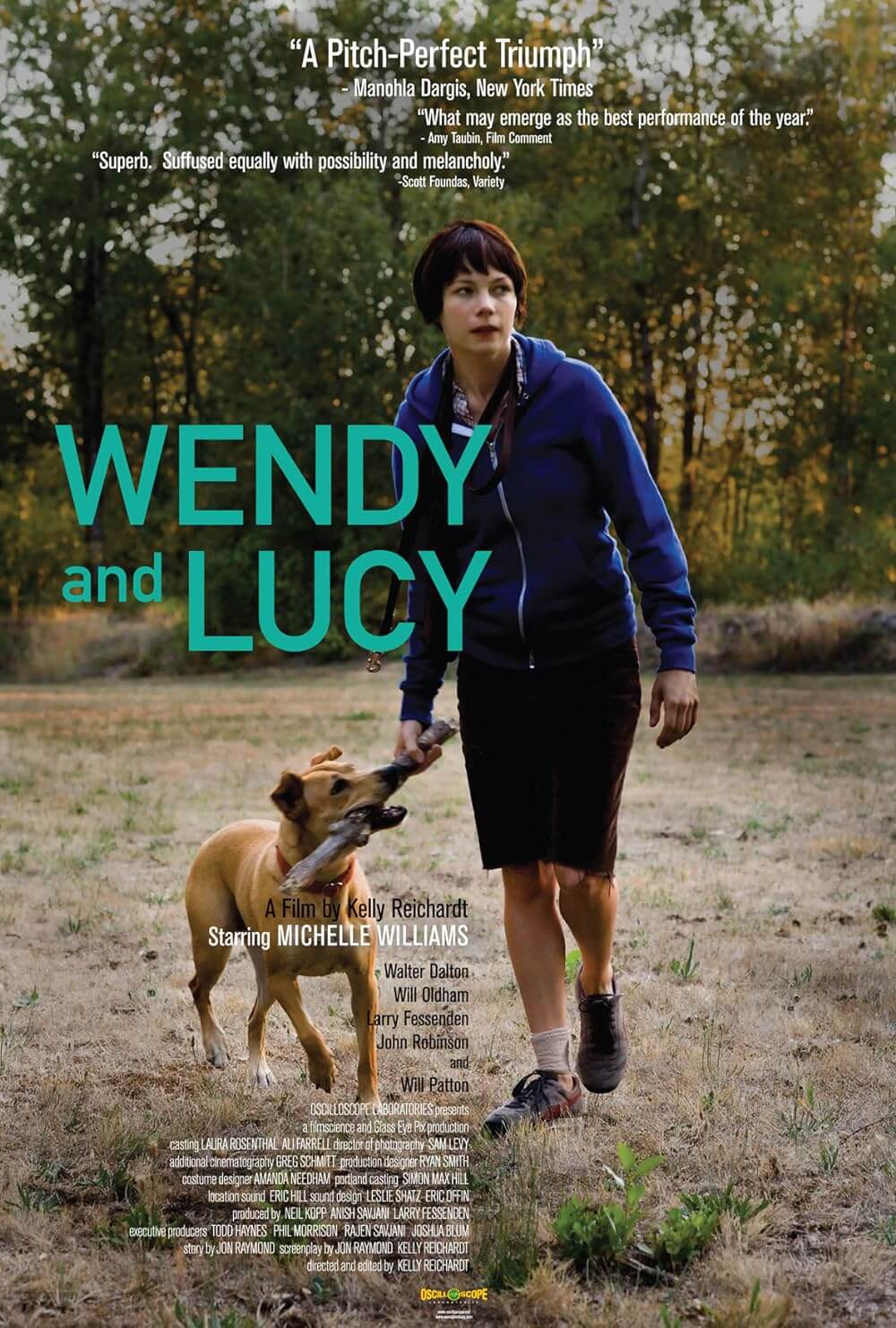

In the opening shot of Kelly Reichardt’s Certain Women, a train moves through an expansive landscape, a vista with Montana mountains under overcast early winter skies. As the train passes on the bottom right corner of the frame, the larger world next to the railroad track remains stationary and unnoticed by the locomotive. The train, a foundational component to cinema from The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station (1895) to Snowpiercer (2013), drives so many films with its inherent forward momentum that it could be a metaphor for mainstream cinema itself. But Reichardt’s 2016 film is less concerned with the train than the stories it passes by without regard or interest. Her screenplay was based on three short stories by Montana-based writer Maile Meloy, and the resulting triptych concerns lives and moments among women that the usual cinematic train would pass by without notice. Reichardt films tend to center on characters that might not otherwise be the subject of a motion picture; it’s the quality that sets her work apart as defiantly independent. It’s no coincidence that Certain Women is dedicated to Reichardt’s dog Lucy, the costar of her 2008 film Wendy and Lucy, which ended with Michelle Williams giving her dog up for adoption and slipping out of town on a train. Watching Certain Women, one cannot help but wonder if Wendy is shivering inside one of those train cars.

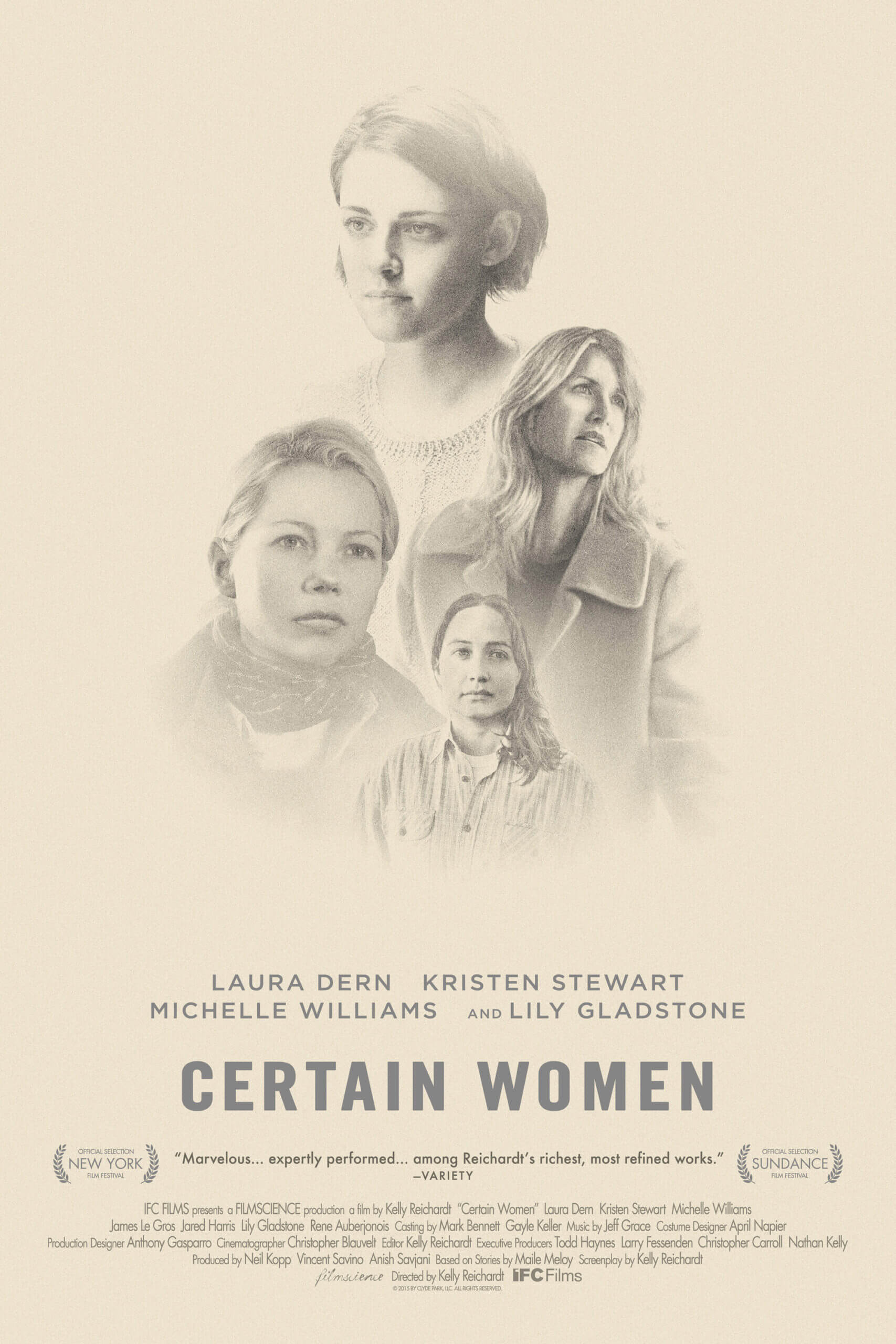

Like Reichardt’s other films, Certain Women moves at a measured (some would say “slow”) pace, exploring the unceremonious lives of its main characters. Given its structure, it’s tempting to call Certain Women an anthology film, except Reichardt, once again serving as her own editor, cuts with sudden, unannounced transitions between stories. There are no titles that declare the movement from one story to the next, and some of the lives on display overlap with one another, so it doesn’t feel like other anthology films we’ve seen. Instead, it feels like a mosaic, although not in the Altman-esque sense of that word. Perhaps a more appropriate comparison is one of melodic variation, where this single piece contains several variations on a theme. To be sure, despite this segmentation into three stories, the film feels like a singular arrangement under Reichardt’s direction; her consistency of tone and theme separates into three stanzas, each a necessary component in a larger structure. They each occupy a similar overarching idea, a snapshot of women’s lives—though, the events, muted as they may seem, should not be described as everyday occurrences. Reichardt doesn’t give undue dramatic importance to moments that would be heightened by another filmmaker. She embraces how quickly the flow of life returns, no matter what kind of ebbs we face along the way.

Certain Women is also Reichardt’s first film since her debut River of Grass (1994) not co-written or based on previously published material by Jonathan Raymond. Though the author of her source material has changed, her concerns as an auteur have not. She evidently chose Meloy’s short stories because they, like Reichardt’s other films, involve characters stuck on the fringes of society, unable to escape their situation. They’re watching the train pass by, as opposed to hitching a ride. The Montana setting also resembles, in its way, the usual Pacific Northwest locations of Reichardt’s other work. Although, the wintry exteriors feel far less lush than the Oregon forests in Old Joy (2006) and Night Moves (2013), and less cinematic than the Western vistas in Meek’s Cutoff (2010). Cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt, who has collaborated with Reichardt for the last decade, drains the color from each image, leaving subdued earth tones outside and a combination of bland colors inside—taupe walls, tan clothes, beige décor. It’s a flat, often visibly grainy, simple presentation that underscores the stifling world these women inhabit.

The first story follows Laura Wells (Laura Dern), a lawyer in Livingston who has just had sex with a married man, Ryan Lewis (James LeGros), on her lunch break. When she returns to work, she finds a client, Fuller (Jared Harris), waiting for her. She has spent the last eight months explaining that, because Fuller has already settled with his company after an accident left him nearly blind, he’s unable to sue again even though the condition has worsened. It takes Fuller getting a second opinion from a male attorney to believe Wells’ legal advice. His next course of action is to get a gun and break into the company’s offices to prove his case, resulting in a hostage situation overseen by a calm-as-can-be cop (John Getz). Regardless of how cinematic a hostage crisis may seem, Reichardt’s attention remains on Wells, who helps convince Fuller to turn himself over to the police, and then returns to the usual tempo of her life. At her core, she’s a woman who, at the end of the day, unwinds on the couch and curls her bare toes against her snoozing dog’s fur, adaptable and even stoic to whatever the world has in store.

The first story follows Laura Wells (Laura Dern), a lawyer in Livingston who has just had sex with a married man, Ryan Lewis (James LeGros), on her lunch break. When she returns to work, she finds a client, Fuller (Jared Harris), waiting for her. She has spent the last eight months explaining that, because Fuller has already settled with his company after an accident left him nearly blind, he’s unable to sue again even though the condition has worsened. It takes Fuller getting a second opinion from a male attorney to believe Wells’ legal advice. His next course of action is to get a gun and break into the company’s offices to prove his case, resulting in a hostage situation overseen by a calm-as-can-be cop (John Getz). Regardless of how cinematic a hostage crisis may seem, Reichardt’s attention remains on Wells, who helps convince Fuller to turn himself over to the police, and then returns to the usual tempo of her life. At her core, she’s a woman who, at the end of the day, unwinds on the couch and curls her bare toes against her snoozing dog’s fur, adaptable and even stoic to whatever the world has in store.

Reichardt cuts to the second story as if it were the next morning. We find Gina Lewis (Michelle Williams) walking through woods near the site of her new home, where she has camped for the night along with her husband, Ryan (yes, that Ryan) and teenage daughter Guthrie (Sara Rodier). Gina is responsible, demanding, and sure of her vision for the eventual house, though she remains an outsider in her own family, ever excluded from the in-jokes and good humor shared between her husband and daughter. The bulk of the story entails Gina and Ryan asking an older friend, Albert (René Auberjonois), if they can buy the sandstone bricks piled in Albert’s yard. Gina wants Ryan to ask because “he trusts you” and “you know how to talk to him,” and anyway, Albert seems to resent Gina’s role and talks only to Ryan. “Your wife works for you,” he says to Ryan. “No, she’s the boss, actually,” Ryan responds. But not unlike her husband and daughter, Albert resents her control. It’s quietly tragic that Gina is judged for the way she approaches getting what she wants from Albert. It’s a feeling articulated after Albert’s brief exchange with her, where he points out that a quail’s call sounds like “How are you?” and mimics the chirped reply. When the family comes to pick up the sandstone, Gina waves at Albert inside, the quail’s question calling out in the distance behind her. Reichardt doesn’t include the bird’s reply, nor does Albert answer her waive. On its surface, this might be the most undramatic and least pointed of the three stories in Certain Women, until we remember that her husband spent a recent afternoon with Laura.

The final story, by contrast, is the most resounding in its emotional ache and most complete in its dramatic arc. An unnamed rancher, played by Lily Gladstone, goes through the stale routine of tending to horses, feeding the resident Corgi, and watching television. One night, she drives into town and sees a few cars gathered at the local school, and with nothing better to do, she decides to check it out. Inside, a young law graduate, Beth Travis (Kristen Stewart), has driven four hours to teach a course on school law for which she is woefully unprepared. Nevertheless, after class, Beth asks the rancher if there’s somewhere in town to eat, and they sit down for a meal, making an easy connection over small talk. With Beth arriving on Tuesdays and Thursdays, the rancher’s days in-between resume their usual cycle, before she feels alive once more in Beth’s presence. One day after class, she offers Beth a ride on a horse to the diner, and the two share a silent amble. The rancher’s yearning for company is almost palpable; as for Beth, her presence and desire are more illusive—demonstrated when the rancher drops Beth off at her car and takes hold of her scarf as an intimate gesture. Beth indiscriminately pulls it away and says goodbye. When Beth does not show for the next class, the rancher makes a desperate drive to Livingston only to face her rejection in the form of a crushing non-response. It’s a story that ends with a perfect metaphor for the rancher’s heartsick detour from the banal rhythm of her humdrum days.

The connections between these stories, however tenuous—Laura sleeping with Gina’s husband, or the rancher looking for Beth at Laura’s law office—force one to consider why Reichardt chose these three Meloy stories over all others. Each is about a woman overlooked or ignored because of her gender, whether it relates to her occupation, role in the family, or romantic interest. At the same time, Reichardt, ever following the influence of Robert Bresson and Yasujiro Ozu with her work, once more explores the inner lives of her characters, the restrained drama found in everyday life. The stories do not offer finality or a clear outcome for any of the characters; there’s an uncertainty about where they will end up and how the events depicted will shape their lives, though it’s doubtful they will at all. Rather, Reichardt demonstrates her continued interest in characters who plug along, having surrendered to the weary aspects and patterns of their lives. Though the film contains the potential of heightened dramatics in its stories about a hostage situation, an ambitious woman, and unrequited love, Reichardt finds the root of her characters in quieter moments: a long shot of Dern walking around a mall alone; Williams taking a morning walk by a stream, dreaming of what her house will look like; Gladstone going through the ranch’s routine, dropping hay and brushing horses. There’s more said about these characters in scenes that feel removed from the patterns of traditional cinematic drama than those of higher stakes.

The connections between these stories, however tenuous—Laura sleeping with Gina’s husband, or the rancher looking for Beth at Laura’s law office—force one to consider why Reichardt chose these three Meloy stories over all others. Each is about a woman overlooked or ignored because of her gender, whether it relates to her occupation, role in the family, or romantic interest. At the same time, Reichardt, ever following the influence of Robert Bresson and Yasujiro Ozu with her work, once more explores the inner lives of her characters, the restrained drama found in everyday life. The stories do not offer finality or a clear outcome for any of the characters; there’s an uncertainty about where they will end up and how the events depicted will shape their lives, though it’s doubtful they will at all. Rather, Reichardt demonstrates her continued interest in characters who plug along, having surrendered to the weary aspects and patterns of their lives. Though the film contains the potential of heightened dramatics in its stories about a hostage situation, an ambitious woman, and unrequited love, Reichardt finds the root of her characters in quieter moments: a long shot of Dern walking around a mall alone; Williams taking a morning walk by a stream, dreaming of what her house will look like; Gladstone going through the ranch’s routine, dropping hay and brushing horses. There’s more said about these characters in scenes that feel removed from the patterns of traditional cinematic drama than those of higher stakes.

As with all Reichardt films, Certain Women is not about characters who pass through obstacles; rather, they remain trapped within them, in a state of limbo, or in these stories, serving others. In a final coda, Reichardt returns to each of the three main characters and finds them serving food—Laura brings Fuller a vanilla shake, Gina serves burgers to her family, and the rancher supplies the horses with feed. Whatever their experiences, the requirements of daily life persist. There is no closure as life carries on, and Reichardt doesn’t offer it here. And within such constrained tension, the second story emerges as the most powerful, even though the first one about a hostage situation and the third about a never-to-be romance align better with conventional short stories. Gina’s episode is the one that demands the most consideration, in part because Williams’ performance is impenetrable, in part because it feels in sync with Reichardt’s unassuming realism. More than the others, it reveals how Certain Women is a portrait of life that does not move with the unstoppable momentum of a locomotive, with set departures and arrivals. Instead, life is something to be patiently observed and appreciated in all of its unpretentious detail.

Bibliography:

Fusco, Katherine, and Nicole Seymour. Kelly Reichardt – Contemporary Film Directors. University of Illinois Press, 2017.

Hall, E. Dawn. ReFocus: The Films of Kelly Reichardt. Edinburgh University Press, 2018.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review