Censor

By Brian Eggert |

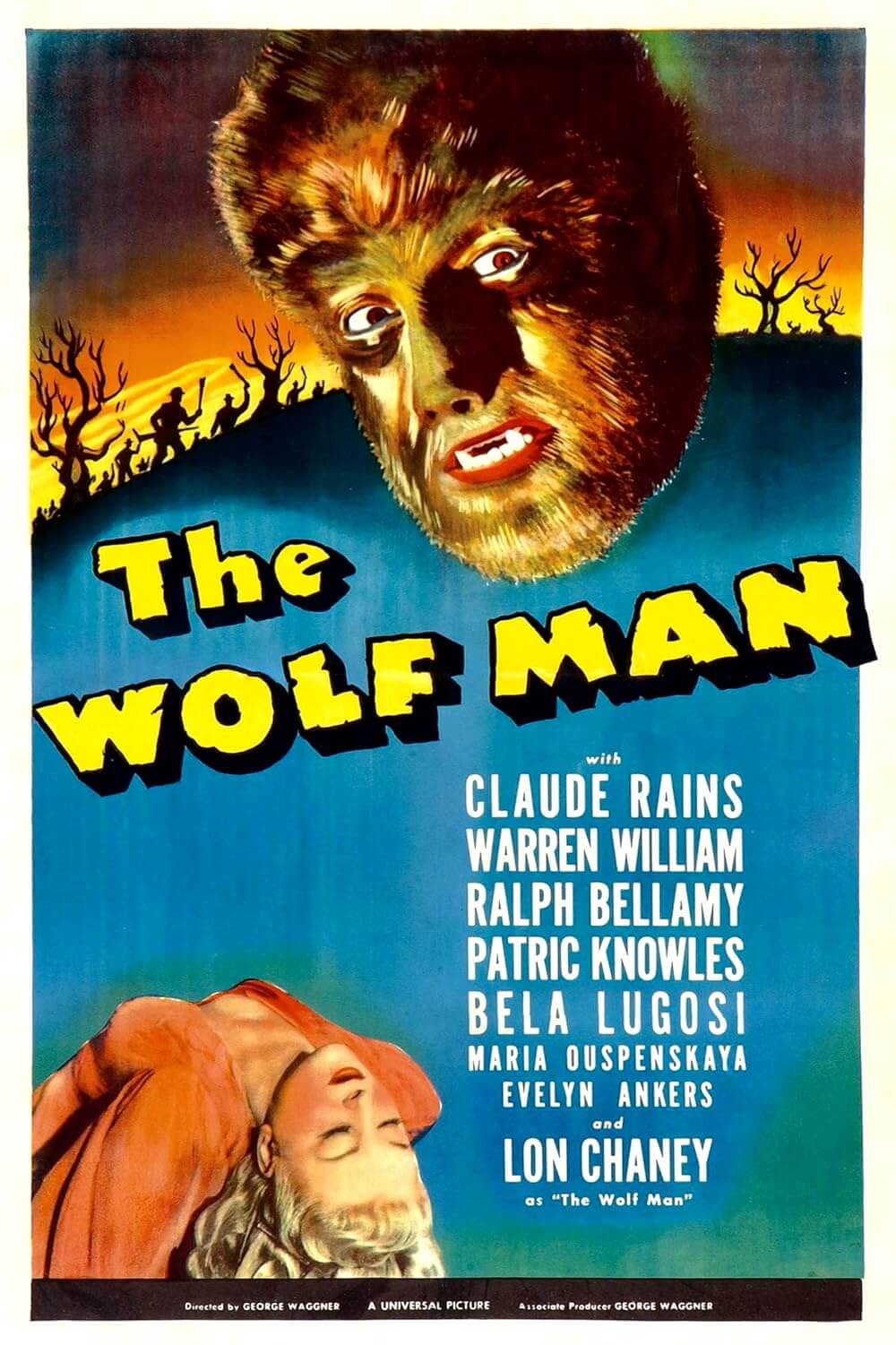

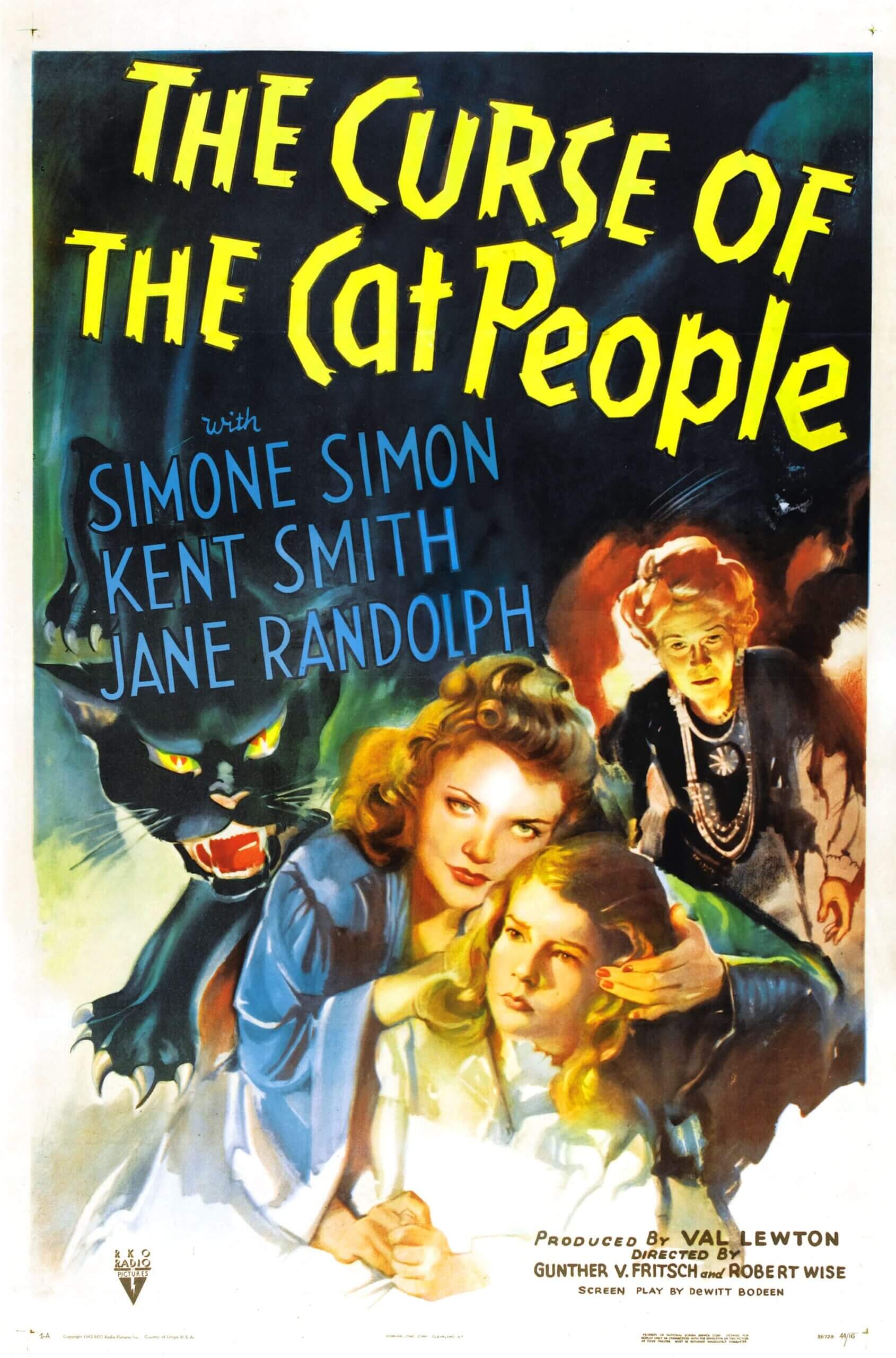

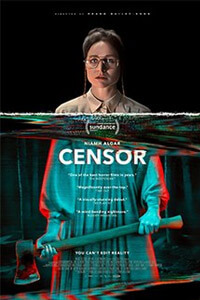

Video Nasties and the moral panic fuelled by the UK’s tabloid media typify Thatcher-era conservatism for cinephiles. In the early 1980s, public and political outcries claimed that horror and exploitation films would corrupt the minds of those exposed and should, therefore, be trimmed of their taboo scenes or altogether banned. The Video Recordings Act of 1984 sought to create a system in which the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) would review and potentially edit out graphic content, making it safe for public consumption. The system backfired. Protests against Thatcher’s restrictions spilled into the street. At the same time, censorship birthed a cult demand for inaccessible titles on video cassettes deemed forbidden or obscene, including Cannibal Holocaust (1980), I Spit on Your Grave (1978), and dozens more. Copies could be seized and destroyed, and distributors of these illicit tapes could be persecuted, making them even more coveted. Using this era as a backdrop, Censor is a moody, leisurely paced British horror film that diagnoses why a woman who works for the censorship board suddenly finds herself haunted by yet drawn to images of violence.

The pale and repressed Enid (Niamh Algar) spends her days watching graphic movies and making notes to herself like “Eye gouging must go!” She believes her latest movie, an Evil Dead-inspired hunk of schlock where an unseen force torments a woman in the woods, is “dangerous” to society. But Enid is the real danger. She seems unstable and bound inside, evidenced in a tense meal with her parents. They need to find closure after a years-old trauma, so they present Enid with a death certificate for her sister, Nina, who vanished at age 7. “You’ve never been clear about what happened,” they remind Enid, who claims her sister must still be alive out there, somewhere. The pressure grows after the public learns that she approved the 1974 slasher Deranged, a real movie about an Ed Gein-style necrophile killer, and someone supposedly copied its face-eating scene. Enid begins to lose her grip when she watches a new (fictional) film, called Don’t Go in the Church, and experiences hallucinations of the woods where her sister went missing years earlier.

Director Prano Bailey-Bond, who co-wrote the screenplay with Anthony Fletcher, nods to the banned B-movies of yesteryear while employing a severe aesthetic. Annika Summerson’s cinematography is cold and drained of color with symmetrical angles that capture Enid’s ordered universe. Note how the filmmakers contain Enid in drab interiors, from the BBFC office directly to underground walkways and then home. She never appears outside, except when she enters a woodland memory or hallucination, reflecting her sense of feeling trapped by her life yet liberated by fantasy. It’s initially unclear if Enid sees repressed memories of a forest or if watching so many movies has turned the images in her mind into cinematic grammar. Either way, she comes to believe that her sister is alive and appearing in horror movies. It might be a great conspiracy, except her dad reminds her, “We’ve been here before, Enid”—hinting at her history of trauma and delusion. She begins to appear increasingly haggard and pale, but also quite mad when she shows up at the home of a sleazy producer (Michael Smiley) and demands answers to questions about the actress she believes is her missing sister.

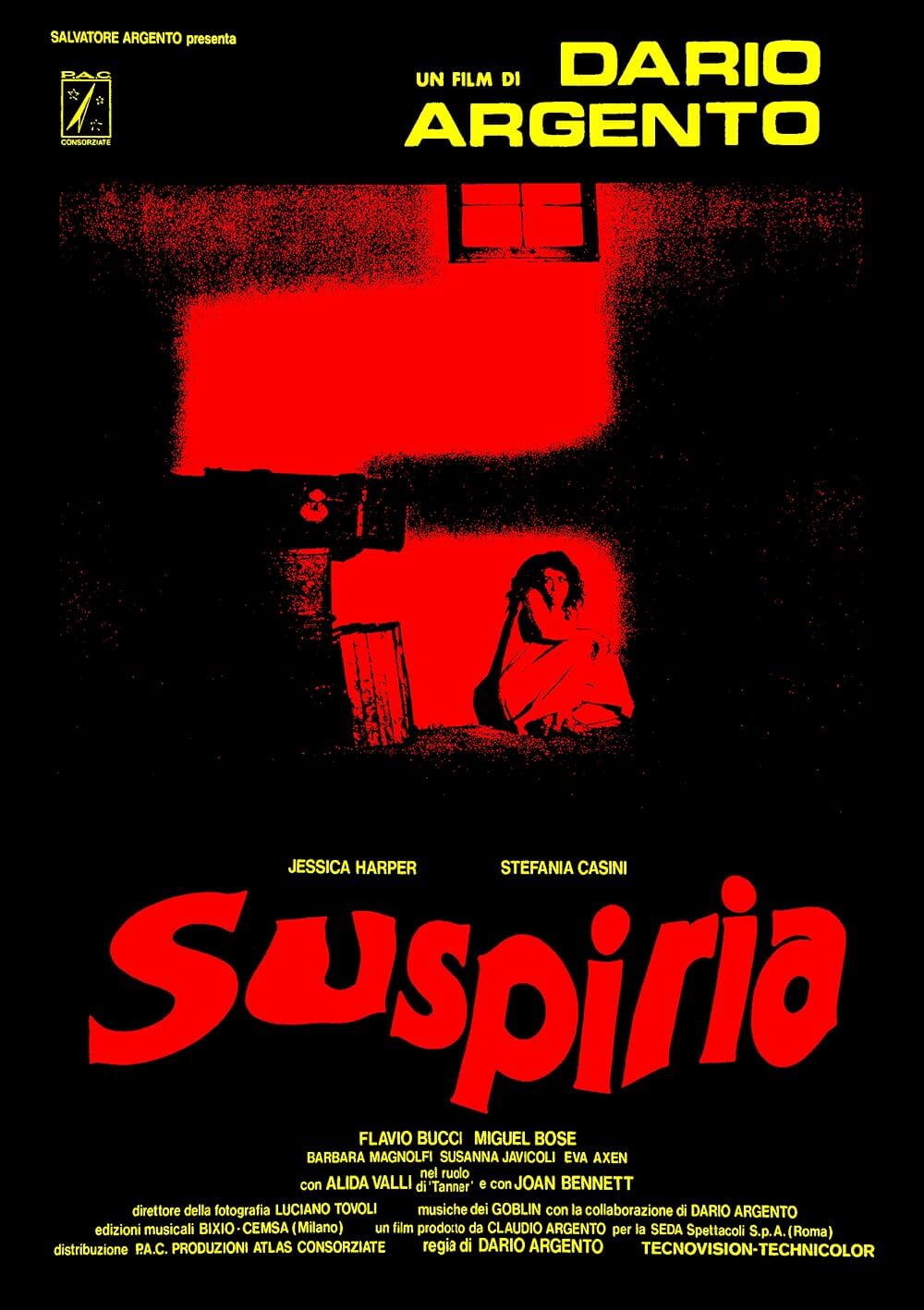

In the last act, Censor morphs from a slow-burning tale of psychosis into Video Nasty-style schlock. The visuals tinted with garish red and blue lighting evoke George A. Romero’s Creepshow (1982)—although a more apt comparison is Shudder’s lame recreation of Creepshow into an anthology TV series, where filmmakers try to approximate Romero’s aesthetic and generally get it wrong. It’s clear what Bailey-Bond is going for, but her attempts at a convincing version of an exploitation film result in silliness. One cannot help but think of Brian De Palma’s Blow Out (1981) and its movie-within-a-movie that perfectly rendered a low-budget slasher. By contrast, Bailey-Bond tries too hard, and her composed movie turns into a dull pastiche that feels less inspired than the first hour of the film. The frenzied, overcooked finale descends into mayhem as Enid’s mind can no longer distinguish between reality and VHS-style visuals. Within the span of the last ten minutes, the movie transitions from axe-murdering madness to surreality. But it doesn’t feel chilling the way it’s supposed to; rather, it feels like it’s reaching for profundity.

There are some inspired ideas behind Censor—specifically, its portrait of the already damaged people influenced by mass media. But the way they’re presented looks and feels underwhelming. Bailey-Bond plays around with the aspect ratio, jolting into pan-and-scan format when Enid goes off the deep end, capturing how movies have taken over her warped mind. The film also takes on the dreamy look of David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986)—a film about the disturbing underworld beneath the idyllic surface of suburban America—suggesting that under the conservative’s exterior lies something corrupt and capable of horror. It’s a fine message, suitably ironic, but the execution cascades into a derivative and overly familiar wink. Censor feels referential and dependent on its antecedents, which makes sense given that movies drive Enid mad. But ideas aside, the film doesn’t stick its landing and leaves the viewer appreciating what it has to say more than how it makes us feel.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review