Cell

By Brian Eggert |

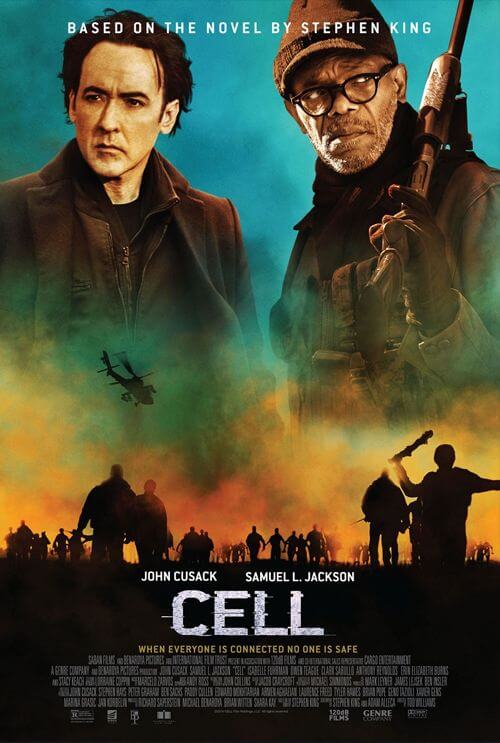

Having read and enjoyed Stephen King’s fast-paced novel Cell, the prospect of a film based on his 2006 zombie yarn proved exciting, if only for a fresh take on the well-treaded subgenre. In this book more than in most of his stories, King wrote passages with such clear cinematic vision that I couldn’t help but see the story making a fine film. To be sure, King established himself as a literary Hollywood unto himself through prose that was written to be visualized, and he connected with his readers by utilizing familiar cinematic touches in his prose. Perhaps this explains why King has been adapted to film more than any modern author, even if the results are sometimes corny and disappointing.

But the film version of Cell goes beyond another corny and disappointing King translation like Pet Sematary (1989) or 1994’s TV miniseries based on The Stand. Though Eli Roth (The Green Inferno) was originally slated to direct, Tod Williams (Paranormal Activity 2, 2010) helmed the adaptation into something bordering on unintelligible. At the very least, the film bears little resemblance to the book. In fact, reading the book might be the only way viewers will understand what’s happening in Cell, since the screenplay, written by King and Adam Alleca (The Last House on the Left remake), leaps over otherwise crucial story elements like plot, character, and drama.

The film opens as graphic novelist Clay Riddell (John Cusack, also co-producer, and star of two other King adaptations, Stand By Me and 1408) gets off a plane at the Boston airport. He calls his estranged wife and their son, but his phone battery dies. It’s a good thing too, since all at once, people in the airport begin grabbing their heads and screaming, and then screeching and attacking the few remaining people who aren’t acting totally bonkers. Clay notices someone trying to make an emergency call, but her cell phone unleashes a pulse that turns her into one of many phone zombies, later dubbed “phoners”. Williams had already used the opening credits montage to show us how virtually everyone in the airport is using a cell phone, as if this is new to modern viewers, and so the exposure to the pulse is total.

As Clay narrowly escapes death, the viewer feels uninvolved and unsure of what’s going on, in part because his character isn’t given a personality, and Cusack isn’t interested in creating one. With the power out due to a badly animated CGI plane crash, Clay soon finds a stalled subway car filled with normal humans, all of whom want to stay put. He teams with the train’s conductor, Tom McCourt (Samuel L. Jackson, also in 1408), and the two resolve to walk the subway tunnels to safety. This initial chaos is filmed with wobbly cameras by Michael Simmonds and pieced together with little shot-by-shot cohesion by editor Jacob Craycroft, qualities that amount to the only consistent aspect of Cell—its inconsistency. If the garbled visuals weren’t enough, Williams can’t seem to orchestrate tension. And though we keep hoping for the proceedings to improve, they never do.

Clay and Tom soon join with the former’s neighbor, the teenaged Alice (Isabelle Fuhrman), and together the threesome heads out to find Clay’s son, a noble cause dramatically muted by the screenplay’s utter lack of dramatic oomph. The majority of Cell takes place on the road, interrupted by episodic encounters with humans and phoners alike, bearing a certain similarity to AMC’s The Walking Dead. Each encounter feels underwritten, with each new character given a few one-note lines and then quickly disposed of. All the while, phoners supposedly learn, grow smarter, and exhibit ever more intelligent and unique behavior, but the audience does not see and cannot track this progression. So little screentime is devoted to the phoners that they remain indistinguishable from your run-of-the-mill zombies—mindless, screaming, violent things—instead of the psychic, ever more interesting and mysterious phoners in King’s book.

King’s authorship is best left to his novels. Whenever he attempts a screenplay, the results end up being dismal and lifeless, like Cell. He adapted the aforementioned Pet Sematary into a glaring disappointment. Or consider his original screenplay for Maximum Overdrive (1986), his first feature film directing effort about machines coming to life and killing human beings—it demonstrated how his writing desperately needs another author in the adaptation process. Remaining blindly faithful to King’s source material results in an unwieldy outcome, in part because his appeal resides in how his prose constructs the narrative, whereas dialogue remains his weakness. Granted, writing isn’t the only problem with Cell, but that’s where it starts.

This long-troubled production completed filming back in 2013 yet failed to find a distributor. The outcome looks and feels like something the distributors carelessly rushed to complete in post-production, if only to secure their investment. Then they dumped the product onto VOD and into a limited theatrical release. As a result, Cell contains an entire cast of underused actors and laughably bad production values. Take the CGI, from the gasoline sprayed on phoner hordes to the eventual fire after it ignites, and finally the hordes themselves—it’s all rendered with about the same quality FX of The Lawnmower Man. The film’s lifelessness and sloppiness represent an all-time-low for King adaptations, which is saying something. And while normally I might argue that fan disappointment makes a bad adaptation just seem worse, in this case, the film is awful on its own, despite any disappointment fans may feel.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review