Celebrity

By Brian Eggert |

For decades, Woody Allen has been a recluse filmmaker, autonomous and secretive in his film productions and all but nonexistent in his films’ promotional campaigns. He rarely makes public appearances and seldom still does he appear at awards shows. Though he’s been nominated for a record 23 Academy Awards and won 4, he’s never attended the ceremony to acknowledge the honor, as he finds the awards themselves to be a popularity contest—more about the politics of the voters than who deserves the awards. He remains a rare kind of celebrity, an icon whose status endures though he takes himself out of the spotlight to devote his full concentration to his particular form of art, which has come at a steady pace of one-film-per-year since the early 1970s.

In Allen’s Celebrity, there’s a scene where an old woman questions why a released political hostage becomes famous. “What’s he famous for, for being captured? …Why is he a hero? It’s no great feat to be captured.” Allen’s 1998 film questions America’s obsession with and reverence for celebrities, how we glorify people who have done very little worth celebrating, and how even the most mundane of people become famous. Some seek out such a life and never acquire it, others have their brief fifteen minutes, and others still have obtained celebrity for a lifetime. We live in a culture that places tremendous importance on fortunate and honored people, and yet these people are often not what we would call role models. But our culture elevates them to a status through which they’re so revered that, more often than not, they are pardoned for their downfalls. Moreover, celebrity is not a status that necessarily requires exceptional talent or skill; Allen recognizes that fame becomes dependent on one’s ability to become a product that can be bought and sold on the covers of magazines.

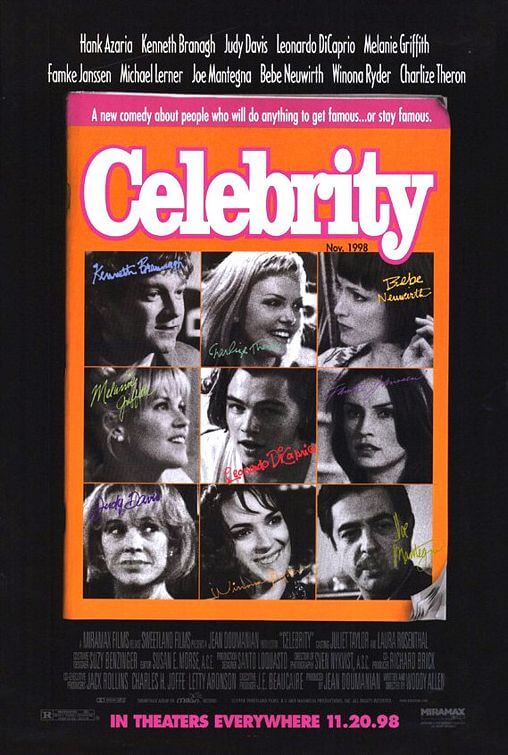

Through characters suffering Allen’s customary string of relationship infidelities and desire for success, the film explores the phenomenon of celebrity in America, specifically New York City, in a series of episodic encounters. Journalist and struggling writer Lee Simon (Kenneth Branagh) interviews movie stars, crashes an art gallery opening and attends dinner parties hosted by literary minds, hoping to find himself an “in” that will produce his long-in-development heist movie script. Lee has recently left his schoolteacher wife, Robin (Judy Davis), to lose himself in this world of random trysts with beautiful people, but, having married too young, his latent desire to explore leaves him lonely. Robin, meanwhile, recovers from the divorce and finds new love in a kindhearted producer, Tony (Joe Mantegna), who, throughout the course of the film, helps Robin cast aside her feelings of inadequacy to become a TV personality. At the same time, Lee finds that his desperate need for professional success destroys any chance he might have at finding love. Like most Allen protagonists, Lee realizes far too late that love is all that matters in life.

Upon its release, Celebrity was met with high-toned dismissals from critics who saw Branagh and Davis’ performances as nothing more than extensions of Allen’s own onscreen persona. Davis’ character begins as a female version of Allen, with Allen’s mannerisms and neuroses intact until, toward the end of the film, she becomes poised, confident, and ultimately happy. It was Branagh’s performance that seemed to affront critics more. Variety’s Todd McCarthy called Branagh “simply embarrassing as he flails, stammers and gesticulates in a manner that suggests a direct imitation of Allen himself.” Roger Ebert was more forgiving and praised Branagh’s ability to channel Allen’s onscreen mannerisms, remarking that Branagh “does Allen so carefully, indeed, that you wonder why Allen didn’t just play the character himself.” The answer is simpler than one might think, as Allen has admitted that, being 63 at the time, he was too old to play Lee Simon, someone capable of attracting young models and actresses. But Branagh’s—and to an extent Davis’—uncanny ability to “play Woody Allen” is not a fault of the film; if anything, the actors’ embodiment of Allen’s characteristics help remove Allen himself from the equation (even while they draw attention to Allen’s absence).

Because Allen’s actors chose to portray their roles in such a way, critics pigeonholed Celebrity as Allen’s very intimate and pessimistic reaction to his own personal troubles with the media. This was a narrow view at the time, and remains so, and was not the first time the writer-director’s work had been interpreted as autobiographical. When Allen released Stardust Memories in 1980, critics questioned his intentions as he played a film director who is hounded by obnoxious fans and critics and producers, taking the film as Allen’s own subjective commentary on the film industry. Allen insists this was not so, that his film was just a story about the plight of any filmmaker; but he learned his lesson about how audiences read his presence in films to be directly “about” himself within the industry. That same lesson was learned after Husbands and Wives (1992), a film that earned Allen criticism for writing too closely about his perceived personal affairs that had erupted during the film’s production. In 1997’s Deconstructing Harry, within the narrative Allen explored the trend of an audience’s misinterpretation that every detail in an artist’s work has an autobiographical correlation. And for Celebrity, Allen makes a choice (conscious or not) to lessen such an interpretation by casting another actor in his familiar protagonist role. Here, Allen distances himself from the work and, hopefully, eliminates any chance of a close autobiographical reading of the film.

It’s one of the great misconceptions about Allen’s work that each film has some deep-rooted personal underpinning, as opposed to inspiration. Not every Woody Allen film is about Woody Allen and his personal life. For viewers in 1998, who were then much closer to the tabloid fodder of Allen’s off-screen affairs, this was doubly true. Up to the release of Celebrity, Allen’s films were, by and large, products of the filmmaker’s well-known persona. Only a few irregular exceptions had emerged that derived from someplace other than the characteristic “Woody Allen” spirit, such as Interiors (1978) and September (1987) and Another Woman (1988)—all of which adopted a Bergmanesque dramatic tone and style of dialogue that, without Allen’s name on the credits as writer-director (he did not appear onscreen in these films), could not be assigned to him simply by viewing the film. And so, watching Celebrity with Branagh employing such recognizable Allen-isms, one cannot help but look for correlations to Allen’s life. Nevertheless, the film is less about Allen himself than it is an exploration of his philosophy on the status of celebrity and fame in America.

As most critics have pointed out, Allen’s tale takes on an episodic configuration, but some called it “meandering” and faulted the story for having no forward momentum. However episodic it may seem, the narrative is actually tightly structured so that if one component went missing, it would fall apart. Early on, when Lee and Robin bump into each other at a movie prescreening after their divorce, Lee is accompanied by a beautiful woman and appears confident; Robin squirms, desperate to hide from her ex. As the story goes on, Lee floats between his clingy meetings with movie stars and gradually spins downward on a social slope, his self-centered narcissism driving him from one broken relationship to another, always desperate to pitch first his screenplay and then his book. Each of his intervallic run-ins with famous people takes him a step closer to loneliness and failure until, finally, he is alone. At the same time, Robin begins as an abandoned wife but gradually finds love and, in time, fame. When Lee and Robin meet in the finale at another screening, their statuses have flip-flopped. As opposed to episodic, Allen’s structure is comprised of two ongoing stories that come together in an elliptical conclusion. Rather like Annie Hall (1977) and Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989), the film has a deceptively structured ruminative quality.

Of course, each interval in Lee’s series of “adventures” with various (fictional) celebs is memorable in its own way, particularly given Allen’s star-studded cast, lending to Celebrity’s episodic feel. But each one also lowers Lee to new depths in his self-deprecating quest for celebrity. He begins by flirting with a superstar actress played by Melanie Griffith, who gives Lee an exclusive interview; Charlize Theron’s supermodel role fulfills another “polymorphously perverse” Allen character; then he finds himself flying to Atlantic City and narrowly participating in an orgy with Leonardo DiCaprio’s hotel-thrashing teen heartthrob actor, who’s too busy partying to discuss Lee’s script. Lee’s episodes become less glamorous as the film goes on. Famke Janssen plays his new editor girlfriend, Bonnie, a woman who loves him but he betrays. And as his self-destructive midlife crisis takes over, Lee finds himself clinging to Winona Ryder’s striking but comparatively shabby movie extra. Still, the star power of this cast is enough to distract from the film’s overall structure, especially today when looking back at these performers before many of them became superstars (DiCaprio and Theron in particular).

The disconnect—why, for the most part, even Allen’s most devoted audiences consider Celebrity one of his lesser efforts—may result from the film’s string of irredeemable characters and its pointedly bleak outlook on these people. They’re intentionally written as shameful, morally horrible illustrations of fame at its worst. But this is the thesis of the film. We’re not supposed to identify or especially like these characters, no matter how attractive or charismatic or superficially appealing they may seem. All of the phony business meetings and false promises and appointments and bullshit, all of the parties at night clubs and movie screenings and even high school reunions, everyone kisses ass and represents themselves as successful to draw the envy and approval of others. Audiences who leave this film feeling disgusted by the showcased behavior have experienced the correct reaction. Such a reaction is so rarely the desired effect in cinema that audiences are often left befuddled by such films, equating the experience to a bad one, though the film proved to be effective. After all, even the reasonably likable character of Robin gives up a schoolteacher position for a glitzy blonde hairdo and a microphone; she may be a casualty of Lee’s pursuit of fame, but she has also sold herself.

The last of four films shot for Allen by cinematographer Sven Nyqvist, Celebrity looks gorgeous in rich monochromatic photography that lends all the pretty faces onscreen a kind of candid tabloid reality. Along with a score accentuated by Gershwin and booming Beethoven, Nyqvist’s lensing adds deeply poetic moments to the film, such as the scene where Bonnie tosses the only copy of Lee’s manuscript from a ferry, or in the final shot when a skywriter inscribes “HELP” in the sky and signifies both Lee’s feelings and Allen’s. But in spite of Allen’s censures, he doesn’t lose his sense of humor, as Mantegna’s character quips in a knowing line, “He’s very arty, pretentious, one of those assholes who shoots all his films in black & white.” Although most closely aligned with another Allen film about fame shot in black & white, Stardust Memories, this one remains the more challenging piece from the standpoint of the viewer, who must not only reconcile Allen’s satiric intentions with his (ironically) celebrity-filled cast but performances that are derived from the man himself. The film remains an unusual Woody Allen film, one difficult to place in his oeuvre, but a memorable one worth revisiting and, ultimately, debating.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review