Cave of Forgotten Dreams

By Brian Eggert |

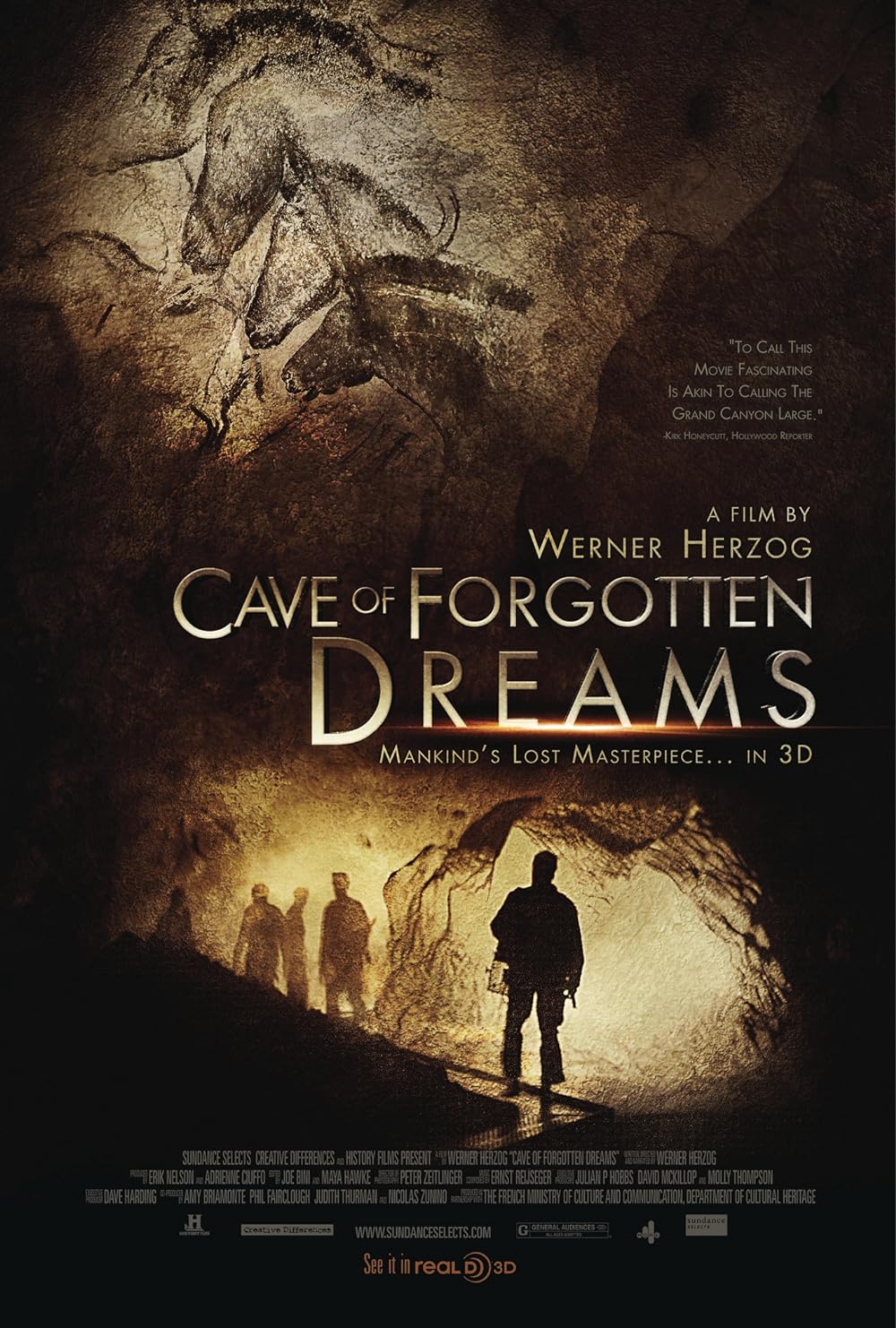

Art history belongs not in textbooks but in museums, where the presence of artwork can be felt and overwhelm the spectator. Mere photographs of paintings or sculptures alter true colors and remove any sense of perspective, reducing or altogether eliminating the awe evoked when face-to-face with a work of art. Filmmaker Werner Herzog goes to great efforts to transform cinema into a “really there” museum experience in his documentary Cave of Forgotten Dreams, where he explores prehistoric paintings some 32,000 years old in the Chauvet Cave in southern France. Utilizing the latest cinematic technology (such as 3D in select theaters) to immerse his audience in an experience that is truly once-in-a-lifetime, the renowned filmmaker’s insightful narration and ponderous camera creates a spectacle for the senses, both intellectual and spiritual.

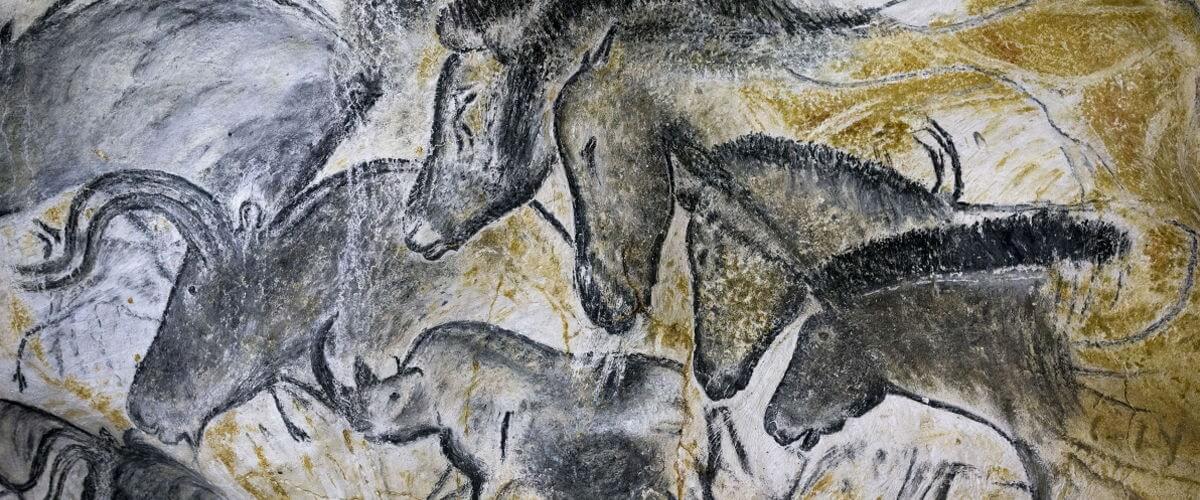

In 1994, not far from France’s Ardeche River, a group of scientists discovered the minuscule but drafty opening to Chauvet Cave, a system perfectly preserved when a rockslide during the Ice Age sealed the entrance and left it out of reach. Inside, ancient cave bear skulls have been preserved, while other bones are covered by thousands of years of calcite accumulation. Mineral formations that take millennia to build up and down from the cavern walls glitter with crystals. But on the cave walls are the most magnificent sights: charcoal drawings of horses, lions, bison, rhinoceros, and other animals, bending with the contours of the rocks to form the illusion of movement. Herzog describes it as “a form of proto-cinema”. And for a period in the film’s second half, his camera pans over the images, fading in and out in an evocative, awe-inspiring reflection punctuated by Ernst Reijseger’s haunting string score.

In the spring of 2010, Herzog and his four-person crew—including cinematographer Peter Zeitlinger and his probing handheld digital camera—were allowed inside Chauvet Cave with a team of scientists, including archeologists, anthropologists, geologists, art historians, and others. The first filmmaker permitted by the French Ministry of Culture to shoot inside, Herzog and his crew were allowed only a few hours per day to shoot, as tree roots penetrating the cave build toxic levels of carbon dioxide. Using a battery-powered camera and low-heat lights, the crew was restricted to a two-foot-wide plank that protects the delicate cave floor, causing limited maneuverability and possible camera angles. They’ll likely be the last film crew allowed inside, as similar caves have been spoiled by frequent tourists, the moisture in their breath causing mold to grow on cave walls, compromising the integrity of a natural time capsule.

Of course, the director has faced more perilous locations. He ventured countless miles in Encounters at the End of the World (2007) to explore the cold and isolation of Antarctica and the people who choose to live there. He followed scientist Dr. Graham Dorrington to Guyana in The White Diamond (2004), a dangerous attempt to capture a unique camera perspective and test a curious flying machine high above Kaieteur Falls. And he spent a month shooting Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans (2009) with Nicolas Cage as a drug-addicted cop, an experience bound to be dangerous for all involved. His most famous and perilous journey was in the Peruvian jungle, where he challenged nature with technology to shoot Fitzcarraldo (1982), a film about an opera fanatic who attempts to haul a 32-ton boat over a muddy hill from one river to another, parallel one.

Here, it’s not the danger of his location or the obsession of his quest, but rather the exclusivity and the rare, personal journey taken by those who enter. The cave walls show evidence of ancient cave bear scratches, human and animal footprints seemingly side-by-side though doubtless separated by millennia, and evidence of ritualized behavior. Inside, Herzog finds what he calls “the beginning of the modern soul”, as something intangible that reaches across time and space occurs within these cave drawings—the first evidence of human beings searching for meaning in the world around them, most prevalently in the deep connection between human and animal. The first images etched into the walls 30-40,000 years ago must have been looked upon with wonder and even preserved for thousands of years afterward by the early humans visiting these caves until they were sealed off. Now, with the same reverence, we share this space with our distant ancestors and form an ethereal connection to our past best described as spiritual. In the final coda, a curious sequence involving nearby nuclear power plants and albino alligators, Herzog considers who will find Chauvet Cave after our era.

This cave will likely never be opened to the general public outside of academia, so Herzog creates for us a link with our past and attempts to recreate the experience of being there through his limited cinematic tools. To say he achieves his goal is an understatement. Through interviews with experts, Herzog paints his own anthropologically informed picture of what life must have been like for those who decorated the cave. Scientists tell us how they would have survived the colds of the Ice Age, hunted and dressed and played music. But more effective is his use of technology to place his audience in Chauvet Cave. His ruminative camera and torch-like lights recreate the way in which early humans would have seen the drawings; he consults a master perfumer to describe the smells in the cave; he embraces the cave’s silence, quiet enough to hear a heartbeat; he employs 3D to give the audience a sense of depth and space. It’s all incredibly effective, enough to draw up emotions that take some time after viewing to fully comprehend.

Picked up by IFC Films for theatrical distribution and by the History Channel for television, Cave of Forgotten Dreams will endure long passed its theatrical run, as this is a film filled with marvel and fascination. Much like Herzog’s Grizzly Man (2005), the film will reach mainstream audiences on cable television and continue to enthrall viewers for ages. It’s a shame, however, that IFC couldn’t be bothered to release the doc wide, or even ensure that every theater showing the film supported the 3D device (many arthouse theaters do not)—this is a film that should be seen in 3D for Herzog’s immersive intentions to work at their fullest. But even in two dimensions, Herzog delivers a documentary so powerful that the result will leave the viewer more than just well-informed but transported by the experience.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review