Reader's Choice

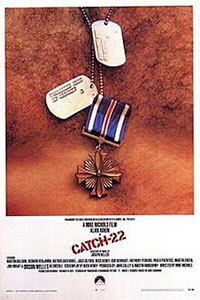

Catch-22

By Brian Eggert |

Catch-22 rethought the notion of American heroes and wartime virtue for the counterculture movement of the 1960s. Americans think of World War II as a “Good War,” where its heroic boys fought with a sense of moral conviction and came out victorious. It’s easier that way. Another perspective is that America was an isolationist country, and it didn’t join the war out of some ethical responsibility to do the right thing and stop the spread of fascism, but because it was provoked by the attack on Pearl Harbor, and it wanted revenge. No war is ever a matter of black and white. Similarly rethinking the heroic certainty of Americans in World War II, veteran and author Joseph Heller’s novel Catch-22, published in 1961, turns the notion of American heroism into a topsy-turvy concept. Part of the 1960s anti-establishment that began to reconsider the status quo, Heller’s novel introduced the concept of the “catch-22” into our vernacular, underscoring a maddening and bureaucratic circular logic. When the story’s hero, Yossarian, a bombardier in a B-25, asks to be removed from duty, suggesting it’s driving him insane, his doctor replies that any soldier who wants out of combat duty isn’t really crazy. With this, the doctor admits that it’s natural to want to escape combat but also unacceptable to do so; it’s natural to go crazy in the face of war but also inconvenient to the cause.

After Heller’s book was published, a Hollywood adaptation seemed the next likely step, and audiences were clamoring to see it. With the Vietnam War in full swing and antiwar protests sweeping the United States throughout the 1960s, Heller’s potent and satirical jab at the American establishment was a call to the emergent youth culture that increasingly questioned its authorities. Ever the anti-authoritarian, Orson Welles had been talking about bringing it to the screen for years, and Heller was all for it, except that Welles, as usual, struggled to secure the necessary funds. Eventually, the adaptation fell on director Mike Nichols, whose 1967 landmark The Graduate was another film that turned traditional American conventions (college, adulthood, marriage) on their head. Overshadowed by Robert Altman’s similarly themed M*A*S*H, released just a few months before in 1970, Nichols’ ambitious take on Catch-22 was ultimately met with mixed responses from critics and audiences. Sight and Sound critic Stephen Farber called it “an unquestionable failure,” and Roger Ebert’s otherwise positive review called it a “disappointment.” Revisiting the film today, its ambitions and acting remain admirable, but its overall effect is wavering.

However, Catch-22 is not the comedy of horrific ironies that M*A*S*H proves to be; it is a frustrating array of Kafkaesque scenarios and military logic twisted into a dehumanizing reality. Every joke in the film doubles as an expression of military disenchantment. Buck Henry, who wrote the screenplay, delivers a take on the classic bit “Who’s on first?” and incorporates potent visual gags—such as nurses who conduct a curious exchange of fluids for a soldier in a body cast—that make every laugh hurt. What works best about the film nearly 50 years later is the melancholy that is attached to every laugh. Less successful is how Nichols operates in non-chronological order, leaping from one association to the next with a series of visual and aural bridges achieved by editor Sam O’Steen. The story becomes secondary to the uses of form, which function to underscore a darker, surreal fabric that holds Catch-22 together. Nichols did not make an easy film; he challenged his audience to think about every moment, disentangle it, and decipher its purpose beyond the surface text. Regardless of how deliciously confrontational it proves, it’s a film more easily admired than loved.

Catch-22 begins at the end, where Yossarian, played incredibly by Alan Arkin in a role that he later called disastrous to his early career, talks to his superiors, Cathcart (Martin Balsam) and Korn (Henry). Their exchange cannot be heard over the squadron of bombers leaving the airbase in Pianosa, which is a perfect metaphor for Heller’s view of the war—a conflict devoid of discussion when action will do. A moment later, Yossarian has been stabbed in the back, literally, and the ensuing film seems to occur in a near-death fever dream. Unspooling at random in his head are scenes that have an episodic quality, yet they connect to one another by transitional devices in the form of match cuts, visual parallels, and verbal associations—the patchwork of the mind. One scene leads into the next, resulting in a kind of loose if non-linear progression that intentionally disorients the viewer. At the same time, Nichols intersperses a development of segments from Yossarian’s haunting nightmare, where he tends to a dying bombardier named Snowden, whose insides are spilling out after an attack—the catalyst that leads to Yossarian wanting out of the war in the first place.

Catch-22 begins at the end, where Yossarian, played incredibly by Alan Arkin in a role that he later called disastrous to his early career, talks to his superiors, Cathcart (Martin Balsam) and Korn (Henry). Their exchange cannot be heard over the squadron of bombers leaving the airbase in Pianosa, which is a perfect metaphor for Heller’s view of the war—a conflict devoid of discussion when action will do. A moment later, Yossarian has been stabbed in the back, literally, and the ensuing film seems to occur in a near-death fever dream. Unspooling at random in his head are scenes that have an episodic quality, yet they connect to one another by transitional devices in the form of match cuts, visual parallels, and verbal associations—the patchwork of the mind. One scene leads into the next, resulting in a kind of loose if non-linear progression that intentionally disorients the viewer. At the same time, Nichols intersperses a development of segments from Yossarian’s haunting nightmare, where he tends to a dying bombardier named Snowden, whose insides are spilling out after an attack—the catalyst that leads to Yossarian wanting out of the war in the first place.

The jarring relentlessness of these scenes and their connectivity make watching Catch-22 a challenge, sometimes in a rewarding way; at other times, it feels like a chore, as the viewer can see the machine at work. From the outset, we cannot help but feel drawn to the material because of the cast. Nichols brings together an impressive ensemble including Bob Balaban, Marcel Dalio, Art Garfunkel, Charles Grodin, Bob Newhart, Anthony Perkins, Martin Sheen, and Jon Voight. Each of them has an arc that twists from something comical into something either disturbing or acerbic. Newhart is hilarious as Major Major, the officer who refuses to take meetings anywhere but his office, though he scurries out the window when his appointments arrive. Voight plays Milo Minderbinder, a soldier doubling as a black marketeer who turns military equipment into profits, gradually revealing how the opportunism of American capitalism has seeped its way into the military. Grodin plays Yossarian’s seemingly reasonable friend who turns out to be a rapist of a local woman, a crime that MPs are less concerned with than Yossarian’s dereliction of duty.

Throughout the proceedings, it’s impossible to ignore a pattern of references, intentional or not, to Stanley Kubrick’s own antiwar films. One cannot watch Catch-22 without thinking of Dr. Strangelove (1964), specifically during a scene where Yossarian’s bomber approaches the wrong target. Elsewhere, Dr. Strangelove’s military leaders, with their circular logic and the soul-crushing bureaucracy within their ranks, reveals, in a similar way that Heller does, how military language follows disturbing patterns. Cathcart says at one point, defending an arrangement he made with the Germans to bomb the U.S. airbase, “A contract is a contract. That’s what we’re fighting for”—a line recalling, “You can’t fight in here! This is the War Room!” from Dr. Strangelove. Another sequence involves Brigadier General Dreedle (Welles, hilarious in his few scenes) suggesting that one of his own soldiers be executed for disobeying orders, recalling the central conceit of Kubrick’s Paths of Glory from 1957. Finally, in one of the too many scenes where Nichols’ camera ogles the female form, Richard Strauss’ “Thus Spoke Zarathustra” echoes the use of this music made famous just two years earlier in 2001: A Space Odyssey—marking perhaps cinema’s first of many parodies of Kubrick’s transcendent science-fiction masterpiece.

But Nichols’ commitment to the confrontational nature of Heller’s text results in several uncomfortable and unflinching sequences, which distinguish the film from more comedic satires like Dr. Strangelove or M*A*S*H. Heller himself praised the film for walking the line between comedy and antiwar message, which keeps the viewer on edge. The graphic image of Snowden’s guts oozing out of his body (a practical effect achieved long before Tom Savini used it for zombie purposes in Day of the Dead) causes an involuntary gag. Lines like “All great countries are destroyed. Why not yours?” challenge pro-American ideologies. And a sequence late in the film finds Yossarian walking through a series of Roman alleys, where he witnesses no end of debauched behavior—a man beating a horse, a prostitute fellating a customer, and children robbing a drunkard. At every turn, the film challenges moral idealism with the corruption of humanity.

But Nichols’ commitment to the confrontational nature of Heller’s text results in several uncomfortable and unflinching sequences, which distinguish the film from more comedic satires like Dr. Strangelove or M*A*S*H. Heller himself praised the film for walking the line between comedy and antiwar message, which keeps the viewer on edge. The graphic image of Snowden’s guts oozing out of his body (a practical effect achieved long before Tom Savini used it for zombie purposes in Day of the Dead) causes an involuntary gag. Lines like “All great countries are destroyed. Why not yours?” challenge pro-American ideologies. And a sequence late in the film finds Yossarian walking through a series of Roman alleys, where he witnesses no end of debauched behavior—a man beating a horse, a prostitute fellating a customer, and children robbing a drunkard. At every turn, the film challenges moral idealism with the corruption of humanity.

When it’s not pummeling the viewer with a series of grim realities, Catch-22 is quite often laugh-out-loud funny, making the most of the dizzying logic that informs the title. But the humor ranges from the absurdist to the dreamily paranoid. In the former category, watch the scene where Yossarian shows up buck naked to receive a medal, and Welles’ Dreedle responds with a flatly delivered, “You are a very weird person.” In the latter category, note the “disappearance” of Doc Daneeka (Jack Gilford) who, due to a clerical error, does not exist any longer according to military law, and therefore the other characters cannot, or refuse to, see him. No wonder he’s the one to disappear, as the Doc first introduces Yossarian to the “catch-22” logic that is present throughout the film. Moreover, he’s a character whose vocation is to save lives, and yet the military refuses to allow him to save lives. He’s forced to keep soldiers like Yossarian in the war, to keep them fighting until they die. It’s the foremost of the film’s enduring paradoxes that would overwhelm with their oppressive, nightmarish circularity if not for the distinct brand of Heller’s humor.

It’s a further irony that Catch-22 opens with Yossarian’s stabbing, as getting knifed in the back is the only way he can escape the military. Writing from his own experience, Heller uses Yossarian’s closeness to death to underscore a larger point about the futility and absurdity of war, even the “Good War,” and it’s a message that resonates beyond the film. Mostly, the message emerges as we bear witness to Yossarian cracking up—a progression impressively performed by Arkin, who was unfairly stigmatized after Catch-22‘s release because he was its star, because it failed to live up to Heller’s novel, and because it was overshadowed by the sensation of M*A*S*H. Yossarian’s madness is the perfect symbol to encapsulate the overall message and structure of the film, even if it’s communicated within an endless barrage of asides, assembled by his subconscious into a meandering and somewhat unsatisfying whole. Despite countless individual moments that result in humor, or alternatively, biting truth, the experience of watching Catch-22’s inherent unevenness wears on the viewer. It’s an easier film to intellectualize than it is to enjoy, and one finds that while its message, however harsh, is agreeable, its methods are less so, even as they prove thoughtfully made.

(Editor’s Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your support, Ron!)

Bibliography:

Heller, Joseph. Catch-22. Simon & Schuster, 1961.

Stevens, Kyle. Mike Nichols: Sex, Language, and the Reinvention of Psychological Realism. Oxford University Press, 2015.

Whitehead, J.W. Mike Nichols and the Cinema of Transformation. McFarland & Company, Inc., 2014.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review