Cat People

By Brian Eggert |

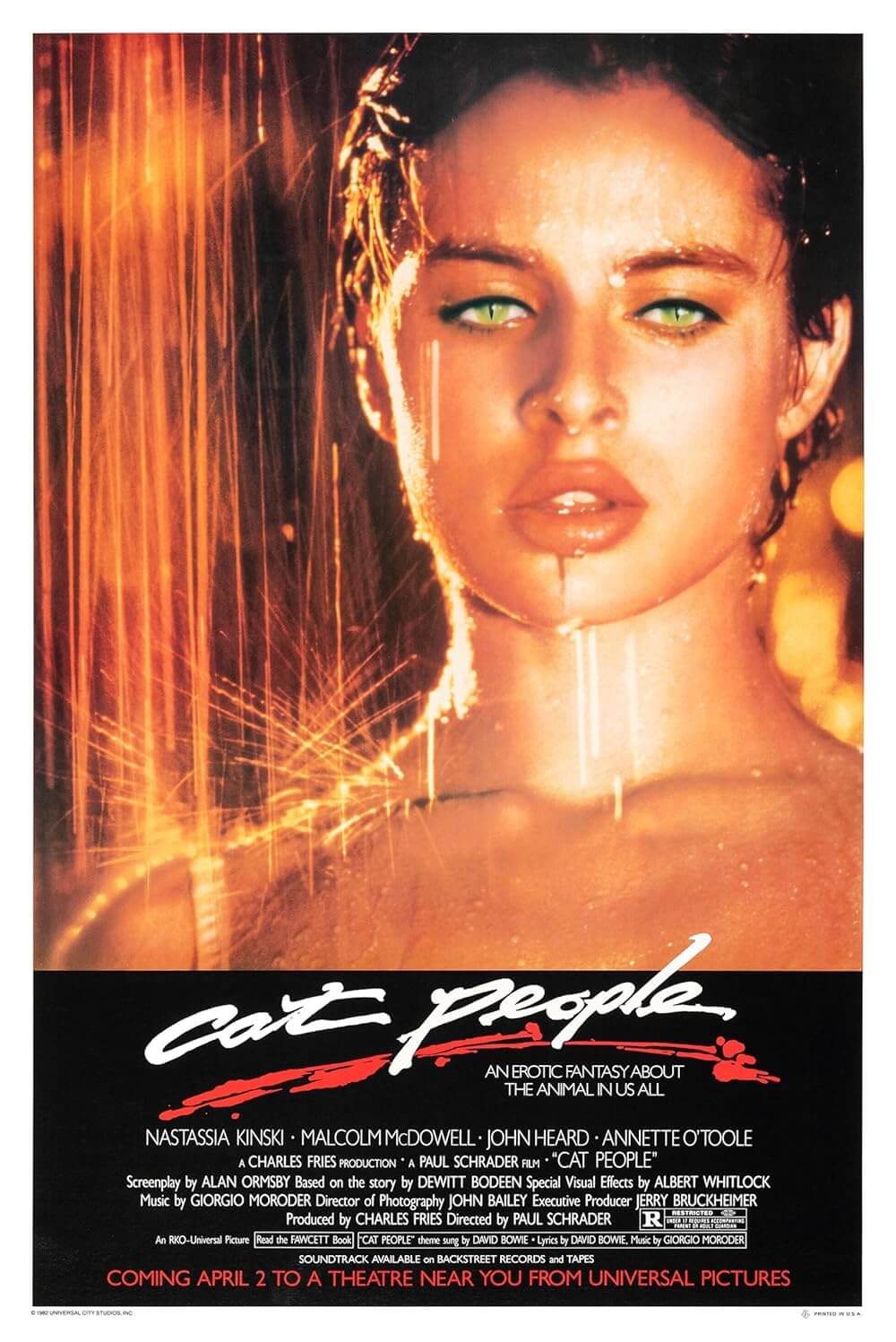

Paul Schrader’s 1982 version of Cat People opens with David Bowie’s low voice humming the film’s theme, the titular song that bookends this psychosexual thriller of metamorphosing were-cats, incestuous relationships, and a sadomasochistic resolution to the protagonist’s lustful desire. Bowie’s voice captures the deep sexual and mythic implications that follow, setting the tone against the film’s first images: On an apocalyptic landscape, high winds unearth skulls from beneath a red desert. In the distance under a skeletal tree, a melanistic leopard (black panther) cries into the distance. The villagers in this unspecified place and time conduct a ritual sacrifice, offering a young woman to the beast. Or perhaps it was an arranged sexual encounter. In either case, the villagers awake the next morning to find the surrounding desert has been replaced with blue skies and vegetation. Mysticism and animal sexuality mark Schrader’s baroque experiment in arthouse style and commercial sensibilities, a remake that takes everything inward and psychological about the 1942 original and leaves it splayed onto the screen.

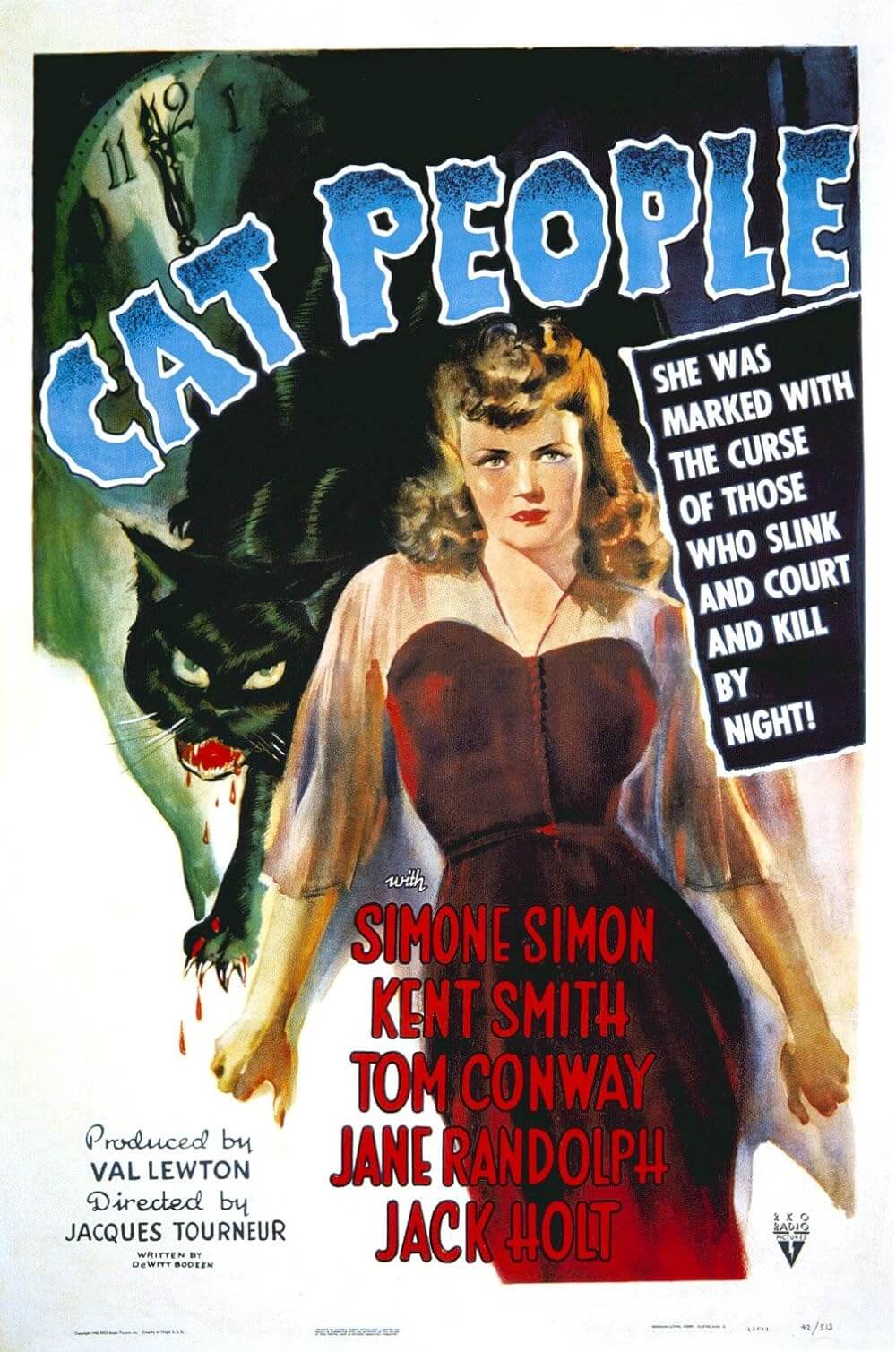

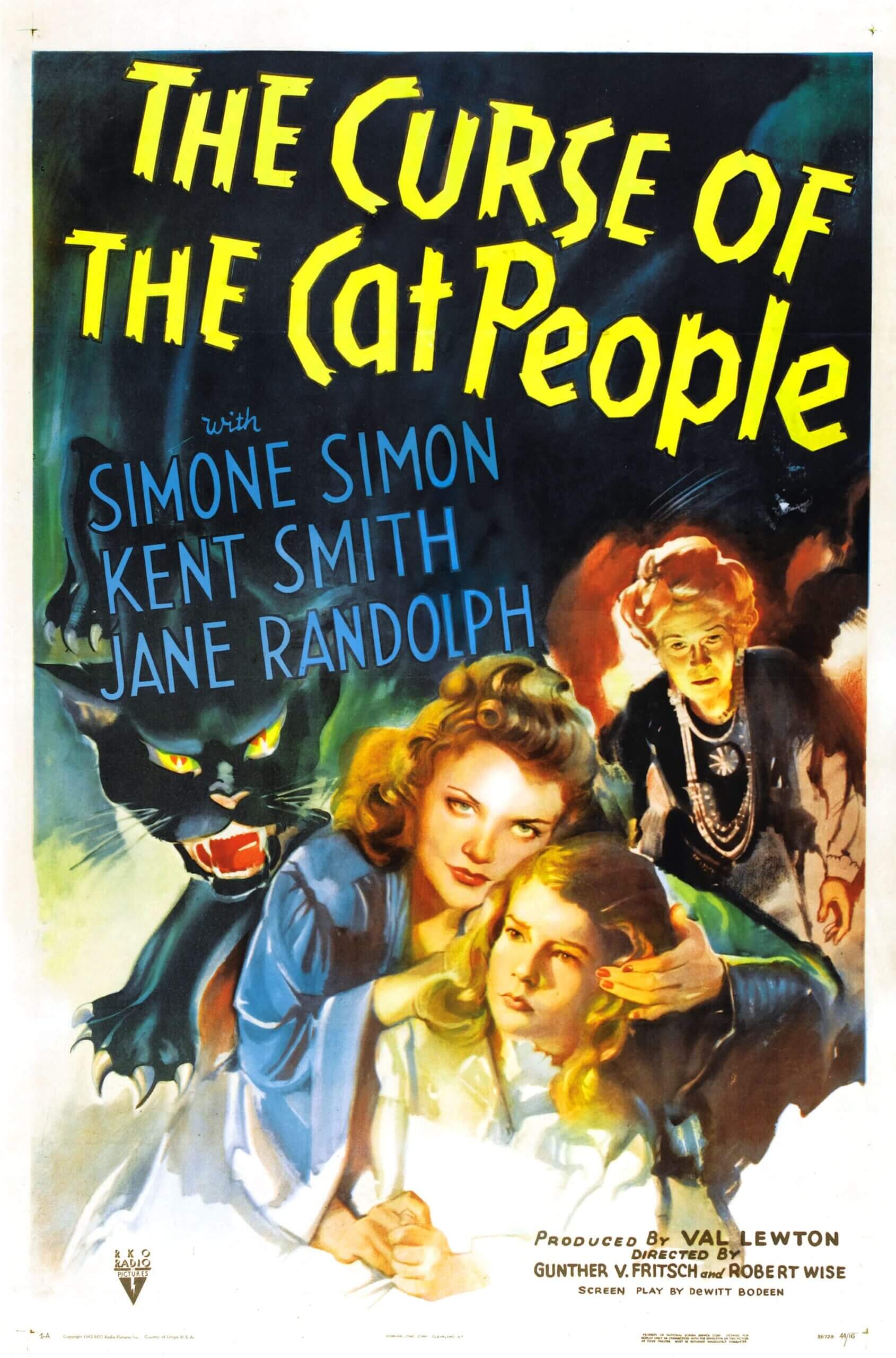

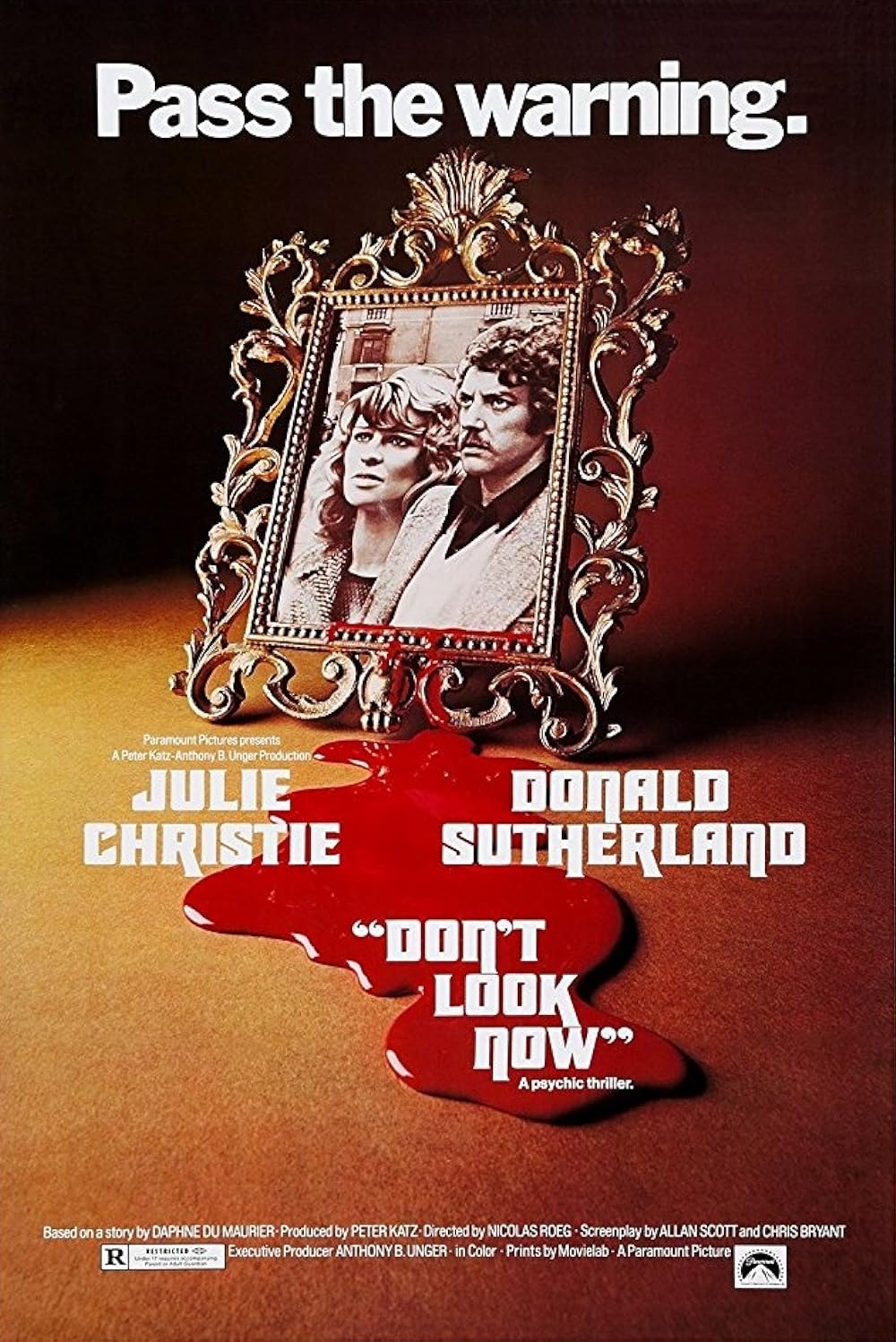

As remakes go, Cat People does what a lot of films based on classic Hollywood horror did in the 1980s and 1990s—it brings the subtext of the dark original out of the shadows. Titles like John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982), David Cronenberg’s The Fly (1986), and Martin Scorsese’s Cape Fear (1991) explored the physical, scientific, sexual, and metaphorical limits of their predecessors’ unconscious or corporeally unrepresented phenomena. Directed by Jacques Tourneur and produced by Val Lewton, the original Cat People remains haunting for the innate psychological drives and sexual anxieties of its central cat person, a reluctant monster whose transformations are hidden beneath the film’s essential, masking shadows and surface text. By contrast, Schrader and other filmmakers render what, in an era bound by the Production Code and restrictions for onscreen sex and violence, could not be shown. Schrader’s film and the three examples listed above also stand as exceptions, in that most adaptations of this kind (such as, say, Chuck Russell’s gory 1988 remake of 1958’s The Blob) simply applied new special FX to an old story. But Schrader, Carpenter, Cronenberg, and Scorsese added additional psychological dimensions to their remakes, in addition to copious amounts of blood and sexuality.

Cat People was developed as a studio project at Universal Studios, which had acquired the rights to Lewton’s original from RKO in an effort to exploit a recent Hollywood fad: elaborate, make-up driven werewolf transformations onscreen in An American Werewolf in London, The Howling, and Wolfen—all released in 1981. The outward approach conflicts not only with the transformation-free original film, but also with Schrader’s philosophy on poeticism and aestheticized spiritualism (he wrote a book about Transcendental Style in Film about the cinema of Robert Bresson, Carl Dreyer, and Yasajiro Ozu). The original Cat People involved a character whose sexual resistance prevented her from becoming a monstrous beast even as she yearned for human contact. By contrast, Schrader’s externalization of the characters’ psychological hang-ups results in twisted, grotesque, and erotic cinema that remains compulsively watchable, if often troubling. Always engaging in its use of sexual politics and relationships, Schrader’s Cat People was also marketed as an “erotic thriller” whose hook involves putting star Nastassja Kinski, and other women, on display in a series of sometimes cheap nude and sex scenes.

Cat People was developed as a studio project at Universal Studios, which had acquired the rights to Lewton’s original from RKO in an effort to exploit a recent Hollywood fad: elaborate, make-up driven werewolf transformations onscreen in An American Werewolf in London, The Howling, and Wolfen—all released in 1981. The outward approach conflicts not only with the transformation-free original film, but also with Schrader’s philosophy on poeticism and aestheticized spiritualism (he wrote a book about Transcendental Style in Film about the cinema of Robert Bresson, Carl Dreyer, and Yasajiro Ozu). The original Cat People involved a character whose sexual resistance prevented her from becoming a monstrous beast even as she yearned for human contact. By contrast, Schrader’s externalization of the characters’ psychological hang-ups results in twisted, grotesque, and erotic cinema that remains compulsively watchable, if often troubling. Always engaging in its use of sexual politics and relationships, Schrader’s Cat People was also marketed as an “erotic thriller” whose hook involves putting star Nastassja Kinski, and other women, on display in a series of sometimes cheap nude and sex scenes.

Nevertheless, Kinski is excellent as Irena, a former orphan reunited with her brother Paul (Malcolm McDowell) in New Orleans for the first time since they were small children. Paul lives in a large house with a woman named Female (pronounced Fey-moll-aye, played by Ruby Dee), an underutilized character with whom he shares suspicious, angered glances about the incestuous overtones to the siblings’ reunion. Female seems to know all about Paul, but the virginal (“especially in these days” of the AIDS epidemic) Irena is just re-learning. Irena has only vague memories of her childhood with Paul in the circus; their parents were lion tamers and, as we learn much later, also siblings. With Irena unaware of her cat person origins, Paul attempts to introduce her to Schrader’s revised mythology: For cat people, lust is a literal bloodlust, wherein the cat person must either transform and kill, or satiate their sexual desires with a sibling; should a cat person have sex with a non-sibling, they will immediately transform and likely kill their sexual partner. At least, this is according to Paul, who may have made up these rules after seeing his sister.

Schrader makes superior use of Irena’s love interest, Oliver (John Heard), who in the original was a dope. The 1982 film repurposes him as a zookeeper whose chummy assistants, Alice (Annette O’Toole) and Joe (Ed Begley Jr.), help him remove a feral panther from a brothel—where it has killed a prostitute and been locked inside a room. They eventually secure the beast, temporarily holding it in a small enclosure at the New Orleans Zoo. A series of killings around New Orleans are attributed to the panther and, eventually, Paul. Of course, Paul remains missing and, somehow, Irena knows that her brother has become a panther. Fortunately, this mystical conceit allows Schrader to improve upon the original’s meet-cute by introducing Irena and Oliver when she visits her panther-brother at the zoo. The two connect immediately. “I prefer animals to people,” he says, explaining why he’s so drawn to Irena.

Setting aside the plot of Cat People for a moment, the production’s treatment of live animals remains a distraction throughout the film. The animals themselves, especially the central Paul-panther, cannot help but remove the viewer from the narrative out of sheer concern and sympathy for the real-life animal’s treatment. The panther looks scared, angry, and nervous, and the pathetic size of the New Orleans Zoo animal pens (a studio set) appears far too small. Admittedly, Oliver mentioned the zoo needs an upgrade and hasn’t been improved since 1942 (the release year of the original film), and he protests the conditions with his superior. But the animals used in the film undoubtedly had to endure small enclosures and prodding treatment to capture the intended result. Clever cutting around a sedated animal (its paw visibly twitching throughout) is used during an autopsy sequence, which seems like an unnecessary risk to take. Anyone with an ounce of sympathy for the treatment of animals will find the film difficult to endure for that aspect alone.

Setting aside the plot of Cat People for a moment, the production’s treatment of live animals remains a distraction throughout the film. The animals themselves, especially the central Paul-panther, cannot help but remove the viewer from the narrative out of sheer concern and sympathy for the real-life animal’s treatment. The panther looks scared, angry, and nervous, and the pathetic size of the New Orleans Zoo animal pens (a studio set) appears far too small. Admittedly, Oliver mentioned the zoo needs an upgrade and hasn’t been improved since 1942 (the release year of the original film), and he protests the conditions with his superior. But the animals used in the film undoubtedly had to endure small enclosures and prodding treatment to capture the intended result. Clever cutting around a sedated animal (its paw visibly twitching throughout) is used during an autopsy sequence, which seems like an unnecessary risk to take. Anyone with an ounce of sympathy for the treatment of animals will find the film difficult to endure for that aspect alone.

In any case, much like Carpenter’s The Thing, this film gets slimier and bloodier than the viscera-less original. The cat people transform in well-lit rooms, leaving gobs of fur and semi-translucent flesh bits behind, like a gooey snakeskin—perhaps as a way of competing with makeup artists like Rick Baker and Rob Bottin, and their popular werewolf transformations of the time. The special FX remove any doubt of the physical transformation; whereas, some scholars argue that the hinted transformations in the original film took place entirely in the mind of the protagonist. There can be no doubt here, as Schrader intends to draw connections between unbridled sexuality and animallike tendencies (the film’s tagline: “An erotic fantasy about the animal in us all”). Thematically, the transformations prove externalizing as well. Irena in the original tries to remain herself by suppressing her desire; but in the remake, Irena and Paul unleash their desires to become their natural selves.

Moreover, Schrader has changed the story’s sexual underpinnings in demented ways, making the film about sexual desire and repression, but also incestuous impulses. Paul’s preoccupation with cat people mythology finds him seeking to quell his incestuous lusts with unfortunate victims. When he picks up a random woman, he suffers a bout of erectile dysfunction; but a moment later he becomes aroused again when she promises, “Mama will make it better.” Elsewhere, when Irena finally decides to make love with Oliver, everything seems fine at first. A moment later, after Oliver has fallen asleep, she transforms. An animal bursts from underneath her skin in a gory mess. But rather than kill Oliver as Paul said she would, she leaps out of the window and finds herself cornered on a bridge. She leaps off the bridge and makes her way to Oliver’s lake house. He meets her there. They make love once more, but in a stroke of bondage, Oliver ties her down this time in anticipation of what will come next. The final scene takes place much later and finds Oliver and Alice romantically linked, while the New Orleans Zoo has a brand new panther on exhibit, and it’s particularly fond of Oliver.

Setting aside the curious notion of Oliver de-monsterfying Irena through a sadomasochistic sex act, Cat People‘s thread of sexual perversity nonetheless plays like a fascinating subject of psychological and supernatural scrutiny. The film is about maintaining and losing sexual control. Paul has lost complete control and degenerated to the point where his lusts supersede laws against incest. Irena has grown so fearful of her sexuality that it requires bondage and, finally, to be caged like an animal. Schrader is no stranger to films about sex addiction and suppression. He wrote Taxi Driver (1976), whose hero Travis Bickle certainly had a troubling relationship with sex. He also made Auto Focus (2002), a biopic about Hogan’s Heroes star Bob Crane, whose unsolved murder in an Arizona motel surely involved his sex addiction. He’s made two excellent films about male prostitutes with American Gigolo (1980) and The Walker (2007), and let’s not forget Hardcore (1979), in which George C. Scott must traverse the seedy underworld of the L.A. porn industry to find his daughter.

Schrader’s own obsessions cannot help but emerge, proving both exploitative yet thoughtful. Corny double entendres such as Ollie telling Irena to let “that sucker slide right down your throat” while eating oysters, or how panthers should get “a few bones now and then,” result in lowbrow innuendo. Similarly, his use of nudity alternates between objectification and empowerment. Indeed, the sexual politics of bringing the cat people out of the shadows has unfortunate consequences. Take the scene from the original when Alice leaps into the pool in a one-piece bathing suit to hide from a mysterious noise. In the 1942 version, Alice believes she’s being haunted by an animal, probably Irena in cat form, and it will, therefore, fear water. In Schrader’s hands, Alice thinks she’s being hunted by an escaped panther, and being a zookeeper, she should know that panthers can swim. Moreover, Schrader makes O’Toole topless for the scene, reducing the moment to another in a long line of horror scenes involving a nude, vulnerable woman.

In typical remake fashion, Schrader and Alan Ormsby’s script contains a surprising number of kitschy references to the 1942 version that seem like common practice in remakes today, though perhaps not in 1982. But given the changes to the narrative elsewhere, the references seem superfluous, even nonsensical. Take the appearance of the mysterious Cat Woman in a bar who asks Irena, “Mi hermana?” (“My sister?”). The original’s parallel moment hinted that other cat people might exist in the world, thus carrying implications for the remainder of the picture. But Schrader’s version has already established this fact in the prologue (and by introducing Paul). Similarly, Oliver attacks the were-cat Paul with a T-frame in a later scene, recalling a moment when the original’s Oliver and Alice, who were drafting artists, were attacked in their office. The T-frame represented a pseudo-crucifix in the original, while here it seems like a meaningless detail. Also, watch for the countless appearances of cats, cat food, and cat-related cartoons in the backdrop of most scenes. Schrader has counterbalanced the film’s darker mythologizing with an odd sense of humor about everything onscreen, as if he knows it’s absurd.

Cat People earned a small profit, not enough to be considered a success, and its reviews were mixed at best. But time has been kind to Schrader’s film; his approach is psychologically complex and most effective when he embraces an atmosphere of mysticism and vibrant sexuality of a city in which anything can happen. Moreover, there are many individual moments of greatness throughout. There’s a marvelous shot, perhaps the best in the film, where a mid-transformation Paul, his eyes glowing, enters the shadows. The shot looks down from high in the room, and as the camera descends, moving with Paul, the seemingly unbroken take reveals a fully formed panther emerging from the darkness on the other end. Schrader incorporates subtle moments such as this throughout Cat People, as though he and cinematographer John Bailey experimented for every sequence, as opposed to approaching the entire film with a complete vision in mind. The result feels like a patchwork of technical flourishes applied to a story that cannot help but draw our empathy. Incest and sadomasochism aside, who has not felt some sexual anxiety before? Kinski, Heard, and McDowell keep the viewer invested throughout the film’s more eyebrow-raising oddities, whereas Schrader’s approach remains inconsistent but somehow always engrossing.

Sources:

Jackson, Kevin, editor. Schrader on Schrader. Revised Edition. Faber and Faber Limited, 2004.

Kouvaros, George. Paul Schrader. University of Illinois Press, 2008.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review