Castle in the Sky

By Brian Eggert |

Hayao Miyazaki wanted his third feature-length animated picture, named Laputa: Castle in the Sky, to entertain “elementary school-age children” with a simple and exciting story. To be sure, the 1986 film reflects the Japanese master animator’s intentions both in style and structure. The story has incredible momentum and nonstop adventure throughout, nodding to various storybook inspirations as the plot unfolds. Visually, however, the outcome feels reduced to mere anime, as opposed to the innovative animation style that Miyazaki’s work usually presents. But within his self-imposed limitations to the medium, Miyazaki’s anime aligns with his other work themes and all, and far surpasses the output of typical anime directors in scope and vision. That the film compares to more classic forms of anime and avoids novel or free-thinking animation on the part of its creator was an intentional choice, as Miyazaki’s original proposal notes suggest. He sought to “help resurrect traditionally entertaining manga- or cartoon-style films.” Accordingly, the film’s characters have massive eyes and tiny mouths, which might grow as big as their entire head should they laugh or shout loud enough. There’s less commentary than there is action, and the visuals feel less like art and more like an attempt to keep children attentive. Even still, adults should have no trouble getting involved, even if it’s youngsters who Miyazaki wants to entertain.

As always, the exact setting of Miyazaki’s film is difficult to identify, rendering it universal in its ambiguity. The mining town in the opening scenes, where pseudo-European farmers and miners dress in plain and functional clothing, should indicate an Anglo atmosphere circa the 1910s. While in the United Kingdom researching his script, Miyazaki planned on setting the film in post-industrial England, but when that idea was scrapped, the coal miner strikes in Wales influenced his story nonetheless. Labor movements became a crucial part of the narrative, and since such trends have largely faded from Japan, Miyazaki no doubt took inspiration from the rugged cohesion of Wales’ labor force. Miyazaki avoids clear signifiers of time and setting, despite designing his film’s pseudo-Celtic culture from the mining culture of Wales. He juxtaposes varied clothing styles and technologies as non-indicators representative of an alternate world. Automobiles and trains suggest an early twentieth-century time frame, whereas massive airships appear more elaborate and advanced than anything this world has yet known (no wonder Jules Verne is one of Miyazaki’s favorite authors). Technology here does not disappear into the backdrop, as with today’s society where the latest gizmo is just another in a long line. Rather, each new invention is met with wonder and awe, while also appearing without the sheen of an auto-factory, rather the craftsmanship of human hands.

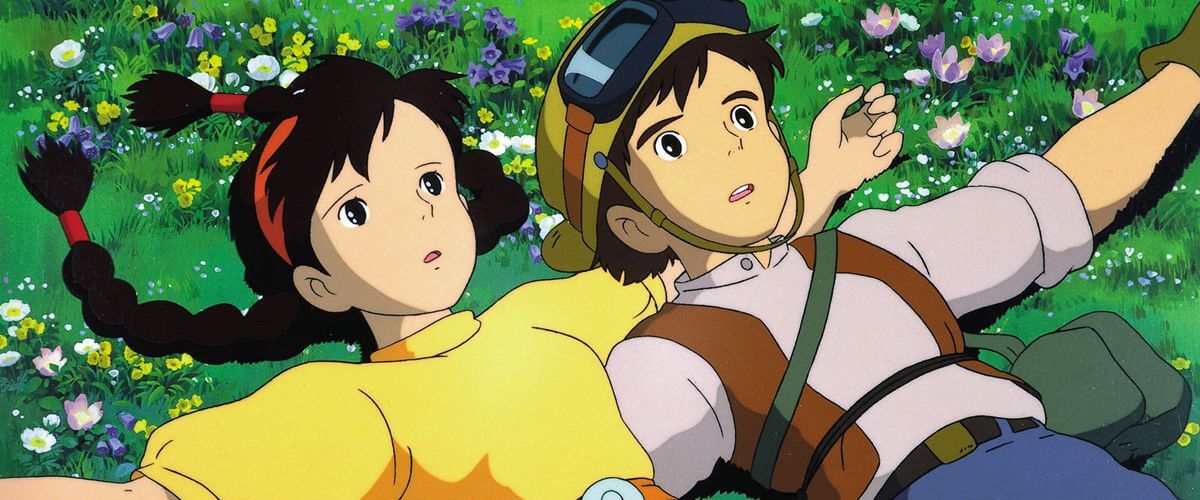

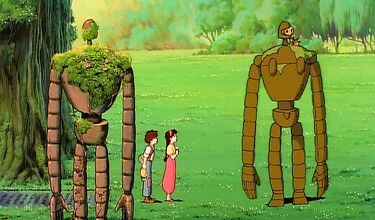

The story opens when a lowly mine-working boy, Pazu, sees something falling from the sky at a feather’s pace. He discovers that a girl, Sheeta, has a special crystal that allows her to hover when she’s falling and that villainous types are after her to unlock the crystal’s hidden powers. First there’s the rowdy-but-lovable gang of sky pirates and their leader Mama Dola. The pirates eventually join up with Pazu and Sheeta against an army, led by the villainous military leader Muska, who has a special connection to the crystal. This is the single Miyazaki film where the villain has no redeemable value—Muska is evil, pure and simple. The conflict is more undemanding because of his absolute wickedness; this makes for great entertainment, but not dynamic storytelling. Everyone’s desperate to get their hands on Sheeta’s crystal, which according to myth comes from a castle in the sky called Laputa. A sort of Atlantis for the clouds, Laputa boasts futurist technologies only dreamed of in tall tales. Pazu’s absent father obsessively traced those legends, so our hero feels personally involved to continue his father’s quest. The crystal leads them to a floating palace that long ago housed the planet’s most ingenious culture, but through technology they destroyed themselves. What remains are inoperative robots and mysterious pathways that spark the protagonists’ imagination. Of course, the villains arrive in the final moments for an elaborate and exciting showdown. Good triumphs and the temptation of technology is driven into the ground.

The story opens when a lowly mine-working boy, Pazu, sees something falling from the sky at a feather’s pace. He discovers that a girl, Sheeta, has a special crystal that allows her to hover when she’s falling and that villainous types are after her to unlock the crystal’s hidden powers. First there’s the rowdy-but-lovable gang of sky pirates and their leader Mama Dola. The pirates eventually join up with Pazu and Sheeta against an army, led by the villainous military leader Muska, who has a special connection to the crystal. This is the single Miyazaki film where the villain has no redeemable value—Muska is evil, pure and simple. The conflict is more undemanding because of his absolute wickedness; this makes for great entertainment, but not dynamic storytelling. Everyone’s desperate to get their hands on Sheeta’s crystal, which according to myth comes from a castle in the sky called Laputa. A sort of Atlantis for the clouds, Laputa boasts futurist technologies only dreamed of in tall tales. Pazu’s absent father obsessively traced those legends, so our hero feels personally involved to continue his father’s quest. The crystal leads them to a floating palace that long ago housed the planet’s most ingenious culture, but through technology they destroyed themselves. What remains are inoperative robots and mysterious pathways that spark the protagonists’ imagination. Of course, the villains arrive in the final moments for an elaborate and exciting showdown. Good triumphs and the temptation of technology is driven into the ground.

The castle itself derives its shape from an inspired mixture of M.C. Esher, classic fairy tale imagery, and the ruins of ancient civilizations all wrapped up into a single construct. Miyazaki borrowed the idea for Laputa from the floating island from the third section of Gulliver’s Travels, but its winding staircases and mysterious pathways are pure Esher. The stony exterior recalls the ruinous remains of an ancient Egyptian or Mayan temple, with large statuesque guardians (in this case broken down robots half-covered in climbing vines) standing guard. An amalgamation of past and future technologies, combined with some fantastical fiction, the castle represents the ideologies of the past and the potential dangers of the future, a common theme in Miyazaki’s work from Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind to Spirited Away.

A mild disappointment in its Japanese release, Castle in the Sky was not imported to the West in a wide format until 2003 with Disney’s home video distribution. The name “Laputa” means a ‘woman of easy virtue’ in Spanish, so the distributors dropped that portion of the title for the large percentage of Spanish speakers in American audiences. Voice talents of Anna Paquin, James Van Der Beek, Cloris Leachman, and Mark Hamill were assembled by John Lasseter, who oversaw the dubbing of each Miyazaki-Disney venture. And along with a hearty dose of time, the film has grown in notoriety over the years. Lasseter maintains that it’s his favorite Miyazaki film, whereas this critic thinks quite the opposite.

A mild disappointment in its Japanese release, Castle in the Sky was not imported to the West in a wide format until 2003 with Disney’s home video distribution. The name “Laputa” means a ‘woman of easy virtue’ in Spanish, so the distributors dropped that portion of the title for the large percentage of Spanish speakers in American audiences. Voice talents of Anna Paquin, James Van Der Beek, Cloris Leachman, and Mark Hamill were assembled by John Lasseter, who oversaw the dubbing of each Miyazaki-Disney venture. And along with a hearty dose of time, the film has grown in notoriety over the years. Lasseter maintains that it’s his favorite Miyazaki film, whereas this critic thinks quite the opposite.

In part, a reaction to the adult themes overtaking his previous effort and first all-Miyazaki film, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, the intended ease of Castle in the Sky presents a lesser experience than other Miyazaki works. The majority of the director’s output seems grounded in making animation appeal to adults and children simultaneously, and yet here the scale tips perhaps too much to the younger demographic. This was his Treasure Island, being a story wherein through an impossible adventure a young male hero grows from his experience, thus inspiring other youngsters to think about adventure more actively as a reader or viewer. Children lose themselves in Miyazaki’s exciting chases and grandiose imagery, meanwhile, adults have only the same to cling to—and only a minor environmentalist, anti-technology theme gives the otherwise wholly escapist picture depth.

But even a mediocre Miyazaki film is a great movie by any other standard. Compare Castle in the Sky to Walt Disney releases in the 1980s—like The Black Cauldron or Oliver and Company—and really there is no comparison at all. Mizayaki’s imagination far exceeds that of his contemporaries, and the result derives from an individual writer-director renders the final film more singular in its expression, whereas Disney movies have a tendency to become muddled from their collaborative construction. Miyazaki’s characters feel tangible and human, his action scenes ripe with energy, and his film’s design, as always, abundantly imaginative. That there’s little to analyze in the subtext is only a minor flaw when compared to the film’s escapist grandeur.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review