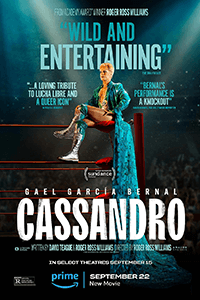

Cassandro

By Brian Eggert |

(Note: Distributed by Amazon Studios, Cassandro opens theatrically in limited release on September 15, 2023, and drops on Amazon Prime Video a week later.)

Traditional lucha libre wrestling usually features beefy men masquerading in shiny masks and pummeling each other in the ring. The luchadors embody the sheer muscle-bound machismo of this popular Mexican sport, and classical conflicts and extreme personalities mark its high drama. Exóticos occupy a counterpoint to the luchadors, presenting as flamboyant jesters in drag who taunt their opponents and incur the homophobic slurs of the crowds. The idolized luchadors always win against the exóticos, thoroughly defending their manliness, except in the case of Cassandro, an El Paso native who entered the lucha libre scene in the late 1980s. An openly gay wrestler known as the “Liberace of Lucha Libre,” Saúl Armendáriz defied the sport’s dynamics, stereotypes, and prejudices to become the first exótico to win matches and be celebrated by the masses. Cassandro is a rather sanitized and respectful biopic about the icon, featuring an energetic and moving performance by Gael García Bernal. Although a warts-and-all portrait may have been preferable to confront some of the darker chapters in Saúl’s life, the competent and winning film should charm the uninitiated.

The film introduces Saúl at a modest wrestling match performed in a warehouse connected to an auto shop. He already appears in his signature blond hair with close-cropped sides, his stature diminutive, suggesting that Bernal was perfectly cast in this role. Surrounded by human slabs twice as tall and three times as wide as him, Saúl performs as El Topo (The Mole), “the abominable creature of Madrigal Street.” A runt whose squirrely role in the ring is to annoy and then lose to the bigger guys, Saúl knows the game is rigged against him. When he faces off against Gigántico (played by a real-life Mexican wrestler known as Murder Clown), he hopes to change that: “Let’s give them a show. Follow my lead,” he says. But the luchadors adhere to traditions, and they’re not willing to give up their masculine, zealously hetero identity for Saúl’s dreams of showmanship. Defeated, Saúl grows disenchanted that there’s no “poetry” among the winners—a luchador flat-out tells him, “Don’t fuck with [the traditions of] lucha libre”—whereas exóticos have all the flashy outfits and theatricality he admires.

Nevertheless, Saúl finds inspiration from the women in his life. His supportive mother (Perla de la Rosa) feeds his stagecraft, contributing to his love of drama through their shared affection for the early ’90s telenovela Kassandra and leopard-print garments from her closet. Saúl also improves as a wrestler with the help of Sabrina (Roberta Colindrez), a trainer who agrees to develop his natural skill. By contrast, he receives little support from the men in his life. Saúl does not speak to his estranged father (Robert Salas), who has another family somewhere. Similarly, his secret lover, a luchador known as El Comandante (Raúl Castillo), maintains a family and refuses to come out of the closet, fearful of repercussions from the homophobic culture that surrounds lucha libre. So part of Saúl’s journey—first to debut his new character named Cassandro, second to make Cassandro a victorious hero who earns the audience’s favor—means overcoming his hangups and being himself, focusing on how good it makes him feel versus how the audience reacts. In turn, his singular presence makes him a star.

Director Roger Ross Williams handles the material straightforwardly and sentimentally, and without a hint of irony—though, there’s potentially another version of this story that goes full camp. Doubtless, Williams felt close to the subject, having also made a short documentary about Armendáriz called The Man Without a Mask for the series The New Yorker Presents in 2016, which offers a more granular look at the wrestler, despite its brief runtime. The screenplay by Williams and David Teague glosses over some of the more troubling chapters of Saúl’s life referenced in the doc, such as the assault that inspired Saúl to learn to defend himself or his self-destructive streak, including substance abuse and a suicide attempt. With a prolific career in television and documentaries, the director plays it safe behind the camera, delivering what feels like the Bohemian Rhapsody (2018) of wrestler biopics, complete with a delicate and stirring score by Marcelo Zarvos and clear-eyed cinematography by Matias Penachino.

Director Roger Ross Williams handles the material straightforwardly and sentimentally, and without a hint of irony—though, there’s potentially another version of this story that goes full camp. Doubtless, Williams felt close to the subject, having also made a short documentary about Armendáriz called The Man Without a Mask for the series The New Yorker Presents in 2016, which offers a more granular look at the wrestler, despite its brief runtime. The screenplay by Williams and David Teague glosses over some of the more troubling chapters of Saúl’s life referenced in the doc, such as the assault that inspired Saúl to learn to defend himself or his self-destructive streak, including substance abuse and a suicide attempt. With a prolific career in television and documentaries, the director plays it safe behind the camera, delivering what feels like the Bohemian Rhapsody (2018) of wrestler biopics, complete with a delicate and stirring score by Marcelo Zarvos and clear-eyed cinematography by Matias Penachino.

Even so, it’s a pleasure to watch Saúl meet people like Lorenzo (Joaquín Cosío), who seems like a shady promoter at first—and perhaps he is—but he delivers when it comes to arranging a match in Mexico City against the Son of Santo (playing himself). Flashbacks to Saúl’s childhood show him and his father watching the Amazing Santo wrestle, building to the moment when Cassandro steps in the ring with Son of Santo. Usually, Cassandro might taunt his opponent with queer-coded, sexually suggestive behavior. But the match shows two masters who quickly learn to respect each other for their ability to entertain, to the extent that the winning becomes secondary to the show, with Cassandro conceding to the champ. In this sense, Williams and Teague have written a scenario similar to Rocky (1976), where victory is less the point than defying expectations and earning the crowd’s approval.

In the wrestling scenes, Bernal impresses by performing many of the stunts and moves himself, nimbly bounding around the ring, climbing on the ropes, and taking hits. Surely, stuntmen were used, but the actor and team of editors sell every moment of the preordained matches, which represents a change in attitudes toward exóticos. More important for Cassandro is the theme about being yourself, even when people shout hateful words from the stands, even when the system seems rigged against you. Cassandro inspired young men to come out and search for acceptance with their fathers, even while, in the film, he rises above his daddy issues. Unfortunately for Cassandro, Williams’ doc suggests a far more complex character, somewhat reminiscent of Darren Aronofsky’s The Wrestler (2008), where his relationships aren’t so tidily contained within Screenplay 101 archetypes. Still, the dramatic feature, which debuted at Sundance and will live on Amazon, makes for an inspiring tale.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review