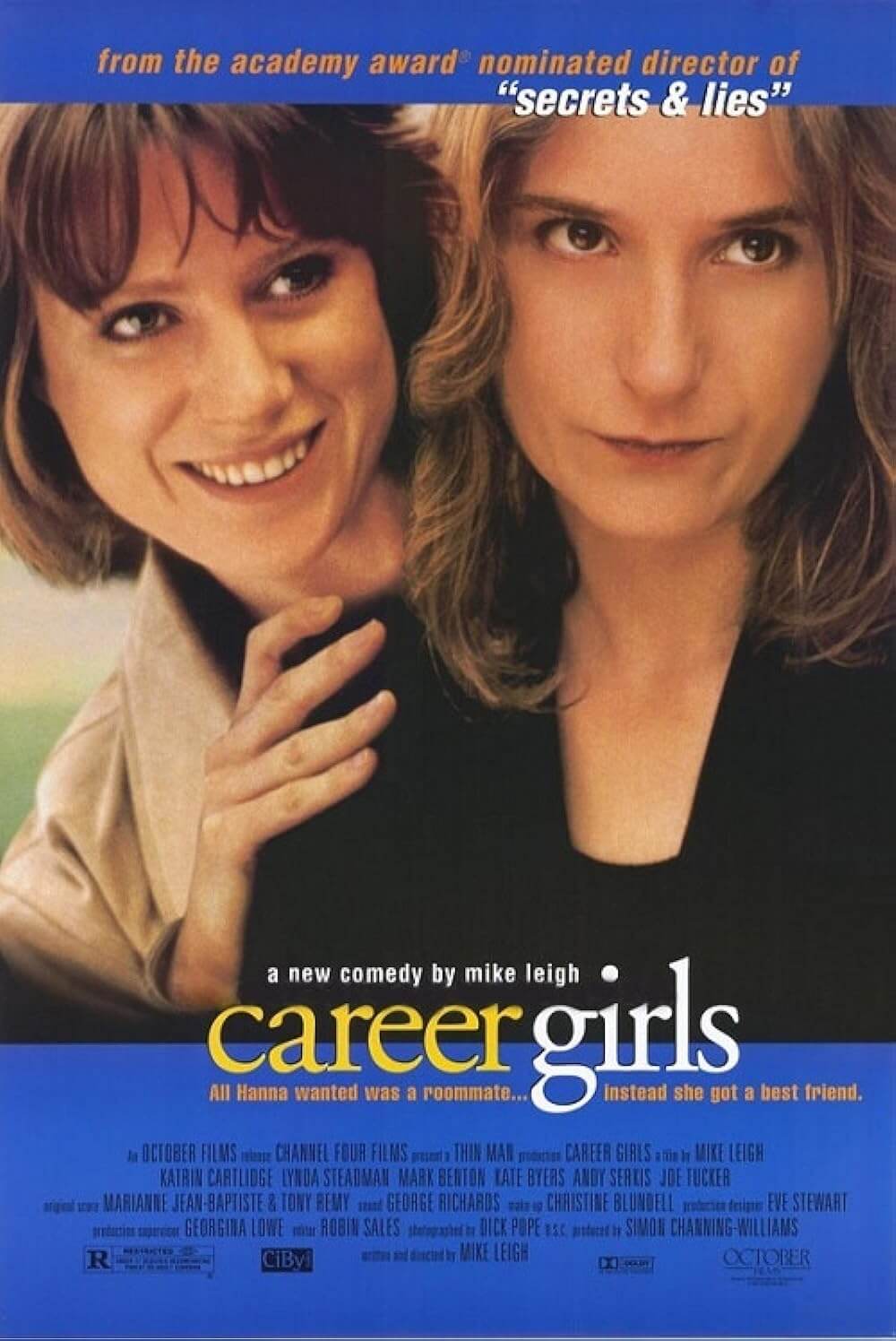

Career Girls

By Brian Eggert |

A film that marks a transition in the career of British director Mike Leigh, Career Girls links the two predominant strains in his work: his earlier tendency for realistic portraits of working-class people, whom he sometimes treats as caricatures; and his later work, which is more reflective and deals with matters of history, memory, and time. In the former category, you have the grimily realistic, albeit exaggerated, personalities in Life Is Sweet (1990) or Naked (1992)—films about people who struggle in their present circumstances. In the latter category, you have period dramas such as Topsy-Turvy (1999) and Mr. Turner (2014), whose characters deal with the passage of time, the scope of their lives, and their role in history.

Career Girls stars Katrin Cartlidge as Hannah, a woman returning to London for the first time in years to visit her college roommate Anna, played by Lynda Steadman. Both are now successful business people, outwardly well-mannered and dressed in nondescript tan clothes—veritable symbols of the modern workaday woman. But a decade earlier they were college students garbed in shabby punk gear, sporting greasy hair, unhinged emotions, and listening to the ever-present sounds of The Cure. We see these images of the past through Hannah’s memory as she recalls her introduction to Anna as a hurtful one.

In her youth, Hannah carries the scabs of dermatitis on her face; she can’t look people in the eye, and when she speaks, she does so with an odd click of her neck that makes her head look off-kilter. The younger Anna was no better: she smacks herself as a punchline, and she’s full of biting comments and an insensitive cruelty. When they get together in the present day, they initially clash, just as they did when they first met so many years ago. But as the film progresses, and Hannah keeps recalling aspects of her friendship with Anna, the present-day relationship deepens just as their friendship in the past does. The emotional bond between the two friends reveals itself to be profoundly close.

As serious as this might sound, Career Girls has the streak of humor that finds its way into many Leigh films. Watch the comic scene when Hannah accompanies Anna to look for a flat. They visit a posh apartment owned by a sleazy Andy Serkis (better known as Golem), and Anna remarks, “I suppose from up here you can see the class struggle.” Later, they visit another flat for sale, and the real estate agent turns out to have been a former lover in an odd, sitcom-esque coincidence. Indeed, there’s a strain of coincidence running through the film, which Leigh openly acknowledges in the dialogue. Sometimes the coincidences are played for laughs; sometimes they’re tragic. When they visit their former college stomping grounds and happen to find an old friend, Ricky (Mark Benton), still in the area, the coincidence underscores that time is not always kind (in a scene recalling the sequence with the homeless man in Happy-Go-Lucky). Hannah and Anna’s reaction to Ricky’s situation is tender enough to induce tears.

Career Girls is a different kind of Leigh film, not only for the division of its themes but also for the formal ways in which the director balances them. Leigh is known for long shots that focus on a conversation or scene for several minutes, allowing the viewer to feel immersed in the moment, which feels even more realistic because of his limited use of the cut. But here he uses editing in a much more active way. He’s intercutting between the past and the present, creating an association between the two through editing. This approach is an apt metaphor for the film itself, and the way it links Leigh’s past work with his predominant style in the years to come.

(Note: This review was originally posted on Patreon and moved to Deep Focus Review in February 2020.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review