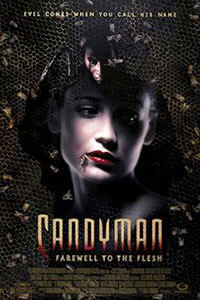

Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh

By Brian Eggert |

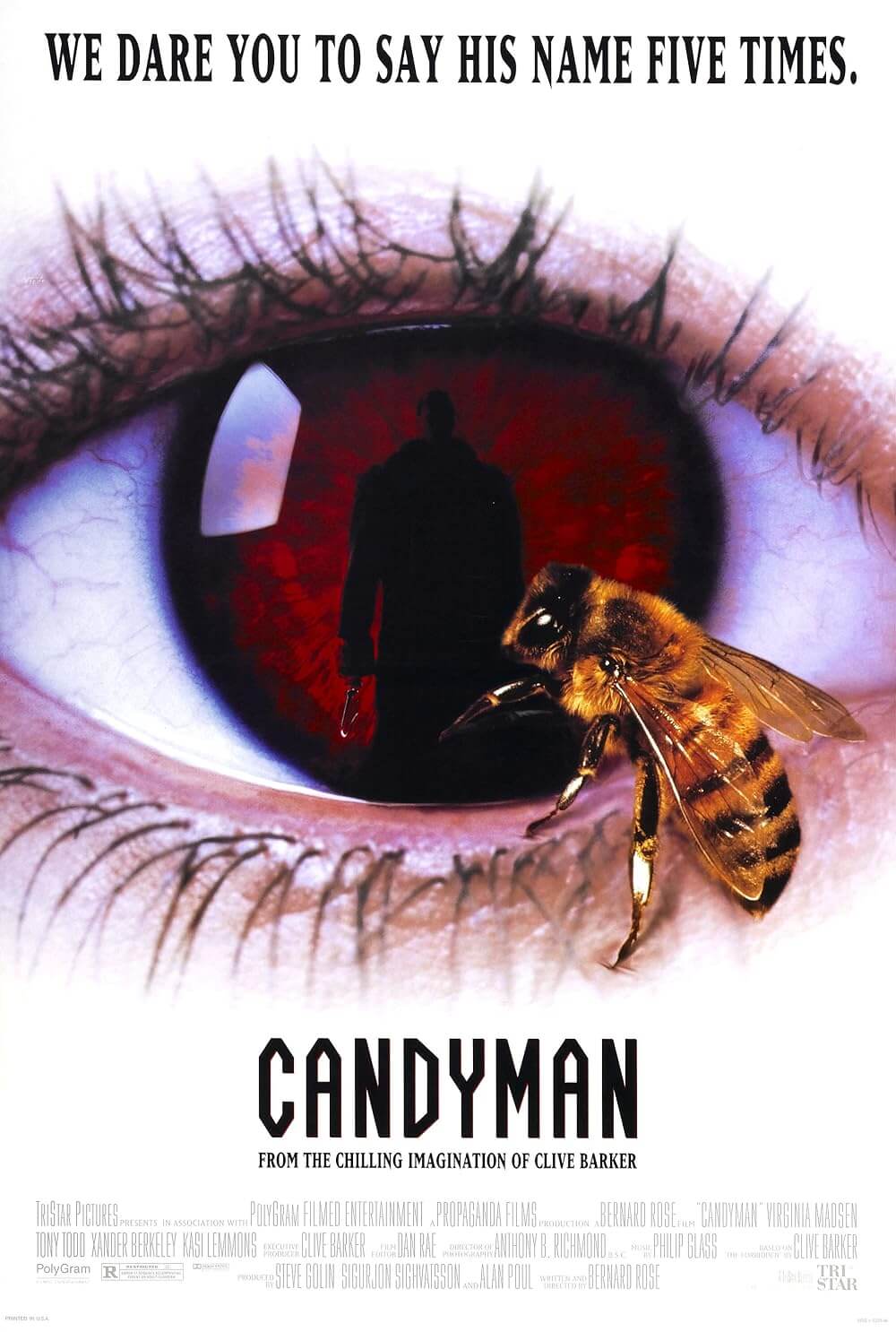

Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh opens with a pre-credits hook, if you’ll forgive the pun. The smarmy Cambridge academic from the original film, Professor Purcell (Michael Culkin), gives a lecture in New Orleans to promote his new book about the Candyman myth, which he conveniently recounts. A Black man who was brutally murdered by a racist mob after he fell in love with a white woman returns as an urban legend, slaughtering those who dare say his name five times in the mirror. Then, someone in the audience challenges Purcell to do just that. When he does, a wretched hook bursts through a projector screen and attacks Purcell, causing his audience to leap in their seats. But it’s just a trick, a bit of showmanship designed to sell Purcell’s book. Candyman kills him later for real, of course. However, the fake-out is a perfect example of what’s wrong with this sequel. It’s a work of horror filled with serious issues about confronting America’s racist past, but it’s made with cheap jump-scares and afflicted by a bad case of sequelitis.

Although the original film, based on a story by Clive Barker, received a thoughtful treatment by director Bernard Rose, The Powers That Be rejected Rose’s idea for a follow-up—a Candyman origin story about a doomed interracial couple. Instead, the filmmakers made a typical horror franchise maneuver by telling the same story over again, albeit with a new protagonist and a new location. The sequel, directed by Bill Condon, places another doubting white woman in charge of unraveling the origins of the Candyman myth, only to learn she has a profound personal connection with him. Annie (Kelly Rowan) is a New Orleans school teacher who summons Candyman when she tries to convince her class that he doesn’t exist. Much like Virginia Madsen’s character from the original, Candyman kills people close to Annie. The police suspect her, but they also suspect her troubled brother Ethan (William O’Leary). Years earlier, their father died in a manner attributable to Candyman. More recently, Ethan is suspected of killing Purcell.

The setting gives the movie character. It takes place in the days leading up to Mardis Gras, which is evident not only by the masked parties that occupy the backdrop but the persistent gabbing of a radio announcer. In a disembodied voice reminiscent of Wolfman Jack, who died the same year as the sequel’s release, a disc jockey prattles on about the delights of Carnival even when no radios are in sight. It’s a strange aural connective tissue from scene to scene, and even stranger because the announcer never plays music. Instead, Philip Glass once again supplies the score, but his music is less mythical. His score in the original elevated the story to considerable heights, but here, when he punches the keys of his electric organ throughout the climax, it sounds like he’s orchestrating a cheap Dracula movie.

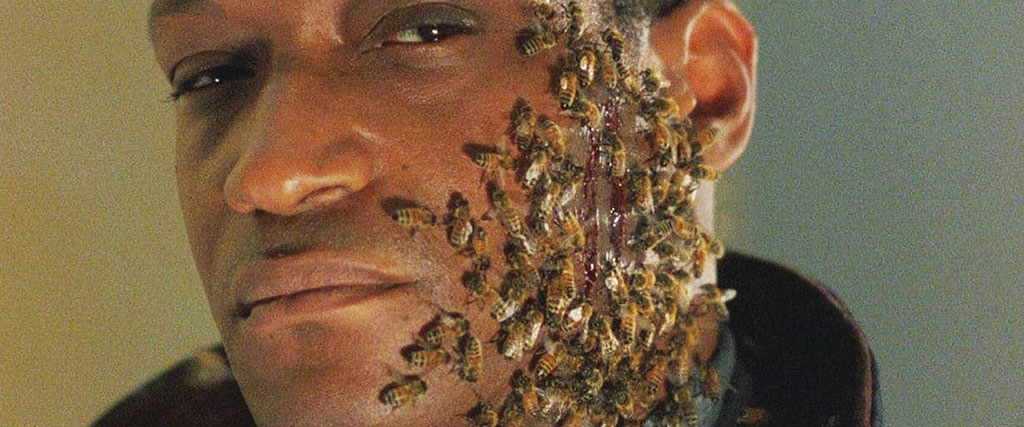

Similar to other horror franchises, the Candyman movies have an inconsistent mythology. Alas, Farewell to the Flesh isn’t half as fun as the deviations in A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge (1985). The original described its boogeyman’s origin story as a tragedy that befell a well-educated artist who was confronted by racists. The sequel offers a different explanation: Candyman, again played by Tony Todd, is now a slave named Daniel Robitaille. He impregnated a white woman, and so a plantation mob sawed-off his hand and spread honey on his body, at which point a freak swarm of bees attacked and stung him to death. The child, as it turns out, was Annie’s ancestor. (Now ask yourself, why is Candyman killing Annie’s family members, who are also his descendants?) This twist leads to some interesting possibilities, none of which screenwriters Rand Ravich and Mark Kruger are up to exploring with any depth.

For instance, Candyman’s new history as a slave could have been a way for the filmmakers to address the historical violence against African Americans in the United States. Sure, there’s a gruesome flashback where a mob violently attacks Robitaille, chanting “Candyman”—a mocking name given to him because of the honey they use to attract the bees. But the scene comes in the last few minutes of a movie that spends most of its runtime establishing Candyman as a relentless specter worthy of our fear rather than a victim of racial persecution deserving of our empathy. The movie also could have done more with Annie’s mother, played by Veronica Cartwright, who suppresses these details about the family’s past out of racist shame. If the sequel seems to have matters of race, slavery, and retribution on its mind, why does it feel like it has nothing to say about them?

Individual elements stand out, such as Todd’s performance. The look he gives Annie when he remembers his past and asks her to “Be my witness” is heartbreaking. The fact that Madsen’s character from the original was consumed by fire like a witch, where the waters cleanse Annie in a flood, is also a detail worth noticing. Then again, the climactic scene, where Candyman’s curse is broken by the shattering of a mirror, ends the movie on a laughable note of bad 1990s CGI when Candyman collapses into a thousand digital shards. No matter the situation, Condon seems to take each scene as seriously as the last, regardless of whether he’s slicing and dicing Candyman’s victims in a display of blood and gore or he’s addressing American racism. It’s all shot in the same “Gotcha!” tone, diminishing the movie’s substance with shocks worthy of a haunted house experience.

The problem is, Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh isn’t scary, and when it attempts to be, we find ourselves frustrated by the filmmakers’ lack of interest in figuring out the story’s central folklore. Candyman deserves our empathy. And if he was killing only the people responsible for his death, that might make him a horror antihero. Still, the filmmakers allow the character to kill indiscriminately, whereas Candyman’s actions in the original had a specific intended outcome: to make Madsen’s character experience his pain. What motivates him to kill in the sequel? Has the process of becoming a myth left him angry at the world and willing to kill anyone, even in his own bloodline? The more this sequel reveals about Candyman’s past, the less his actions make sense, and the less we care about what happens. Much like other horror franchises from Halloween to A Nightmare on Elm Street, which continued to shed light on the resident monster’s past with each new sequel, Farewell to the Flesh’s attempt to demystify Candyman robs him of his power.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review