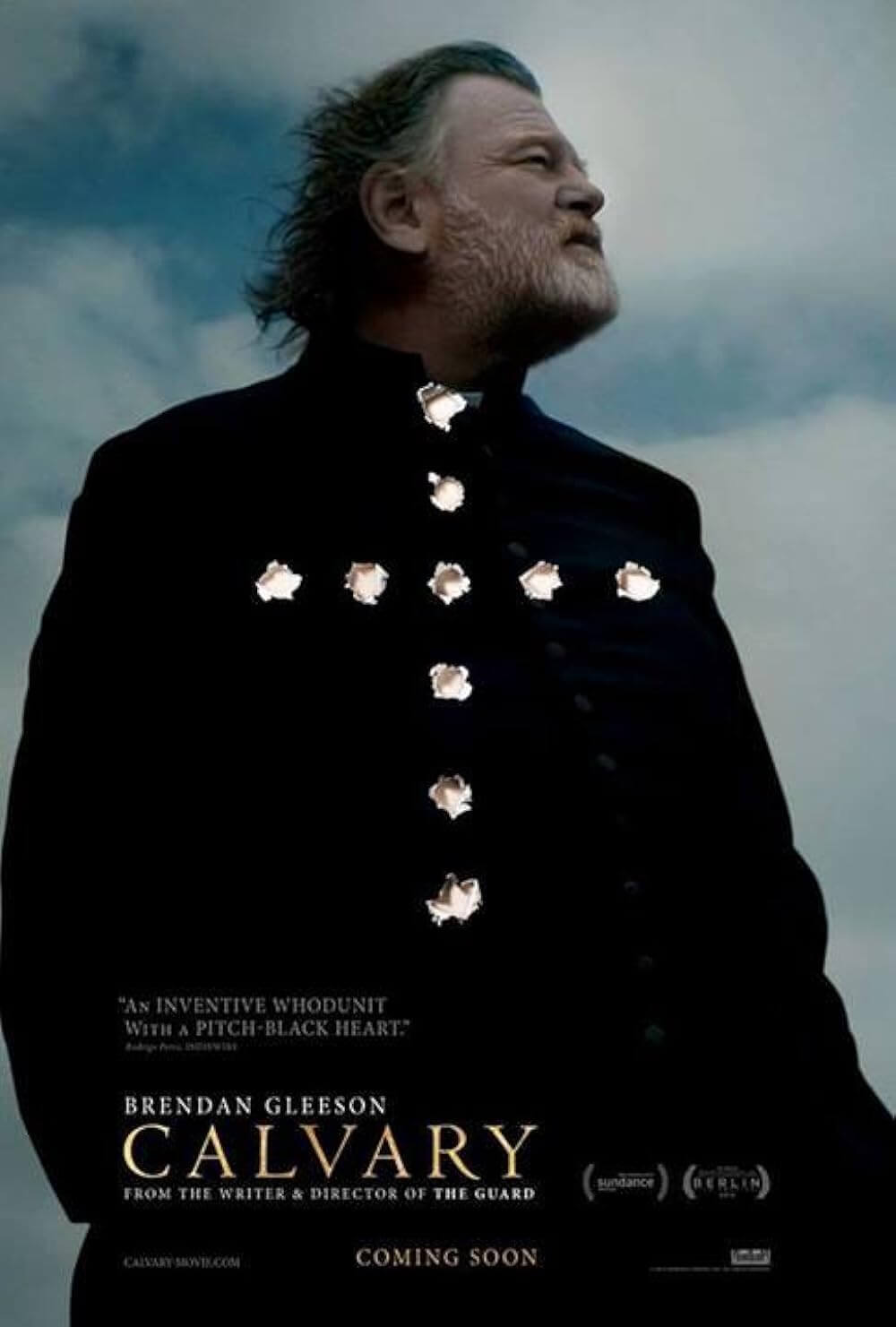

Calvary

By Brian Eggert |

A priest in a small Irish town, Father Lavelle, played by the inimitable Brendan Gleeson, awaits a confessor. A man enters off-screen and says, “I was 7 years old when I first tasted semen.” He proceeds to tell Lavelle about his abuses and torture as a child at the hands of his parishioner. And then he warns Lavelle that one week from today, on a Sunday, he’s going to murder Lavelle. “There’s no point in killing a bad priest,” he observes. “I’m going to kill you because you’re innocent.” His eye-for-an-eye reprisal will pluck out an innocent just as he was plucked, and therein he will exact revenge not on the individual but on the Catholic Church and its institution of abuse. Anglo-Irish writer-director John Michael McDonagh calls his film Calvary after the name of the hill in Jerusalem on which Jesus was crucified. The proposed killer isn’t out for anything so monumental as crucifixion, however. He tells the tough, yet introspective Lavelle to meet him on the beach. And though Lavelle knows the man, he refuses to call him out or report him, and uses the coming days, as the would-be killer suggests, to put his house in order.

McDonagh’s film follows his 2011 debut, The Guard, which also starred Gleeson, who played a racist action-comedy cop in that film. In Calvary, Gleeson, that towering figure capable of a vast range from The General (1998) to Mad-Eye Moody in the Harry Potter series, appears under a thick gray beard tinged with red, his expressions perfectly attuned to Father Lavelle’s interchanging moments of levity and ferocity, with just the right touches of contemplation, caustic humor, and deeply felt humanism throughout. Much like McDonagh’s brother Martin, who directed Gleeson in a soulful performance for In Bruges, the filmmaker has employed the actor as a muse, and what a muse he proves to be. Gleeson’s performance permeates an incredible weight through his gnarled features, windswept hair, and tender eyes. Trying to imagine another performer rendering Father Lavelle with the same depth of integrity, carrying carefully guarded wounds from a troubled former life (Lavelle is a widower and alcoholic), is nearly impossible. And though Calvary may seem at risk of becoming a one-man show, McDonagh doesn’t identify the man who has threatened Lavelle and instead populates his film with a variety of fascinating suspects and specimens.

The town’s small group of locals, who attend mass every Sunday like good Christians out of some distant cultural obligation, deride Father Lavelle after the services—their faith in the institution long since lost after countless betrayals by the Church. Resident butcher Jack (Chris O’Dowd) may have beaten his promiscuous wife (Orla O’Rourke), though he doesn’t seem to mind that she’s shacking up with the hostile mechanic, Simon (Isaach de Bankolé). An awkward young man (Killian Scott), fed up with his unsuccessful pursuit of female companionship, considers joining the army instead of taking out his aggressions on women. A financial fat-cat (Dylan Moran) has retired to their hamlet and invites Lavelle over to his extravagant home just to mock and boast about his worthless riches. An aged, dying writer (M. Emmet Walsh) seemingly finds his only connection in Lavelle, whereas the belligerent atheistic doctor (Aidan Gillen) uses every opportunity to insult the priest’s convictions.

Though such characterization may seem extreme, there are more polarized characters still. Consider the solemn Frenchwoman (Marie-Josee Croze) who loses her husband in a car accident but retains her faith, or the irredeemable cannibalistic serial killer (Domhnall Gleeson, acting opposite his father) who portends regret amid godlike delusions. None is more affecting than Lavelle’s relationship with his daughter (Kelly Reilly, from Flight, excellent), who arrives in town with bandages around her wrists from a failed suicide. Her long walks with her father on green landscapes and alongside ocean waves crashing against the rocks result in heartfelt conversations that never feel forced or inauthentic within the melancholy—but otherwise sardonic and occasionally hilarious—proceedings. Much of the film consists of long patches of dialogue, broken up only by the occasional church burning, a horrific act of animal cruelty, or barroom scuffle. McDonagh’s cinematic dramaturgy ultimately leads to an indictment of the Church, a curious look at faith, and a complicated deliberation on atonement.

Combining the meditative quality of Robert Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest (1951) and the plot-driven mechanics of Alfred Hitchcock’s I Confess (1953), McDonagh’s Calvary reminds us of each passing day as the coming Sunday grows closer. Some characters in Lavelle’s town make surprising turns as Lavelle interacts with them; others refuse to change and remain their threatening, unpleasant selves. All the while, our dread and the suspense of Father Lavelle’s fate washes over us, not as a thriller does; rather, like a pensive study of a fatalistic protagonist, enhanced by Patrick Cassidy’s forlorn score. Through his sophisticated dialogue and Larry Smith’s simple-but-gorgeous compositions, McDonagh’s treatment of the wise and world-weary Lavelle contains equal measures of sacrificial responsibility and an almost suicidal embrace of The End. But there’s something intensely poetic in Calvary, despite its cutting nature. At times shocking, certainly thoughtful, and tremendously well made, it’s also quite beautiful in its cynical worldview.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review