Reader's Choice

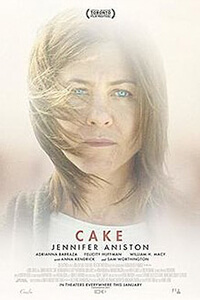

Cake

By Brian Eggert |

Cake is about one woman’s inability to find closure from trauma when her physical aftereffects are a constant reminder of her psychological scars. Although it might’ve been an unflinching portrait of a borderline alcoholic, drug-addicted, grief-stricken woman attempting to numb her emotional trauma and chronic pain, it plays more like an accessible dark comedy, complete with a plucky score and hopeful ending. Released in 2014, it’s meant as a deglamorized showpiece for Jennifer Aniston. She plays a pleasantly unpleasant pain sufferer who, irritable and sarcastic, takes her anguish and anger out on those around her. In Aniston’s serious role and the atmosphere of ruin, Cake wants to be edgy and genuine, to expose raw and visceral feelings. But it keeps from mining the most searing dramatic soil because, given the nature of the tragedy which it orbits, confronting them head-on may prove uncomfortable to audiences.

Jennifer Aniston stars as Claire, a Los Angeles native who lives in the wake of a car accident some time ago, an event whose full consequence, a dead child, is hinted at in small doses as the story unfolds. In the first scene, Claire attends a support group for sufferers of chronic pain, one of whom, Nina (Anna Kendrick), has killed herself by jumping from a freeway overpass. With disarmingly funny sarcasm, Claire refuses to acknowledge her grief, enough to get her kicked out of the group. Claire’s pain, physical and mental, isolates her. Those in her support system, including the rattled support group leader (Felicity Huffman), a fed-up physical therapist (Mamie Gummer), an artificially encouraging doctor (Lucy Punch), and a concerned but separated husband (Chris Messina) try to help, but ultimately keep their distance. Most people who know her call her “fucked up” or the c-word, and she copes with a regular diet of Percocet, Oxycontin, and white wine. Her self-induced detachment is reflected in the repeated presence of a random possum by her pool at night—a creature known to play dead when confronted.

If Claire has a true friend, it’s her Mexican housekeeper, Silvana (Adriana Barraza). While wagging her finger at some of Claire’s life choices, Silvana also serves as Claire’s cook and driver. She’s the heart of the film; it’s her devotion to the protagonist that makes the viewer believe there’s something under the abrasive exterior worth saving. But the screenplay by Patrick Tobin barely explores Silvana, aside from a brief glimpse into her modest homelife and her single gripe about being underpaid. Her character exists in the script because Claire needs someone to love her unconditionally in order to appear sympathetic; without her, the more elusive elements of the plot wouldn’t be enough to keep us invested in Claire’s situation. Silvana, stripped of much agency, remains the doting Other, a troublesome cliché on par with magical black characters or noble savages—tropes designed to help white protagonists achieve their goals and work through their emotional baggage. Meanwhile, Claire, who has seemingly unlimited financial resources, can’t be bothered to give her only friend a raise.

Things start to look up when Claire visits Nina’s home, now inhabited by the widower Roy (Sam Worthington) and his motherless young son, obviously soon-to-be replacements for Claire’s broken marriage and lost child. Both Claire and Roy have been brought to their emotional limit, and both almost immediately see one another as convenient stand-ins for the people they’ve lost. After some encouragement from Silvana, Claire finally sees hope in Roy and resolves to give a damn. She begins to attend physical therapy, makes nice with a few enemies, and even enters her late son’s bedroom for the first time in a long time. But of course, in predictable fashion, just as things are looking up, the story brings Claire down to her lowest of lows, only to bring her back up again—quite literally. Claire spends much of the film riding in cars with the seat fully reclined to assist her back pain. In the final scene, she places the seat upright as a symbol of her newfound determination to embrace life.

Things start to look up when Claire visits Nina’s home, now inhabited by the widower Roy (Sam Worthington) and his motherless young son, obviously soon-to-be replacements for Claire’s broken marriage and lost child. Both Claire and Roy have been brought to their emotional limit, and both almost immediately see one another as convenient stand-ins for the people they’ve lost. After some encouragement from Silvana, Claire finally sees hope in Roy and resolves to give a damn. She begins to attend physical therapy, makes nice with a few enemies, and even enters her late son’s bedroom for the first time in a long time. But of course, in predictable fashion, just as things are looking up, the story brings Claire down to her lowest of lows, only to bring her back up again—quite literally. Claire spends much of the film riding in cars with the seat fully reclined to assist her back pain. In the final scene, she places the seat upright as a symbol of her newfound determination to embrace life.

Director Daniel Barnz—of the modern-day fairy tale Beastly (2011) and the feel-good dramedy Won’t Back Down (2012), about inner-city schools—means well with this indie production. Barnz and Tobin address the underrepresented condition of chronic pain, which can lead to further consequences (drug addiction, etc.). However, the writing here seeps into the dramatically precise and banal. Consider a scene that finds Claire alone, listening to music that evokes a painful memory; she shuts off the music and says to herself, “Enough with the fucking honesty”—ironically enough, an incredibly hollow line. Elsewhere, Claire loses herself in loopy dreams from her pill-popping, but her dreams are the stuff of dull psychoanalysis: fragmentary images that serve as puzzle-pieces into her mental state. Barnz applies a formal competence to the production, primarily due to the lensing by cinematographer Rachel Morrison. Claire’s waking dreams, for instance, adopt subtle color cues from the surroundings, such as the yellow-hued appearance of Nina in a diner with yellow panes of decorative glass.

After epitomizing the 1990s and early 2000s on Friends, Aniston has never had much success shedding her America’s Sweetheart image. Then again, if the omnipresence of lowbrow rom-coms on her résumé is any indication, she’s not interested in changing her image. Every time she appears in something out of the ordinary—like 2002’s The Good Girl, in which she plays an unhappily married grocery store cashier drawn to a new, disturbed employee—she counteracts it with a half-dozen titles from Rumor Has it (2005) to The Bounty Hunter (2010) to Just Go with It (2011). Getting past her frequently poor taste in projects, Aniston glimmers in a few rare examples where she turns down her accessible charm to play moody or beleaguered characters far removed from her usual crowd-pleasing persona. Cake‘s departure seems as though it was engineered for Oscar consideration. Aniston served as an executive producer and, following an aggressive awards season campaign, she was not nominated in the Best Actress category at that year’s Academy Awards. In fact, the film was generally ill-received by critics and audiences if the low scores on Metacritic and Rottentomatoes mean anything.

Since Cake is predicated on its central performance, let’s consider what Aniston is doing here. Read any review from the time of its release, and the critic probably remarks that Aniston was brave for wearing little makeup, unkempt hair, and appearing with a scar across her face. Sadly, the idea of not appearing Movie Star-beautiful is equated with bravery; and worse, certain vain circles would reprimand a performer if they decided to make a public appearance in such a state. Much of her performance seems like Rachel, her character from Friends, on a very bad day. Most of Aniston’s roles seem like variations on Rachel, which is another way of saying that Aniston has more presence than range. Claire is sarcastic and mean, but somehow likable. We can tell she was once a good person but her pain has warped her. Still rather attractive despite downplaying the artifice, Aniston is more effective in later scenes in which Claire breaks into tears or violently confronts the man responsible for her son’s death (William H. Macy, in a role that would have been better suited to anyone without such a recognizable face). Nevertheless, Barraza played a more complex and layered role, even if the filmmakers failed to adequately explore it.

Since Cake is predicated on its central performance, let’s consider what Aniston is doing here. Read any review from the time of its release, and the critic probably remarks that Aniston was brave for wearing little makeup, unkempt hair, and appearing with a scar across her face. Sadly, the idea of not appearing Movie Star-beautiful is equated with bravery; and worse, certain vain circles would reprimand a performer if they decided to make a public appearance in such a state. Much of her performance seems like Rachel, her character from Friends, on a very bad day. Most of Aniston’s roles seem like variations on Rachel, which is another way of saying that Aniston has more presence than range. Claire is sarcastic and mean, but somehow likable. We can tell she was once a good person but her pain has warped her. Still rather attractive despite downplaying the artifice, Aniston is more effective in later scenes in which Claire breaks into tears or violently confronts the man responsible for her son’s death (William H. Macy, in a role that would have been better suited to anyone without such a recognizable face). Nevertheless, Barraza played a more complex and layered role, even if the filmmakers failed to adequately explore it.

Despite its impressive cast and a fine, but hardly daring central performance, Cake has been written and shot as though the filmmakers think they’re creating an elaborate dramatic puzzle. But since the plotting is at times achingly predictable, the structure, which withholds information such as the source of Claire’s pain for almost no added impact, proves as convoluted as the everything’s gonna be all right ending. An indication of how badly Cake miscalculates its appeal occurs during the end credits, when the letters “A” in each name appear turned on their left side. It’s meant as a cute reference to how Claire rides in reclined car seats throughout the film, yet it also trivializes what should be an unflinching detail of her physical and mental states. Given that, we must ask why would members of the cast and crew want a letter in their name turned on its side, especially if that represents Claire at her worst? It’s an odd if inconsequential detail that leaves the viewer perplexed about the filmmakers’ intentions, if not about the credits then for the entire tone of the film.

(Editor’s Note: This review was commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your support!)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review