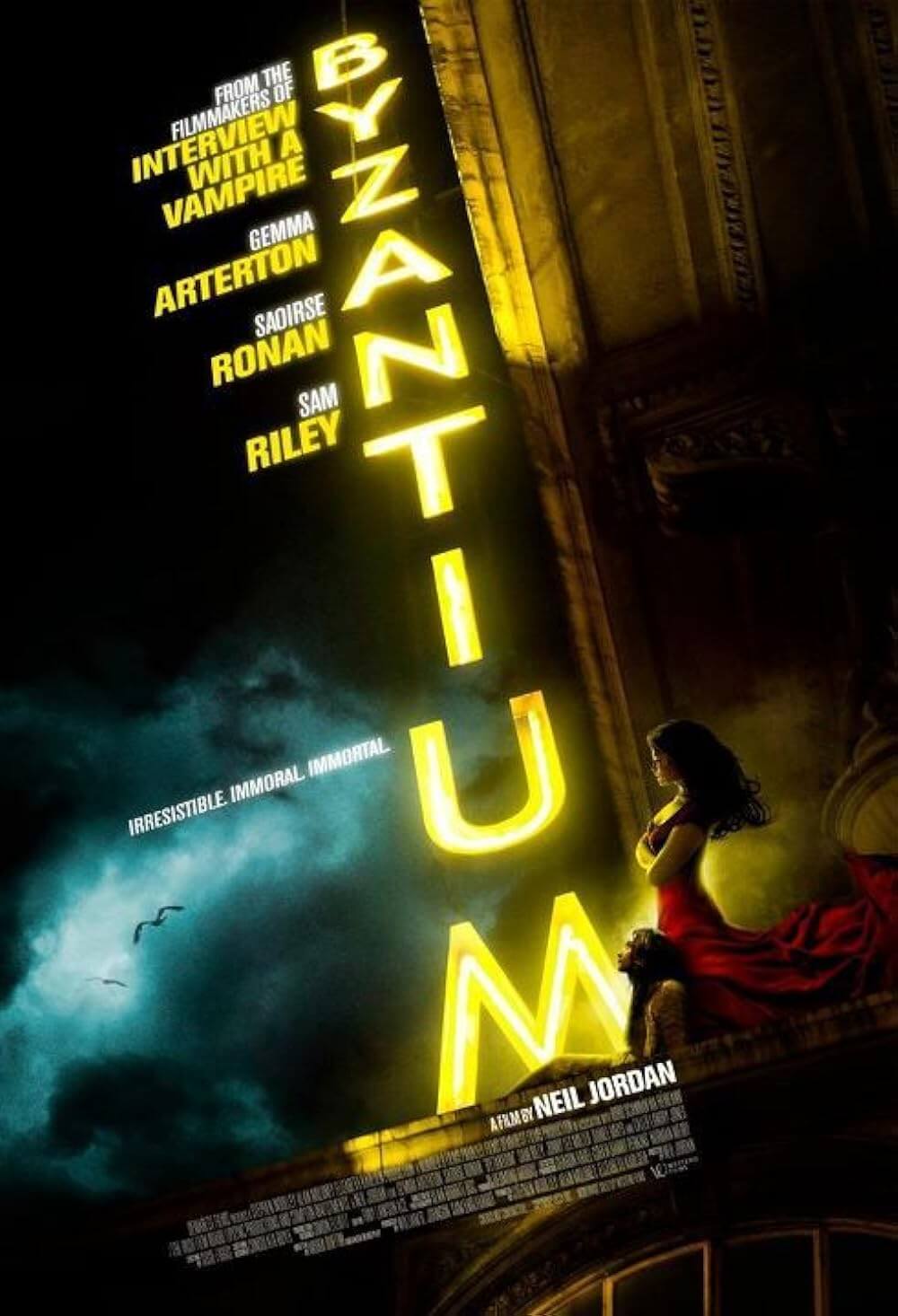

Byzantium

By Brian Eggert |

For 200 years, Clara and Eleanor have survived as mother and daughter by moving from place to place, each locked into the roles they inhabited when they were made into soucriants, a kind of vampire. Ever shielding her offspring, Clara, played by a sexualized Gemma Arterton, was turned after she was forced into a life of prostitution. Now it’s all she knows, save for being a protective mother. Clara’s daughter Eleanor is played by Saoirse Ronan, whose azure eyes give off melancholic and reflective expressions seen as angelic in Eleanor’s exclusively aged victims. Raised in a convent until she was turned at the age of 16, Eleanor takes life only when beckoned by the nearly dead. In Neil Jordan’s Byzantium, Clara and Eleanor’s centuries-old story does not unfold like a history, reliant on a chronological retelling of past events. Rather, the contemporary setting is gradually informed by Eleanor’s desire to share her past with someone other than her future-minded mother. Again and again, as if stuck in a loop, she writes out her chronicle like a fairy tale, but each time she destroys her writing to preserve their secret.

Screenwriter Moira Buffini is a name to remember. Her 2011 adaptation of Jane Eyre may be the best version of Charlotte Brontë’s novel yet put to film. In 2010, she adapted the graphic novel Tamara Drewe for director Stephen Frears, another film that starred Arterton as a complex, at times puzzling character whose beauty stood as a pretense for her inner complication. With Byzantium, Buffini adapted her 2008 play A Vampire Story for the Irish director of The Crying Game into a literate and carnal tale, which contains a few familiar elements of the vampire genre but also several innovations. Everlasting youth, a requisite invite into a victim’s home, and a thirst for blood may be common, but that’s where the familiarity ends. Inducted into a strict misogynist order of male soucriants just waiting for her to make a mistake, Clara stole her life as an immortal, a fangless, wandering existence wherein this reckless predator punctures her victims with an elongated thumb nail to drink heartily. And creating a soucriant isn’t as easy as a bite on the neck and a taste of fleshy iron. It involves a perilous slog out to a mysterious island, a climb up to a darkened hovel, swarms of bats, a reflection of one’s Self, and a mountain where waterfalls of blood signal a transformation.

Jordan’s sophisticated treatment of these characters is appropriately mythic and deliberately paced, with the story unfolding in a novelistic fashion, and the director’s recurrent themes of storybook fairy tales and complicated women enhancing everything onscreen. Never settling, Clara and Eleanor move from their shabby tower block to a small seaside town after one of the male soucriants comes sniffing, hunting Clara down as females aren’t allowed to create, and she leaves him beheaded. They settle down with Noel (Daniel Mays), one of Clara’s lonelier Johns, in his family’s run-down hotel called “Byzantium.” Take the name as a sign that things unfold in a complicated, labyrinthine manner. As Clara sets up a brothel in the hotel to support her child, Eleanor drifts into both her own head and into the life of young Frank (Caleb Landry Jones), a teenage boy with leukemia, whose anti-coagulants cause him to gush blood when pricked. To keep the appearance of normalcy, Eleanor joins Frank’s school and is tasked with an assignment to write about herself. But her eventual, truthful essay about her origins as a soucriant, described as a fusion of “Edgar Allen Poe and Mary Shelly”, is perceived to be a cry for help from a child with troubles at home. Meanwhile, as the faculty at school (Tom Hollander and Maria Doyle Kennedy) assumes the truth is a sign of something more, the picture presents an affecting metaphor for the survival and independence of strong women.

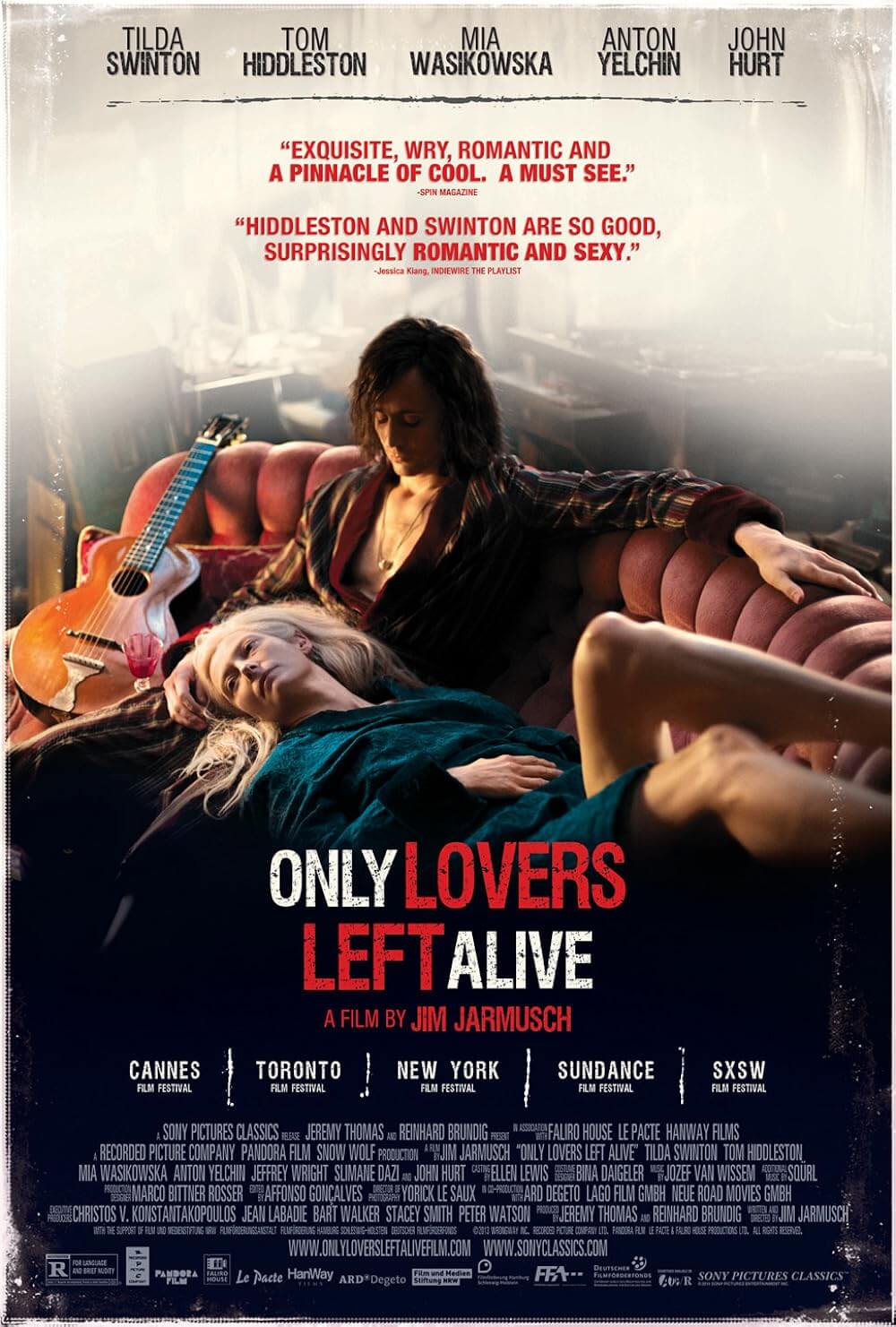

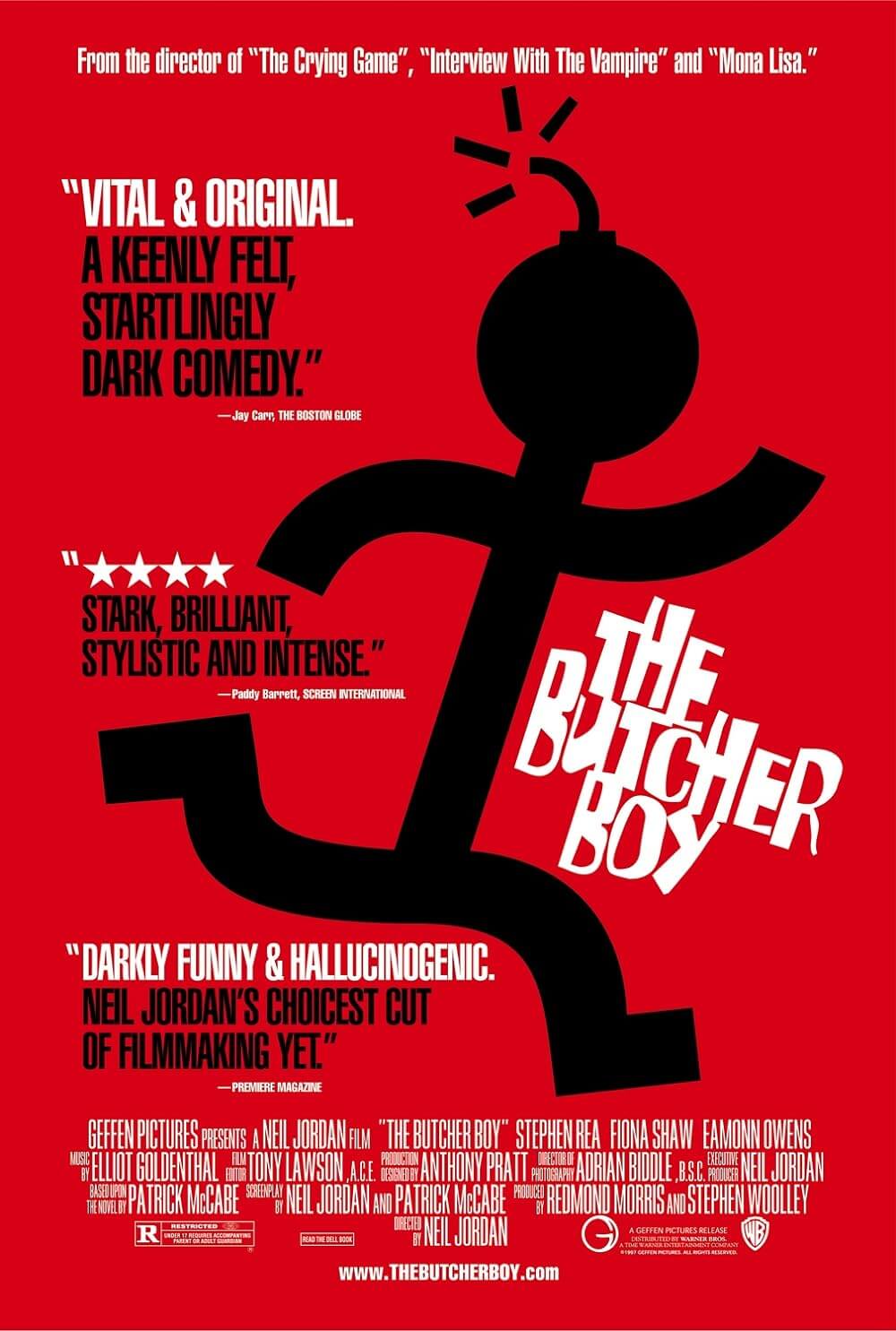

There may be a temptation to draw comparisons between Byzantium and Twilight. Resist it. Jordan’s film is far too smart and pensive to warrant an association with Stephenie Meyer’s juvenile series, with its wishy-washy protagonist and soap opera emotions. A better comparison exists between Jordan’s film and the Swedish Let the Right One In, or even its American remake, Let Me In. But Jordan’s film is beyond those. In the wake of popularized vampires—the Twilight saga, TV’s True Blood and The Vampire Diaries, Tim Burton’s Dark Shadows, Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, and Amy Heckerling’s Vamps—one must question whether or not the overexposed creatures can still have a serious impact on audiences. Jordan’s last foray into vampire territory was his 1994 adaptation of Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire, an admirable effort but obviously a major studio project. This director has always been more comfortable with smaller, more intimate projects away from the mainstream, such as The Butcher Boy or Ondine. Fortunately, Byzantium is such a project; released into art house theaters by IFC, it’s a film that audiences will have to seek out. And your search will result in a discovery that Jordan’s admirers could have predicted: however familiar the material, his picture is nothing like commercial vampire stories so prevalent today; instead, it’s a multi-textual tale of gothic woe and gorgeous imagery.

Director of photography Sean Bobbit (Shame and The Place Beyond the Pines) captures images that remind us why Jordan isn’t associated with commercial filmmaking—his work looks like physical photography, as opposed to digitized images manipulated and cleansed for its eventual release on multi-platform home video. Bobbit’s color palette contrasts muted and weathered earth tones, found off the beaten path across locations in small Irish communities, touched with immaculate storybook reds. In one sequence late in the film, Clara recounts her voyage to the soucriant island, where ecstasy and elation overcome her as cascades of blood wash her free of mortality. Another kind of enthralled beauty is found as Clara and Eleanor trek across the countryside, and they’re dwarfed by huge cabbages in the foreground; they sleep in the field, and a cricket walks across Eleanor’s head in a moment of subtle poignancy. Consolata Boyle’s costumes are lavish, from Clara’s bodices to Eleanor’s red riding hood coat, to the period dress of Ruthven and Darvel (Jonny Lee Miller and Sam Riley)—two men from Clara’s distant past. To put it simply, the look of Jordan’s film is unforgettable. And editor Tony Lawson assembles the film with temperance, using classical logic to inspire his cuts. This is grand filmmaking all around, containing beautiful, horrific images we won’t soon forget.

Jordan’s casting adds to the film’s prevailing sense of dour realism, his choices heightening its undercurrents of mythology. Choosing Ronan to portray a 200-year-old contained within a teenage body couldn’t have been more inspired; she’s capable of housing ageless mystery behind her pale eyes and has carried a storybook quality since Hanna. Landry Jones, best known from X-Men: First Class, has a fragile, offbeat manner that resists his association with teendom. As for Arterton, she’s like a force of Nature here, impassioned by Clara’s desperate need to protect her centuries-old child and using her lusciousness as the means to satisfy her ruthless character’s bloodlust. Jordan must have seen Arterton’s performances in The Disappearance of Alice Creed or the above-mentioned Tamara Drewe, and then tapped into her rarely seen, considerable talent—something few filmmakers have managed to do. The supporting players are equally good: Lee Miller is particularly despicable as Clara’s entry point into prostitution; Riley remains mysterious to the end; and the uncredited Hollander brings much to his minor role.

Jordan’s casting adds to the film’s prevailing sense of dour realism, his choices heightening its undercurrents of mythology. Choosing Ronan to portray a 200-year-old contained within a teenage body couldn’t have been more inspired; she’s capable of housing ageless mystery behind her pale eyes and has carried a storybook quality since Hanna. Landry Jones, best known from X-Men: First Class, has a fragile, offbeat manner that resists his association with teendom. As for Arterton, she’s like a force of Nature here, impassioned by Clara’s desperate need to protect her centuries-old child and using her lusciousness as the means to satisfy her ruthless character’s bloodlust. Jordan must have seen Arterton’s performances in The Disappearance of Alice Creed or the above-mentioned Tamara Drewe, and then tapped into her rarely seen, considerable talent—something few filmmakers have managed to do. The supporting players are equally good: Lee Miller is particularly despicable as Clara’s entry point into prostitution; Riley remains mysterious to the end; and the uncredited Hollander brings much to his minor role.

Surrounded by men both kind and cruel, Clara and Eleanor’s feminist account in Byzantium is a fairy tale lined with gravitas, intelligence, and, in the end, independence—both for the characters and Jordan’s film within the larger continuum of vampire stories. The director’s approach is nothing short of graceful, as he and Buffini mine these characters for everything they’re worth, while Javier Navarette’s sorrowful score deepens the material with heightened solemnity. From the stunning compositions to Eleanor’s thoughtful narration to the poetic drama of Jordan’s treatment, the theme of storytelling itself unfolds and transforms what may be considered familiar vampire material into operatic fantasy. Jordan’s methods are complex, blending images of Clara and Eleanor’s reality with their writings, memories, and dreams to create a mosaic narrative that resists convention at every opportunity (his approach here recalls what Anthony Minghella did on The English Patient). Only through an ever-changing wellspring of storytelling techniques does this tremendously effective film come together and, in the end, overwhelm it with its sensitivity, violence, and elegance.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review