Burning

By Brian Eggert |

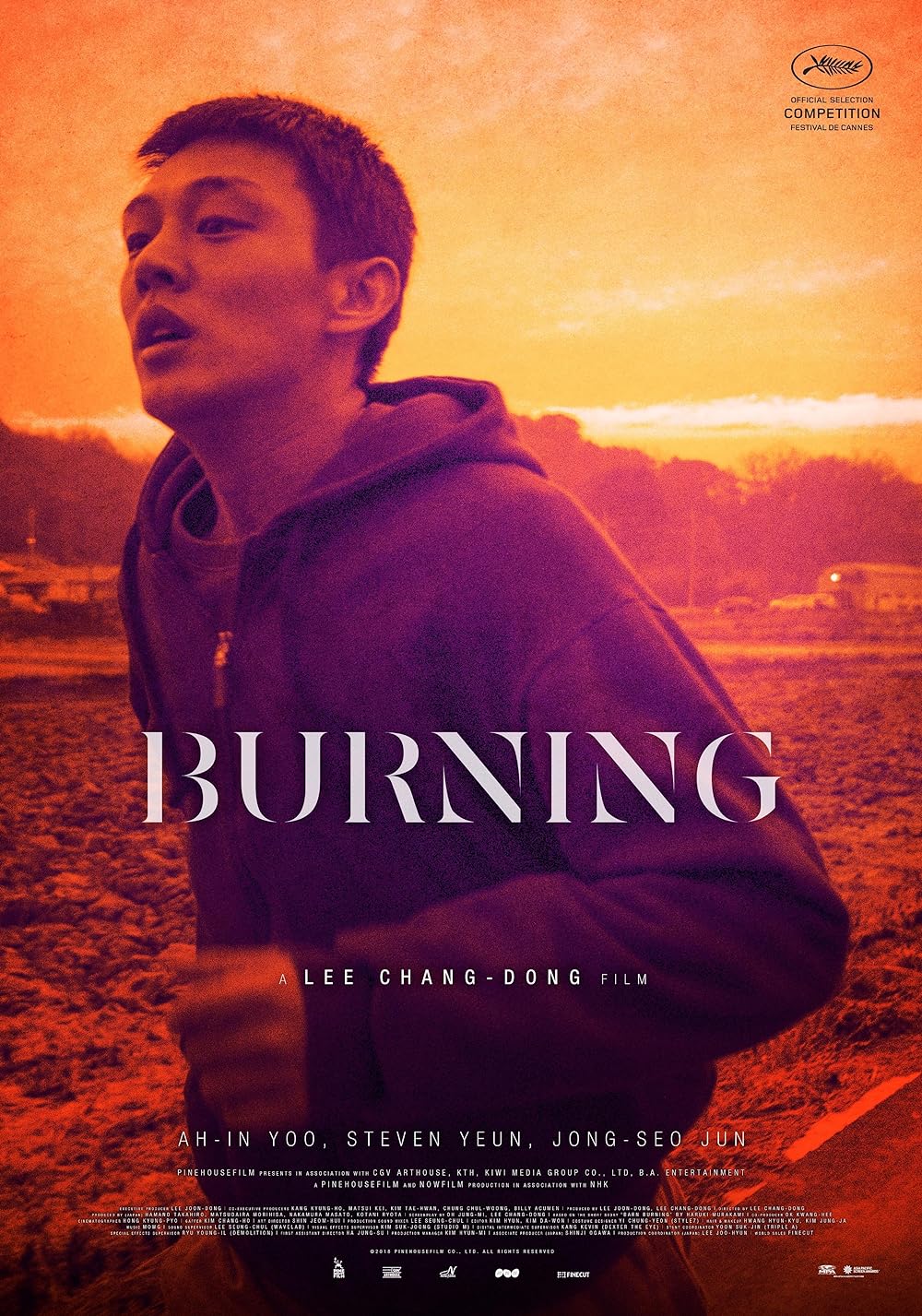

Our perceptions are all we have. Any hope of understanding the world around us on objective terms remains impossible, save for our impressions and assumptions about it. As sociologists have long argued, culture and identity develop from social learning and personal experience. Everything we know is based on what we have been through, what we’ve learned, and how our internal mainframe continues to process that. South Korean director Lee Chang-dong’s Burning revels in the ambiguity between the known and perceived, inhabiting the vast space between the objective and subjective. His thorny character study, its currents of class and masculine identity shaping many of its scenes over the two-and-a-half-hour runtime, portrays its themes in a way that raises more questions than it answers. And despite the viewer’s uncertainty about the motivations behind every character, or whether what unfolds in the film is what actually occurred or just our perception of it, the filmmaking somehow leaves us more engaged than if everything had been delivered gift-wrapped with a tidy bow. Lee’s interest in ambiguity further sculpts his use of the central mystery, how the characters have been written and performed, and where he chose to shoot the film. Best of all, depending on how the viewer interprets it, the film might be a mystery-thriller, it might descend into a social tragedy, or it might be a searing indictment of populist anger.

Burning is only the sixth film by Lee and, in many ways, it’s unlike his earlier human dramas, with their lyrical observations and graceful application of craft. 2010’s Poetry was his last time behind the camera, but before that, his Secret Sunshine (2007) earned him international attention, placing him among the most renown South Korean directors working today. His latest is the very definition of a slow-burner, as the title and aesthetics indicate. Lee and his cinematographer Hong Kyung-pyo (Snowpiercer) affect an obscure mood that grows more puzzling with each scene, capturing moments of subtle performance and a questionable narrative, even as we feel ever-closer to a reveal. Based on Haruki Murakami’s short story “Barn Burning,” at least as a launching pad, Burning‘s title suggests something long since set ablaze, similar to the film’s important feline character, named simply “Boil”—not as in an abscess, but as in to cook or even to aggravate. To be sure, the primary theme of the film seems to be anger, and how anger grows in a person when faced with a dissatisfying or perhaps unknowable perception of the world.

The plot could be distilled into a Hitchcockian scenario on par with Shadow of a Doubt (1943). Having just graduated with a degree in creative writing, Jongsu (Yoo Ah-in) hopes to write novels, but he doesn’t know what to write about. In the meantime, he works as a deliveryman and labors through the tedious chores of his family farm. Not that his family is around. We learn that Jongsu’s father is currently undergoing a criminal trial for endangering his neighbors in a violent outburst. His mother and sister remain estranged. One day, he runs into Haemi (Jun Jong-seo), a promotional model whom he knew as a boy. They start a marginal, indefinite sexual affair that becomes ill-defined when she departs on an African vacation, and then returns with a new friend, Ben (Steven Yeun, incredibly charismatic). Instantly jealous, Jongsu can’t figure out whether Ben has romantic interests in Haemi, and he’s too immature and prideful to ask. Worse, Ben seems to be the personification of everything that Jongsu is not.

The plot could be distilled into a Hitchcockian scenario on par with Shadow of a Doubt (1943). Having just graduated with a degree in creative writing, Jongsu (Yoo Ah-in) hopes to write novels, but he doesn’t know what to write about. In the meantime, he works as a deliveryman and labors through the tedious chores of his family farm. Not that his family is around. We learn that Jongsu’s father is currently undergoing a criminal trial for endangering his neighbors in a violent outburst. His mother and sister remain estranged. One day, he runs into Haemi (Jun Jong-seo), a promotional model whom he knew as a boy. They start a marginal, indefinite sexual affair that becomes ill-defined when she departs on an African vacation, and then returns with a new friend, Ben (Steven Yeun, incredibly charismatic). Instantly jealous, Jongsu can’t figure out whether Ben has romantic interests in Haemi, and he’s too immature and prideful to ask. Worse, Ben seems to be the personification of everything that Jongsu is not.

A character openly compared to “the Great Gatsby,” Ben is situated as the opposite of Jongsu. He’s traditionally good looking, even suave; he has an untold source of wealth; he’s cultured and enjoys cooking fine cuisine; he lives in a posh apartment, and he drives around Paju in a Porsche. By contrast, Jongsu is poor, can’t cook, drives a rusty old truck, and has no sense of the world. “To me, the world is a mystery,” says Jongsu. But unlike the secretly desperate and hollow Gatsby, Ben seems to have everything and everyone figured out. Watch a scene when Haemi and Ben visit Jongsu’s country home, and the three of them smoke pot. Jongsu and Haemi giggle or act out as the drug’s effects take hold, whereas Ben’s reaction is one of tolerance and experience, and the marijuana’s influence doesn’t show. It’s here, about halfway through Burning, that Ben makes a confession: he has a strange hobby, burning down greenhouses. “It’s like they’re all waiting for me to burn them down,” he explains, equating his actions to the “morals of nature.” These lines are delivered cooly, as though it’s the most natural admission in the world. And his next greenhouse, Ben confesses, is very close to Jongsu—”very close.” Jongsu and perhaps the audience suspect that Ben is talking about something else entirely, something far more sinister.

Jongsu, not quite sure what to make of Ben, jogs in his neighborhood in the coming days and weeks, looking for ramshackle greenhouses that might fall prey to Ben’s fire. But none of the greenhouses ever burn down. Indeed, much of Burning takes place between certainties, so that the viewer is never quite sure about whether to take Ben’s confession literally. The in-betweenness of everything in the film is a constant: Jongsu’s family home rests in a small village near the border of North Korea, and the aural presence of the neighboring country’s propaganda machine blares in the distance. A crucial scene occurs at dusk, a period between day and night when Haemi performs what she calls “The Dance of the Great Hunger,” a symbolic performance she learned in Africa about the yearning for something more out of life. Jongsu can relate since much about him exists in a halfway state—he inhabits a family home without a family; he’s ashamed of his past yet confined to its physical spaces; he’s described as a writer but he’s never completed anything. Not having what he perceives to be a fully formed identity becomes frustrated when faced with someone devastatingly confident like Ben.

Lee’s treatment of this basic setup develops into an elusive thriller that may or may not exist entirely in Jongsu’s head. After Haemi goes missing, both Jongsu and the audience begin to wonder if Ben uses old greenhouses as a metaphor for people who have stopped living their life to the fullest. In all of his superiority, charm to spare, and upper-class trappings, is Ben wiping out those he deems to be inferior? Small details begin to accumulate that perpetuate Jongsu’s worst fears, such as the sudden appearance of a cat that may be Haemi’s (though we can’t be sure), or the bored yawns and looks of recognition that Ben gives to Jongsu at a party. Then again, everything about Ben that flames Jongsu’s suspicions could be the vulnerabilities of a deeply insecure male getting the best of him. Lee never confirms the details that propel the plot. They exist because Jongsu perceives them, while confirmation remains just out of reach. Only because Lee situates much of Burning from Jongsu’s perspective does the audience go along with him. And then the director does something in the last 15 minutes that brings everything into question; he shifts the perspective to Ben, implanting a seed of doubt that carries through the horrific climax, and the final moment that continues to haunt the viewer long after the end credits stop rolling.

Lee’s treatment of this basic setup develops into an elusive thriller that may or may not exist entirely in Jongsu’s head. After Haemi goes missing, both Jongsu and the audience begin to wonder if Ben uses old greenhouses as a metaphor for people who have stopped living their life to the fullest. In all of his superiority, charm to spare, and upper-class trappings, is Ben wiping out those he deems to be inferior? Small details begin to accumulate that perpetuate Jongsu’s worst fears, such as the sudden appearance of a cat that may be Haemi’s (though we can’t be sure), or the bored yawns and looks of recognition that Ben gives to Jongsu at a party. Then again, everything about Ben that flames Jongsu’s suspicions could be the vulnerabilities of a deeply insecure male getting the best of him. Lee never confirms the details that propel the plot. They exist because Jongsu perceives them, while confirmation remains just out of reach. Only because Lee situates much of Burning from Jongsu’s perspective does the audience go along with him. And then the director does something in the last 15 minutes that brings everything into question; he shifts the perspective to Ben, implanting a seed of doubt that carries through the horrific climax, and the final moment that continues to haunt the viewer long after the end credits stop rolling.

Similar to Jongsu and his need to make sense of the world before he sits down to a writing project, the viewer who tries to make sense of Burning as a straightforward thriller will find themselves frustrated and unsatisfied. Much as in life, we must supply our own answers through the perceptions available to us. Lee has created an ambiguous film that, if viewed as a genre puzzle, confounds, but if viewed as a study of masculine resentment and inadequacy, it offers a wealth of insight. Far less straightforward than Lee’s previous films, the screenplay by Lee and Oh Jung-mi blends the foggy story with individual moments of beauty that force the viewer to question the purpose of any given scene—which is a way of explaining that Burning ruminates rather than demarcates. Lee’s visual approach, too, aligns with the film’s themes about the illusory haze in which we all exist and try to make sense of, by occupying an almost impressionistic palette and editing style. Burning‘s commentary on angry people who lash out because of their futile attempts at control, or their failure to assert themselves in an uncertain world, feels achingly germane, and Lee isn’t afraid to make a brief but noticed connection between Jongsu and the conspicuous presence of a certain politician. Perfectly calibrated as a piece dependent on nuanced performances and an exacting tone, Burning rewards those willing to invest and engage in all that Lee refuses to spell-out or show to his audience.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review