Bros

By Brian Eggert |

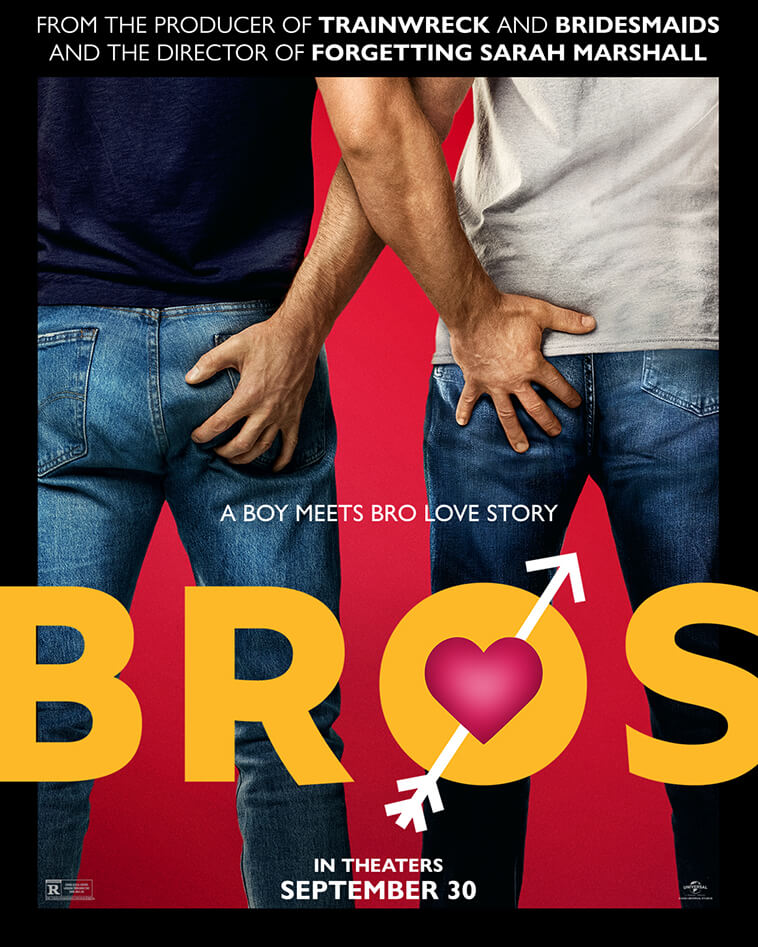

In Bros, Billy Eichner plays Bobby, a gay podcaster and author whose interest in LGBTQ+ history earns him a meeting with a Hollywood executive. The suit tells Bobby that his studio wants to make a movie showing how queer and heterosexual relationships aren’t so different. Bobby, only a touch less angry than Eichner’s hilarious persona on Billy on the Street, responds by explaining that gay relationships are different and shouldn’t be contained within traditional storytelling archetypes. So Bobby walks out of the office, determined not to tell stories about unsung and marginalized people within a conventional framework. It’s ironic, then, that Eichner and co-writer Nicholas Stoller, who directed Bros, have delivered such a mainstream rom-com in the tradition of Nora Ephron—ironic, but not hypocritical or without self-awareness. Of course, in real life, that meeting must have gone another way, with a series of notes and compromises customary for a production backed by a major studio, Universal Pictures. The film adheres to a commonplace narrative structure but involves characters who, at best, are usually relegated to the role of the “gay best friend” in Hollywood rom-coms, resulting in a universal story about otherwise sidelined characters.

Bros has been touted as the first studio film to feature all LGBTQ+ actors in the principal cast, but it’s also one of only a handful of queer movies produced by a larger studio. As Bobby often notes, heterosexual actors usually play gay characters in mainstream cinema, often in tragic roles (think Tom Hanks in 1993’s Philadelphia or Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhaal in 2005’s Brokeback Mountain). While providing a historical exception, Bros actively comments on these trends, just as it points out the rom-com blueprint while conforming to the model. The film also weaves in themes about the suppression of queer history, including a subplot about Bobby as the director of a new LGBTQ+ history museum and his persistent need to remind people that the queer community continues to struggle to have its stories told. In a lesser film, these knowing flourishes might not have worked. But Eichner and Stoller’s screenplay effortlessly makes them part of Bobby’s identity and the plot, calling itself out as a representational landmark while normalizing its story in a familiar structure.

The writers perform a delicate balancing act that never resorts to a parody of rom-coms even as it comments on and embraces the tropes therein. It adopts a rare self-consciousness that goes beyond homage to make reference points part of the text. Earlier examples of this approach include Wes Craven commenting on the slasher movie within Scream (1996) or Edgar Wright’s various takes on zombie, buddy cop, or pod-people fare—all of which acknowledge the genre’s familiar beats even while blissfully replicating the tempo. A more cynical and outrightly parodic film might have ended up like They Came Together (2014), director David Wain’s lampooning of Ephronisms. But somehow, Bros manages to make direct references to When Harry Met Sally (1989) and You’ve Got Mail (1998) yet also obey their template without feeling banal. The viewer recognizes that the characters aren’t usually the sort who appear in rom-coms; at the same time, the familiar trappings—from a seasonal montage in New York to the climactic and public declaration of love—couldn’t be more Ephrony.

Bros also has the distinction of introducing Eichner as an actor with impressive dramatic range. As Bobby, he has plenty of loud and in-your-face moments that his Billy on the Street fans will recognize. But Bobby’s outrageous behavior might just mask his inner discontentment. In the opening scenes, he justifies his life of random hookups with his professional success, rationalizing that he has “a lot more than a lot of people have.” But his resting angry face and pride in being “emotionally unavailable” might be a shield, and his inability to flirt has made him an outsider in the gay dating scene. Then he meets Aaron (Luke Macfarlane), a jockish hunk who, like Bobby, doesn’t date and avoids commitments. However, Aaron’s tendency to disappear like Batman attracts Bobby, and despite some initial bumps and hesitations, they start a romantic relationship. Yet both have insecurities they must overcome: Bobby worries about his skinny appearance next to the ripped physiques of the men Aaron is accustomed to; Aaron feels intimidated by Bobby’s confidence and struggles with some internalized homophobia. But Bobby’s powerful speech that “confidence is just a choice you make” bonds them further and becomes the film’s emotional breakthrough.

Bros also has the distinction of introducing Eichner as an actor with impressive dramatic range. As Bobby, he has plenty of loud and in-your-face moments that his Billy on the Street fans will recognize. But Bobby’s outrageous behavior might just mask his inner discontentment. In the opening scenes, he justifies his life of random hookups with his professional success, rationalizing that he has “a lot more than a lot of people have.” But his resting angry face and pride in being “emotionally unavailable” might be a shield, and his inability to flirt has made him an outsider in the gay dating scene. Then he meets Aaron (Luke Macfarlane), a jockish hunk who, like Bobby, doesn’t date and avoids commitments. However, Aaron’s tendency to disappear like Batman attracts Bobby, and despite some initial bumps and hesitations, they start a romantic relationship. Yet both have insecurities they must overcome: Bobby worries about his skinny appearance next to the ripped physiques of the men Aaron is accustomed to; Aaron feels intimidated by Bobby’s confidence and struggles with some internalized homophobia. But Bobby’s powerful speech that “confidence is just a choice you make” bonds them further and becomes the film’s emotional breakthrough.

Produced by Judd Apatow, Bros has Apatow’s casual, occasionally improvisational quality that recalls Stoller’s other film in the Apatow-verse, Forgetting Sarah Marshall (2008). There are plenty of pop-culture references, such as Bobby’s critique of Schitt’s Creek for popularizing LGBTQ+ issues when he cherished their niche quality (as someone who preferred superheroes when they were a minor subculture rather than the mainstream, I can relate to his contrarianism). A running joke about the desperate attempts of the “Hallheart Channel” to appeal to queer audiences also proves funny. Perhaps the best gag involves Debra Messing complaining that every gay man assumes she’s her character from Will & Grace. Elsewhere, there’s an openness to gay sexuality concerning Grindr and other LGBTQ+ dating apps; it’s also open to how group sex dynamics might extend beyond the bedroom. But the film’s depiction of gay sexuality remains rather tame in terms of nudity and representation, considering some of Apatow’s other credits. It seems that when penises appear onscreen as a joke, they’re safe for general audiences; when they’re attached to gay men in sexual situations, they’re edited from the R-rated movie entirely. Some things never change.

The screen story follows Bobby and Aaron’s relationship on a familiar trajectory, from their blissful courtship to a sudden fallout that signals the third act to the last-minute declaration of love (featuring Eichner’s impressive singing voice). Along the way, Bros features comical scenes where Bobby must contend with his museum’s board of wacky and diverse characters—recalling Meg Ryan’s bookstore employees in You’ve Got Mail—each vying for their group to receive an exhibit (bisexual, trans, lesbian, et al.). And the scenes in which Bobby grills Aaron’s mom (Amanda Bearse) about why she doesn’t teach queer topics in her second-grade class create a familiar tension for the central couple. Still, the film is smart about how it adopts the usual rom-com format while also talking about LGBTQ+ concerns in a way that will force someone not directly involved in that community to, hopefully, receive it with openness. Then again, for all the film’s inclusions about LGBTQ+ history, it’s not above pairing them with a Night at the Museum (2006) reference.

Fortunately, Bros never feels overly preachy about representation, though it could have easily devolved into a history lesson or lecture. Instead, it’s a confirmation that the LGBTQ+ community deserves representation, and that the film is aware of its significance in queer film history. Years from now, maybe Bros will seem like nothing more than an obvious starting point to an influx of mainstream movies focused on LGBTQ+ characters and made by LGBTQ+ filmworkers. That’s the dream. But, for now, Eichner and Stoller contain their message within an accessible, often hilarious, and tender film that will satisfy any fan of traditional rom-coms, giving us, as the poster’s tagline suggests, “all the feels.” Although the film might become repetitive in its commentary about Bobby’s story being different but the same—that not all love works out like the movies or heteronormative models suggest, except when it does—it’s such a pleasure to be in Bobby and Aaron’s company that it hardly matters. More subtle is how, beneath its commentary and familiar scenario, there’s also a welcome message about accepting and allowing others to love and desire how they see fit, regardless of how it’s labeled. In the words of Harvey Fierstein, who appears in a brief cameo, have fun and be your true self now, because you’ll be dead soon.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review