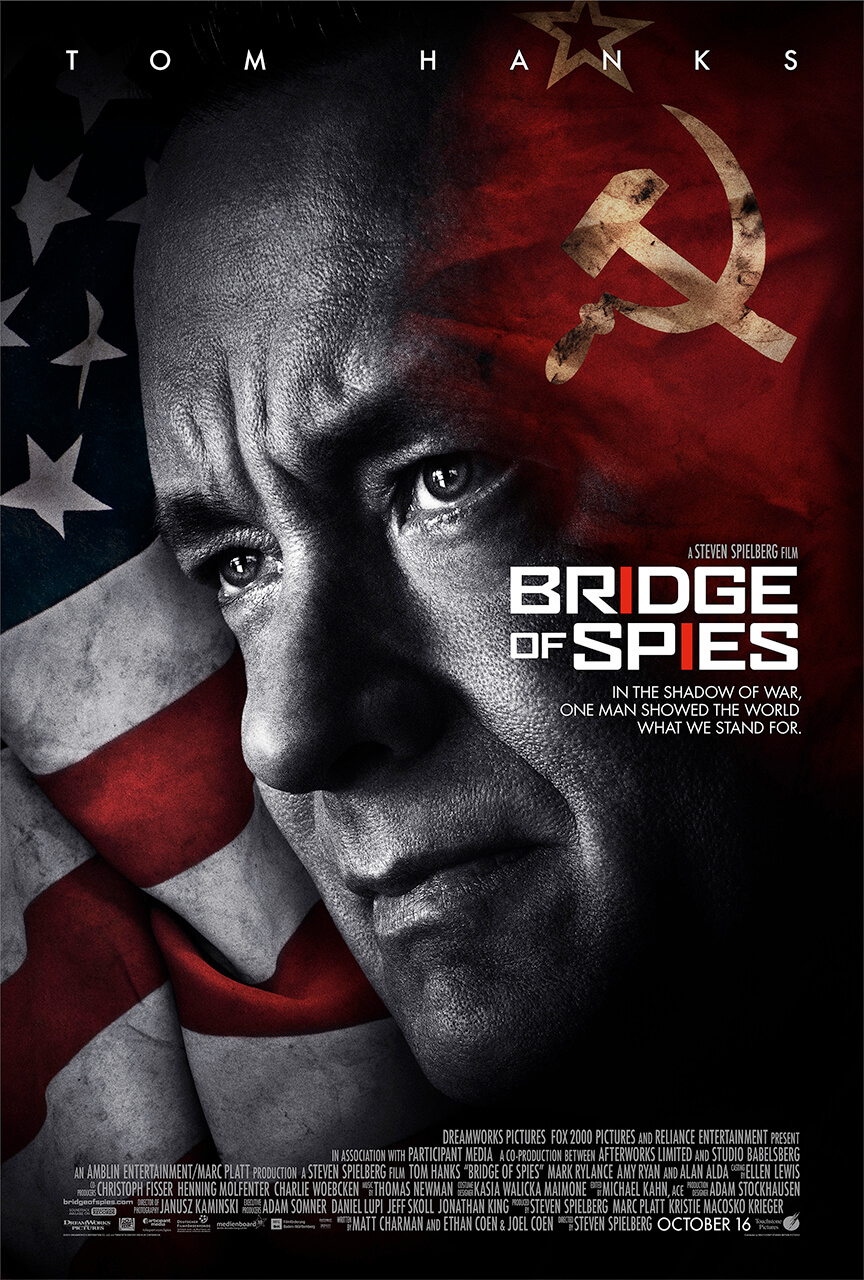

Bridge of Spies

By Brian Eggert |

Steven Spielberg’s old-fashioned treatment of a true-life Cold War drama has surprising contemporary relevance in Bridge of Spies, a smart historical picture about espionage, political paranoia, and the importance of humanism. The story pits an everyman attorney, lovingly played by Tom Hanks, against the courts for its unconstitutional treatment of spies, as well as the persistent suspicions of America and her enemies, leading to a white-knuckle prisoner exchange. Compared to the black-and-white villains of Spielberg’s World War II films (Saving Private Ryan, Schindler’s List, etc.), the conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union over information and nuclear power feels submerged in the fog of war. Likewise, today’s strained relations with various countries (including Russia) seem far more complicated than these comparably straightforward Cold War proceedings. Spielberg’s smooth, Capra-esque handling of this otherwise multifaceted conflict streamlines the material for modern audiences, delivering an accessible, incredibly well made, and wholly enjoyable picture about the importance of recognizing the humanity of our enemies.

The basic story begins in 1957, following a Soviet spy based in New York. Rudolf Abel (Mark Rylance, fantastic) spends his days painting in slow, methodical strokes, demonstrating the kind of patience it requires to subsist in deep cover for years. Once caught, he spends years in prison until 1962, when he’s to be tried for espionage. There’s no doubt Abel is guilty of his accused crimes, but to demonstrate for the world at large that U.S. courts will provide Able a fair trial, they assign a respectable insurance attorney. James B. Donovan (Hanks), an all-around decent man, married to a supportive wife (Amy Ryan) and father of two kids, receives the thankless assignment from his partner (Alan Alda), which is described as Donovan’s honor to lose (“Everyone will hate me, but at least I’ll lose,” he quips). However, upon meeting Abel, Donovan finds him to be an honorable, if stoic man who did as his country instructed: spied. Just because he’s the enemy doesn’t mean he shouldn’t be afforded every protection under the U.S. Constitution—an argument he takes to the Supreme Court. Moreover, there’s considerable evidence to prove the investigation didn’t have the proper warrants. Nevertheless, the judge (Dakin Matthews) deems Abel guilty before the trial even begins, and Abel’s life is spared only because Donovan suggests he might be of better use alive.

Meanwhile, Bridge of Spies crosscuts to the development of the first U-2 spy plane mission flown by American pilot Francis Gary Powers (Austin Stowell), who’s inevitably shot down and captured by the Soviets. And then there’s Frederic Pryor (Will Powers), an American graduate student who made the mistake of studying Soviet economics in Berlin. He’s captured by the East Germans. Just as Donovan predicts, the U.S. government now needs Abel for a prisoner exchange, and the CIA wants Donovan to negotiate it. By this time, the film has built up enough good will toward and confidence in Donovan that his trip to Berlin—in the interest of absolute secrecy, he tells his wife he’s on a fishing trip to England—becomes an almost humorous, if dangerous, affair. To be sure, his clever cajoling and verbal jousting with both Soviet and one sharp East German attorney (Sebastian Koch) turns coded dialogue into frank, often funny exchanges in which Hanks’ natural charm shines (he jokes that the newly named countries, the German Democratic Republic and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, are far too long). He’s stuck in a wintry, gray place and stricken with a lingering cold, and so he rushes to return home to bed; yet, he’s able to do what his CIA handlers and other various politicians could not by talking his way into a victory. Watching it all unfold is a fascinating pleasure.

Always a technical wizard, Spielberg’s stylistic flourishes are less pronounced but no less carefully composed. Foremost is cinematographer Janusz Kaminski, who shoots on 35mm to create the classical look sought by Spielberg. Kaminski also color-times the celluloid in muted colors to evoke the gray-toned Cold War atmosphere in expressionistic touches, and intentionally overexposes certain scenes where blinding light burns through windows (recalling several shots Kaminski composed for Spielberg’s Minority Report). Spielberg’s longtime collaborator frames iconic shots that are both original and evocative of classic cinema. One such shot takes place just after the exchange, looking down from an angle on Donovan, alone on the bridge. Another finds Donovan under an umbrella in the rain as he ducks beside a car, hiding from a tail. Elsewhere, production designer Adam Stockhause and costumer Kasia Walicka-Maimone render the Cold War era sets and wardrobes with impeccable attention. If there’s an underwhelming quality to Bridge of Spies, it must be Thomas Newman’s music (Spielberg’s usual scorer, John Williams was unavailable due to a “minor health issue”), which is bland and shrug-worthy.

Politically, there’s certainly an air of American Exceptionalism at the film’s center, whereby Donovan argues that the U.S. must hold itself at a higher regard than its enemies, and resist playing by their games. One heavy-handed visual juxtaposition sets German refugees gunned down as they try to cross the Berlin Wall against New York children hopping backyard fences, suggesting the vast differences between Cold War East Germany and America. Another exceptionalist juxtaposition occurs when we see Powers brutally interrogated onscreen (in a sequence recalling Costa-Gavras’ The Confession from 1970), whereas the film carefully avoids showing Abel’s interrogation at the hands of the CIA, which presumably wasn’t a pleasant experience for Abel. In turn, we’re able to demonize the Soviets and conveniently ignore the reality of U.S. interrogation tactics. Nevertheless, the overarching theme in Bridge of Spies regards even the worst enemies as human beings worthy of the treatment that our Constitution affords. When we ignore those laws to exact a virtual drumhead trial and achieve a quick, popular resolution, we lose a piece of who we are. (Although the film never makes the association itself, one cannot help but think about a modern-day parallel, where the U.S. government captures a terrorist and refuses them a fair trial.) Sun Tzu wrote, “If you only know yourself, but not your opponent, you may win or may lose. If you know neither yourself nor your enemy, you will always endanger yourself.” Christ took it even further and said, “Love your enemies.” The point is, your enemies deserve your respect.

Originally called “St. James Place” and written by Matt Charman, the screenplay received a rewrite from auteurs Joel and Ethan Coen, taking a writers-for-hire gig (much as they did for last year’s WWII pic, Unbroken). But the Coens’ signature wordsmithing is evident in the finished film, especially in Donovan’s one-on-one conversations where, using no end of dry humor and wit (the Coens’ dialogue is great in Donovan’s introductory scene, where he defends his insurance company client against five separate claims), he shrewdly convinces stern men to do something they do not want to do. After all, the original deal was an exchange of Abel for Powers, but as history shows, Donovan negotiates one Soviet for two Americans. The Coens’ smart dialogue in Bridge of Spies is enhanced by the enduring charm of Tom Hanks. With his Jimmy Stewart quality, Hanks plays a role that suits his innate charisma. Donovan is modest and principled to the core, and Hanks encompasses him completely, delivering another wonderful late-career performance on par with Captain Phillips. From start to finish, Bridge of Spies is an engrossing, expertly made picture from Spielberg, and its historical merits, paired with its contemporary political relevancies, make it a supremely important American film for today.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review