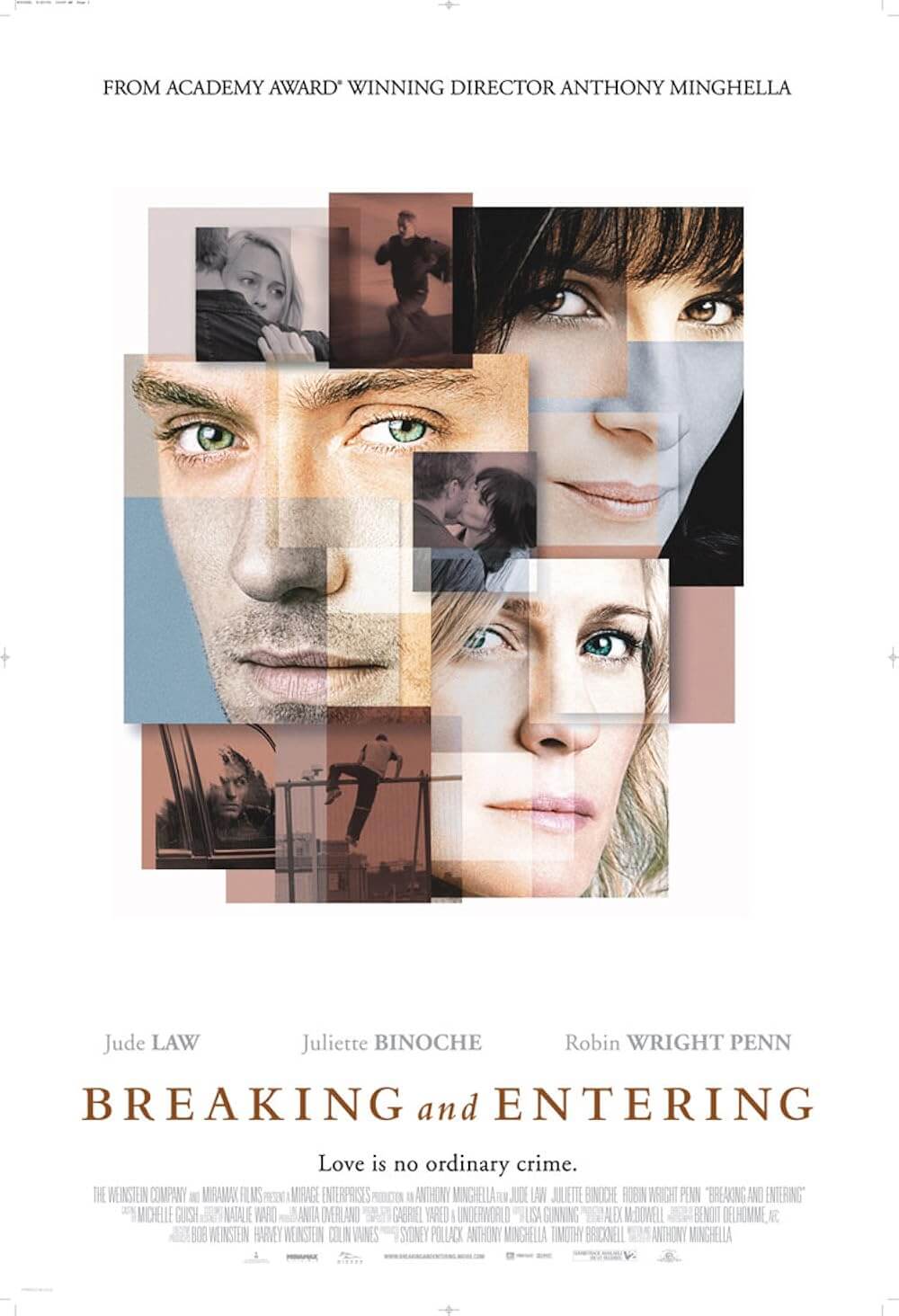

Breaking and Entering

By Brian Eggert |

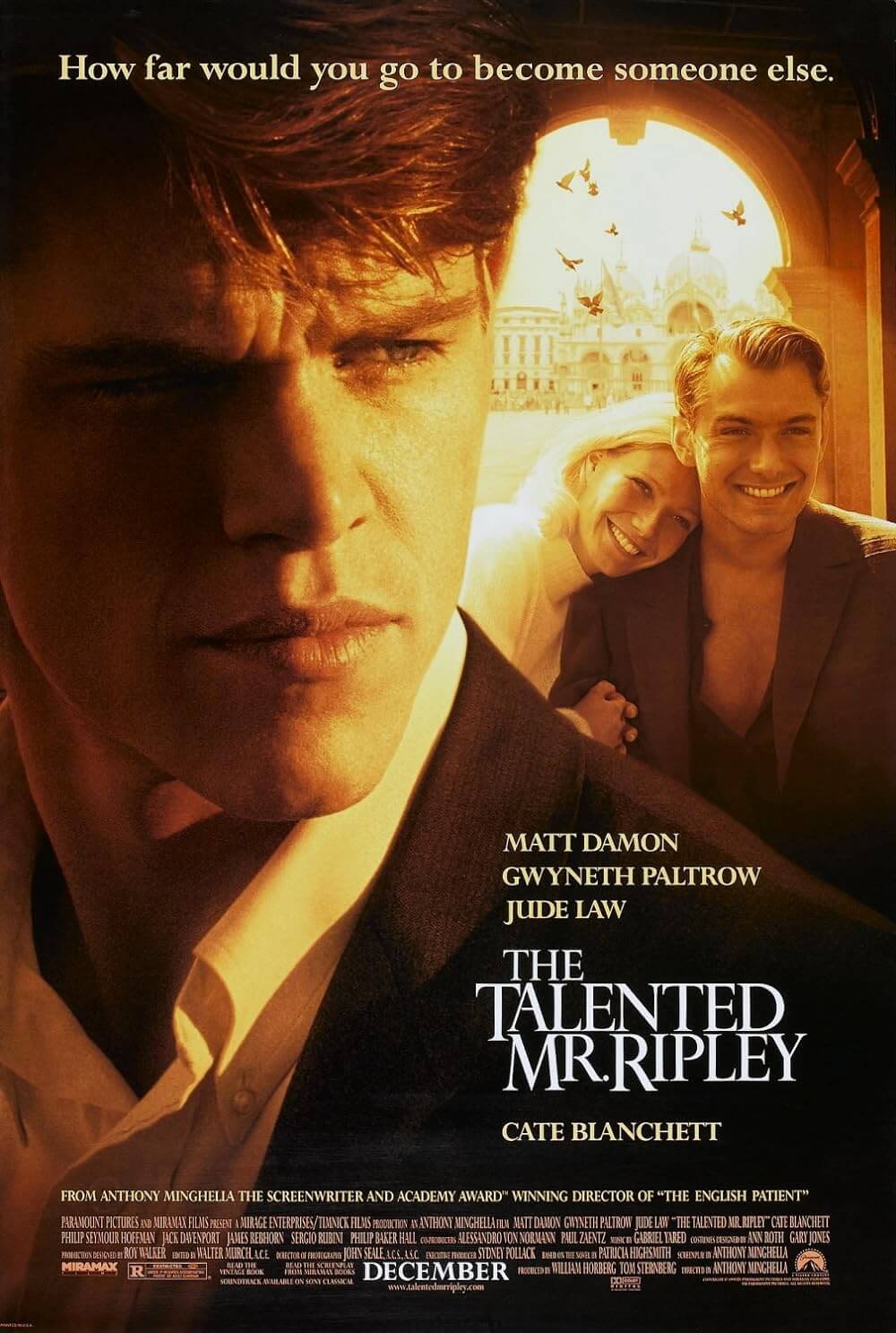

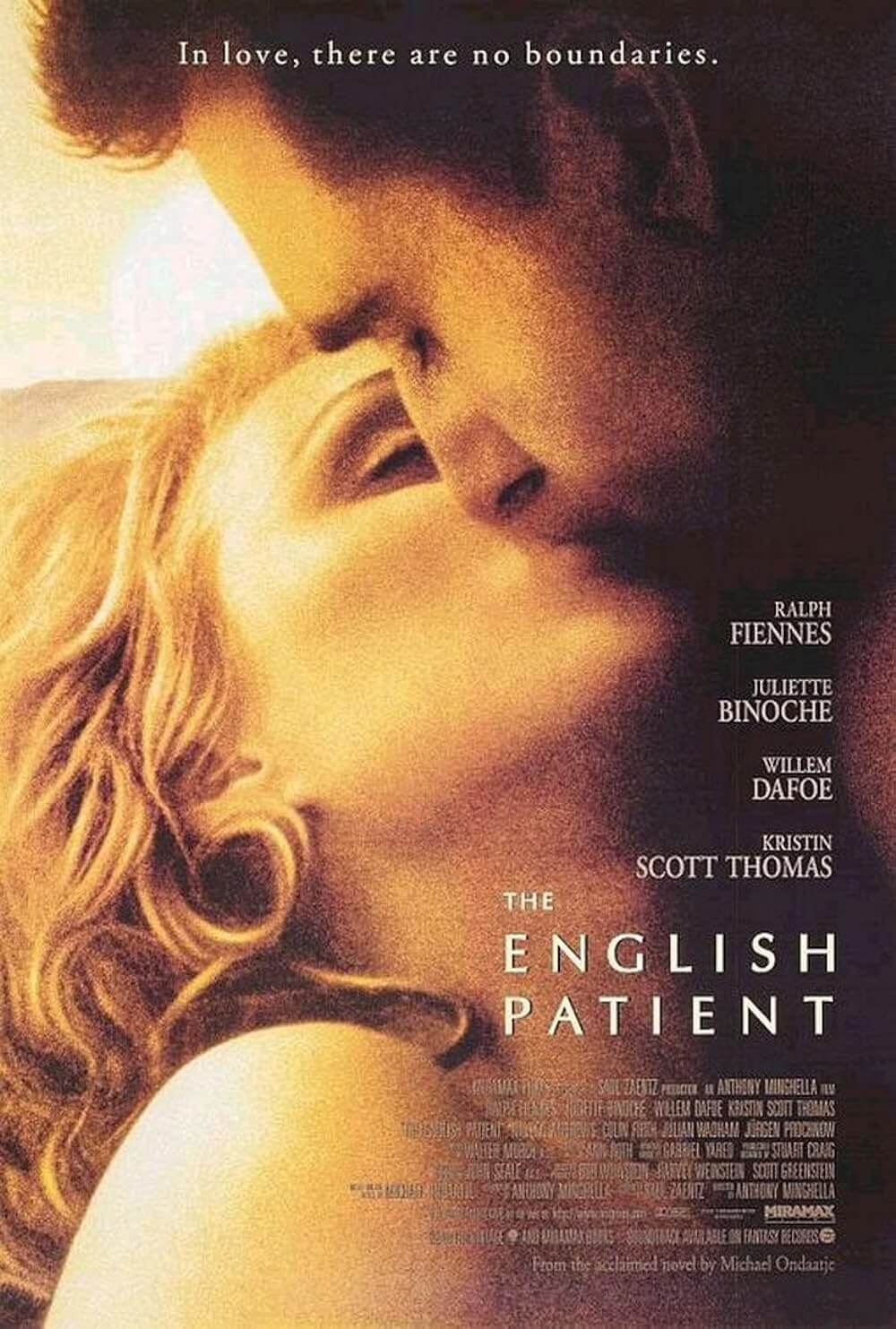

Anthony Minghella’s latest drama demands an attentive audience, one willing to think about metaphors during and after the film. Nearly every name, place, and event in the story can be interpreted as a signifier of a more significant theme related to the film’s plot or title. Minghella’s last three films (Cold Mountain, The Talented Mr. Ripley, and The English Patient) all harbored extravagant emotionalism enhanced by striking locales; with Breaking and Entering, the film’s big ideas meshed with the grim urban locales.

In the sprawl of London, Will (Jude Law), an architect, hopes to rebuild a broken and unfriendly slum to create a unified cityscape. His girlfriend of ten years, Liv (Robin Wright Penn), and her troubled twelve-year-old daughter, Bea, are becoming more and more distant. These problems mirror one another, but Will doesn’t see that at first. He only feels pushed away, and since Liv is not as reconstructible as a building, Will becomes distant. Trapped by Liv’s unwillingness to marry and Bea’s increasing mental illness, Will’s clean, upper-middle-class home becomes less comfortable than the sprawl where he works.

His business is repeatedly robbed by someone who gets in through the roof. One night he sees that a teenage boy is the culprit. Will follows the young thief and discovers where the boy lives. He doesn’t call the police, but instead, he comes back the next day to find the boy’s single mother, a Bosnian seamstress named Amira (Juliette Binoche). At first, he pretends he’s a customer and gets his coat fixed; later, he keeps finding reasons to come back. He and Amira become friends; eventually, he falls for her, and they have an affair. From Amira’s point of view, Will is a nice man, and even when she finds out from her son why Will had reason to knock on her door, she continues with the affair. Is Will blackmailing her? Will he turn her son, who has had problems with the law before, into the authorities? She’s conflicted between her genuine feelings for Will and her motherly instinct to protect her son.

Reminding me of Lawrence Kasdan’s Grand Canyon, the characters gracefully interweave in a delicate, heavily readable drama. None of the subplots appear to connect, yet in the end, they dance together in a ballet of symbolism. The metaphors are everywhere, though some are more obvious than others. A fox, somehow finding itself in the city, barks outside Will and Liv’s window—the sound is something like the high-pitched shriek of a man being stabbed—and it drives Will crazy, while Liv doesn’t seem to mind. It’s pointed out to Will that though he seeks something more adventurous, he can’t stand the one thing in his life that’s wild. The most transparent metaphor is a prostitute played by Vera Farmiga (The Departed); she remains at once whorish yet somehow sizes Will up without a second glance. In the end, she ends up being a hooker with a heart of gold (an absurd cliché) and helps Will understand why he’s running from Liv and Bea.

The dialogue in the film addresses the use of metaphors as a problem, but conversely, it uses them in every scene. Will explains that they distance a person from the truth—they make the truth more manageable and ultimately distract from whatever the signified may be. But in the end, I don’t think Will believes that. How can he? Metaphors have helped him to define his entire life. He speaks in metaphors, and he tries to teach the importance of symbols to Bea, who just doesn’t understand. Metaphors are sometimes necessary for those who can not or do not want to see the truth. They add a lyrical appeal to reality, making every truth a song. In Will’s case, metaphors both confuse and clarify his situation.

Minghella infuses his characters and dialogue with weighty representations and codes; for the audience, discovering all those layered meanings is a delight. The characters Will, Liv, and Bea all have names that, if spelled as they sound phonetically, reflect the story’s theme: a group of people concerned about what happens next. The director has a great sensitivity for depth, intelligent writing, and structure. From a certain point of view, the metaphors might be considered hokey, but the talent it takes to create a two-hour mosaic of symbols demands respect and admiration. Though not on par with his The Talented Mr. Ripley or The English Patient, Minghella’s latest shows a different side to the filmmaker—a side that is capable of greatness without the benefit of scenery to drive his story. On a comparably small visual scale, Minghella shows us vast emotional trials and painful realizations; his actors are perfectly cast, and his writing is sharply constructed. While this film may not impact the viewer on the same levels Minghella’s other work might have, audiences will walk away affected by a poem put to film and feel contented by the truths in the director’s symbolism.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review