Bram Stoker’s Dracula

By Brian Eggert |

Bram Stoker’s Dracula opened in 1992 and marked the first significant box-office victory for director Francis Ford Coppola outside of his Godfather trilogy, although the film was not as warmly regarded as attended. Developed and marketed as a faithful adaptation of Stoker’s 1897 novel, the outcome features several scenes straight from the book and not typically included in earlier film adaptations. Yet Stoker’s vision was unquestionably adapted to meet not only Coppola’s and writer James V. Hart’s preoccupations, but also the 1990s culture to which the film was being sold. Their approach turned many moviegoers away by failing to provoke genuine scares and instead strumming the classic tale for its romanticized, sensual themes, rather than the pure horror approach of so many earlier adaptations. But, ornamented with incredible visual and technical bravado, Coppola’s film is a dramatic, literate visual feast of operatic excess to be savored for its finer qualities.

Hart’s script was first brought to Coppola by star Winona Ryder, who sought to make amends with the director after dropping out of The Godfather, Part III on short notice. Much like his third Godfather effort, Coppola saw the project as a moneymaking device to prevent his production company, American Zoetrope, from going bankrupt. Similar motivations drove Coppola to helm Jack (1996) and The Rainmaker (1997), yet unlike those efforts, Coppola allows his imagination out to play here. Grandiose in both its emotional expression and Victorian Gothic stylization, Coppola’s film does not belong to the modern horror genre. It contains no Boo! or Gotcha! moments (for instance, those found in other vampire dramas, Interview with a Vampire and Let the Right One In). Of course, elements of horror such as Dracula’s monstrous manifestations (a wolf-man and a bat-creature) and gallons of blood fill the screen, but these are employed in a metaphoric sense rather than to evoke terror in the viewer. Coppola and Hart present the titular character as a sympathetic villain, not unlike Michael Corleone in Coppola’s Godfather films. Instead of horror, Coppola delivers a love story (complete with the marketing tagline: “Love never dies”) told through vibrant imagery, featuring one of the first cinematic Draculas who is more than a ghoulish bloodsucker.

Though many critics admired the energy and visual inspiration Coppola instilled into his adaptation—most notably Oscar-winning costumes by Ishioka Eiko and gorgeous production design by Thomas Sanders and Garret Lewis—few considered it a faithful translation of Stoker’s book. Coppola’s tone was believed to be too romantic, his Dracula too human, and his narrative more about style than substance. Desson Howe of the Washington Post called the film “an intricately designed bag of wind,” and the critic for Empire Magazine asked, “Has a film ever promised so much yet delivered so little?” Even though most critics gave positive reviews, their critiques censured Coppola for not adhering to the novel. Roger Ebert wrote, “The one thing the movie lacks is headlong narrative energy and coherence.” Moreover, Coppola’s inspirations came more from other films about Dracula than from Stoker’s novel. Details such as Dracula’s line “I never drink… wine” originated with Tod Browning’s Dracula in 1931. More than any one particular element within the film, detractors took greater issue with the pre-title “Bram Stoker’s,” given Coppola and Hart’s considerable liberties with the material. A handful of critics proposed the film should’ve been named Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula. And perhaps they are correct. However, Columbia Pictures undoubtedly chose the title because Universal Studios still owned the rights to the title “Dracula.”

Amid the usual Hollywood deviations in book-to-film adaptations, Hart’s added prologue is set in 15th-century Transylvania and identifies Prince Vlad Dracul (Gary Oldman) as a man so heartbroken that he renounces God and vows to avenge his fallen princess by triumphing over death to become a vampire. Hart also implies a parallel between Dracula’s princess Elizabetha and 1897’s Mina Murray (both played by Winona Ryder), suggesting Dracula’s deathly quest is more about recovering his former love than creating an army of vampires in London (his scheme in Stoker’s text). The film’s Dracula seems almost content in his Transylvania castle until drawn to find his long-lost princess’ London-bound double, Mina. Any mention of spreading vampires throughout the modern world is secondary, except in scenes with Tom Waits’ exceptional rendition of the madman Renfield.

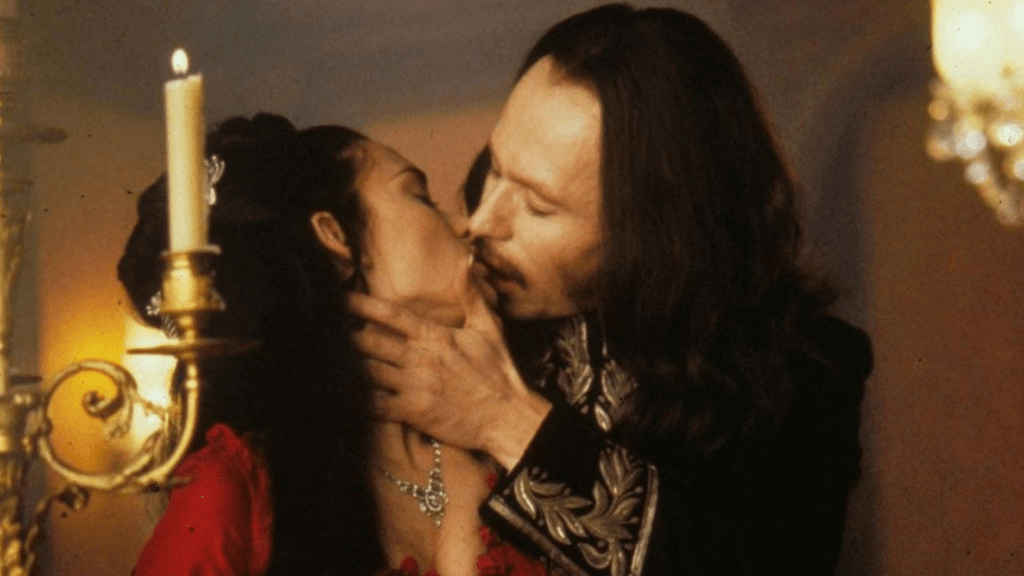

Truly cursed, Coppola’s Dracula seeks redemption rather than satisfying his bloodlust, as in his cinematic predecessors, and becomes a three-dimensional character rather than a monstrous “other” feared and despised by the audience. In a way, we understand him and empathize with him. As the plot unfolds, solicitor Jonathan Harker (Keanu Reeves) travels to Transylvania to finalize paperwork on Count Dracula’s real estate purchases in London and finds himself held captive, where he’s raped and drained of life by Dracula’s vampiric brides. Meanwhile, Dracula sails to England to meet Mina, and, now appearing young and handsome, he assures that the two become lovers. There, he infects Mina’s wealthy friend Lucy Westenra (Sadie Frost), and then finds himself hunted by Prof. Abraham Van Helsing (Anthony Hopkins), as well as Lucy’s trio of suitors: the cowboy Quincey Morris (Billy Campbell), the morphine-addicted Dr. Seward (Richard E. Grant), and her dignified fiancé Arthur Holmwood (Cary Elwes). By the conclusion, Harker joins in their pursuit of Dracula as they confront him in a race to the Count’s castle, where the infected Mina must put her lover to rest.

As in Stoker’s book, sexuality defines the film’s characters in understated ways. Take the flirtatious Lucy, whose sexual preoccupation determines that she must become Dracula’s victim, as female sexual advances are deemed “unnatural” according to Stoker’s text, and thus they must be punished; whereas, uncorrupted, Mina is his subject of love. Yet, scenes between Dracula and Harker in the castle have a certain intimacy. Their scene together where Dracula shaves Harker, their reflection in the mirror showing only the latter, suggests they are the same; Dracula’s reaction to Harker’s blood is orgasmic, whereas his reaction to Lucy or Mina’s blood are lesser so. This leads to a faint allusion that Dracula has been “doomed” to homosexuality, as well as an AIDS-related blood disease, by renouncing God. Certainly, Stoker’s book hinted at Harker’s denial of, but undeniable pleasure in, his conflicting heterosexual urges with the vamp brides. Even Reeves’ wooden performance (the film’s most apparent and most oft-mentioned downfall), his utter lack of sexual chemistry with the willing Ryder, suggests his sexual ambivalence toward females. Audiences of the early 1990s considered Van Helsing’s discussions of blood transfusions and “infection” relative to their AIDS-fueled panic at the time. And historians have supposed that Stoker viewed Dracula as the demonized Oscar Wilde after his prosecution for “the love that dare not speak its name”—which is to say, Stoker empathized with Wilde, to the degree that many historians believe Stoker himself was gay, and used his trial as inspiration for his horror tale. Coppola seems conscious of this connection (between blood disease, sexual uncertainty, religious punishment, and the deathly pursuit of someone who has been deemed doomed by God) and augments those themes in an indirect, perhaps even unintentional way throughout the film.

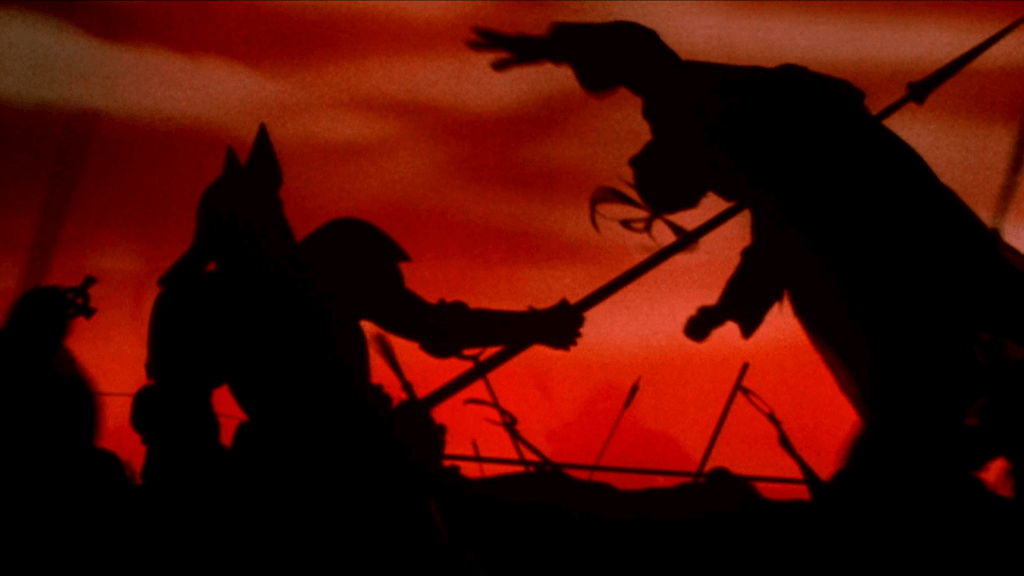

Relevant, if unconscious themes aside, Coppola’s story responds less to early ‘90s AIDS hysteria and, in fact, infuses the production with sensuality, enhancing its romanticized mannerisms through an omnipresent theatricality. When budget constraints forced Coppola to shoot on soundstages and special FX wizards told him modern technology couldn’t achieve the desired effects he wanted, Coppola made his most inspired decision and hired his son, Roman, to oversee second unit effects using old-fashioned techniques—not unlike the original Universal horror films like Dracula and Frankenstein, although enhanced with Coppola’s assured hand. Miniatures and models depict the Carpathian Mountains, Castle Dracula, and train sequences, whereas Victorian London is recreated with all the atmospheric detail Coppola could muster in a set piece. The opening sequence detailing Dracula’s battles in the Crusades appears as two-dimensional silhouettes shot against a matte painting; later, we see the image repeated in London’s cinematograph using miniatures cut to perspective, a gorgeous but basic approach. Simple tricks like double exposures, projected images, and film stock played in reverse achieve some of the film’s eeriest effects. And these are methods that have been used since cinema began.

Coppola’s most brilliant scenes in the film take place inside Castle Dracula, where the world does not behave as it should. At Borgo Pass, a demonic carriage driver outstretches his arm and grabs Harker from several feet beyond its reach, lifting its passenger into the carriage. When Harker arrives at the castle, the film’s Oscar-winning sound design delivers whispers and unintelligible screams coming from all around us (a top-notch audio system makes home viewings all the more unsettling). Coppola projects vampire shadows onto the wall, and they move independently of their owner, eager to break free of their master at any moment and strangle Harker. All around, the walls move closer, trapping Harker in his other-worldly environment where mice crawl on the ceiling, and the mirrors cast no reflection of the Count. Aside from the appearance of blue flame outside the castle, all of the film’s effects were created using in-camera techniques and no computers. Seeing films like this makes one ache for the days before CGI, when filmmakers still looked to the past for cunning ways to achieve movie magic. It took only Coppola’s enlivened willpower to return to these undeniably effective methods, which could be used today except for the lack of ingenuity of young filmmakers. Behind the artifice, Wojciech Kilar’s resounding score instills the film’s operatic sensibility into our bones with its reverberating sounds.

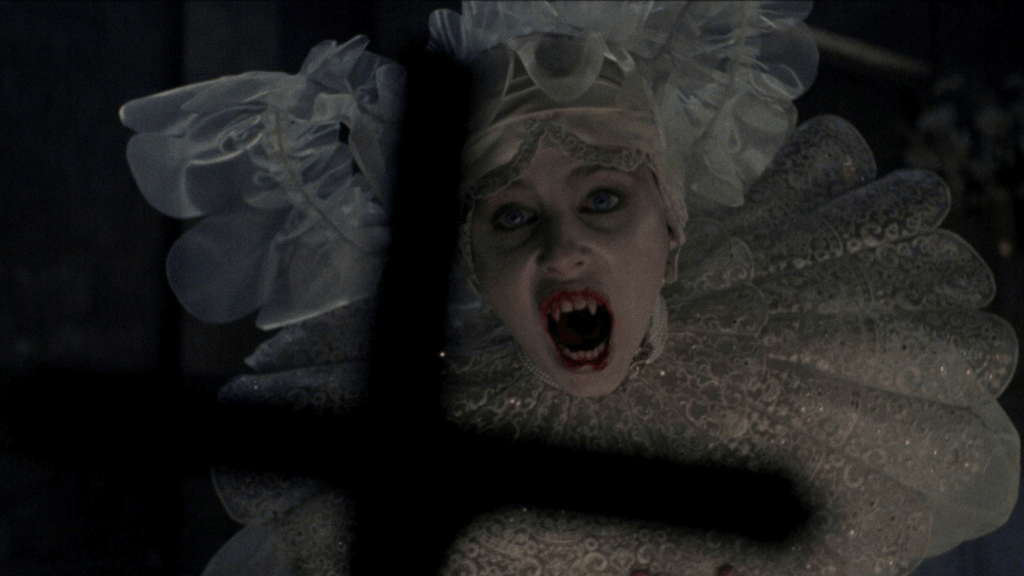

Amid the Oscars won for Bram Stoker’s Dracula, none were more deserved than those for costume design and makeup. Japanese designer Eiko captured elements of Kabuki Theater and Bela Lugosi mysticism in Dracula’s silky, crimson red robes, while the young warrior Dracula’s armor looks as though the skin was peeled from Vlad’s body to reveal the underlying musculature. Eiko would go on to design similarly styled garbs for visionary director Tarsem (The Cell, The Fall). Likewise, makeup crew Greg Cannom, Michèle Burke, and Matthew W. Mungle create frightening body suits for Oldman, from his aged Dracula face (complete with Kabuki-inspired buns in his hair and furry palms) to the wolf-man and bat-creature designs. Only Rick Baker has done better. That Oldman can perform in such elaborate costumes and still render the most chilling Dracula onscreen since Lugosi remains a testament not only to the costumes’ functionality but also to Oldman’s incredible, deeply articulated performance (in the film’s long list of larger-than-life portrayals). Regarded from a purely technical perspective, it’s impossible not to slather one’s affections on the film’s finely tuned veneer.

As for the story—the element against which the film’s detractors are most vocal—its cohesion does not come easily, but it rewards the audience for setting aside their reservations. In all truth, the story works better once the production’s splendid details have soaked into your memory through repeated viewings, allowing the romantic nature of the storytelling to take hold and the production’s palpable wonders to recede. With the enthusiasm of a film student hungry to use his vast knowledge of cinematic trickery, but with a master’s eye, Coppola constructed this elegant, stunning production that redefines Dracula by imparting humanity to its horror iconography. Blood and sensuality have very different meanings here than in typical vampire films, where necks are sucked and hearts are staked for entertainment value. Horror story and vampire tropes become components of this flawed masterpiece, whose grandiose staging embraces the bold imagery that made the legend what it is and integrates that boldness into every element of the production, resulting in an unparalleled and unforgettable telling of the Dracula drama in operatic terms.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review