Boyhood

By Brian Eggert |

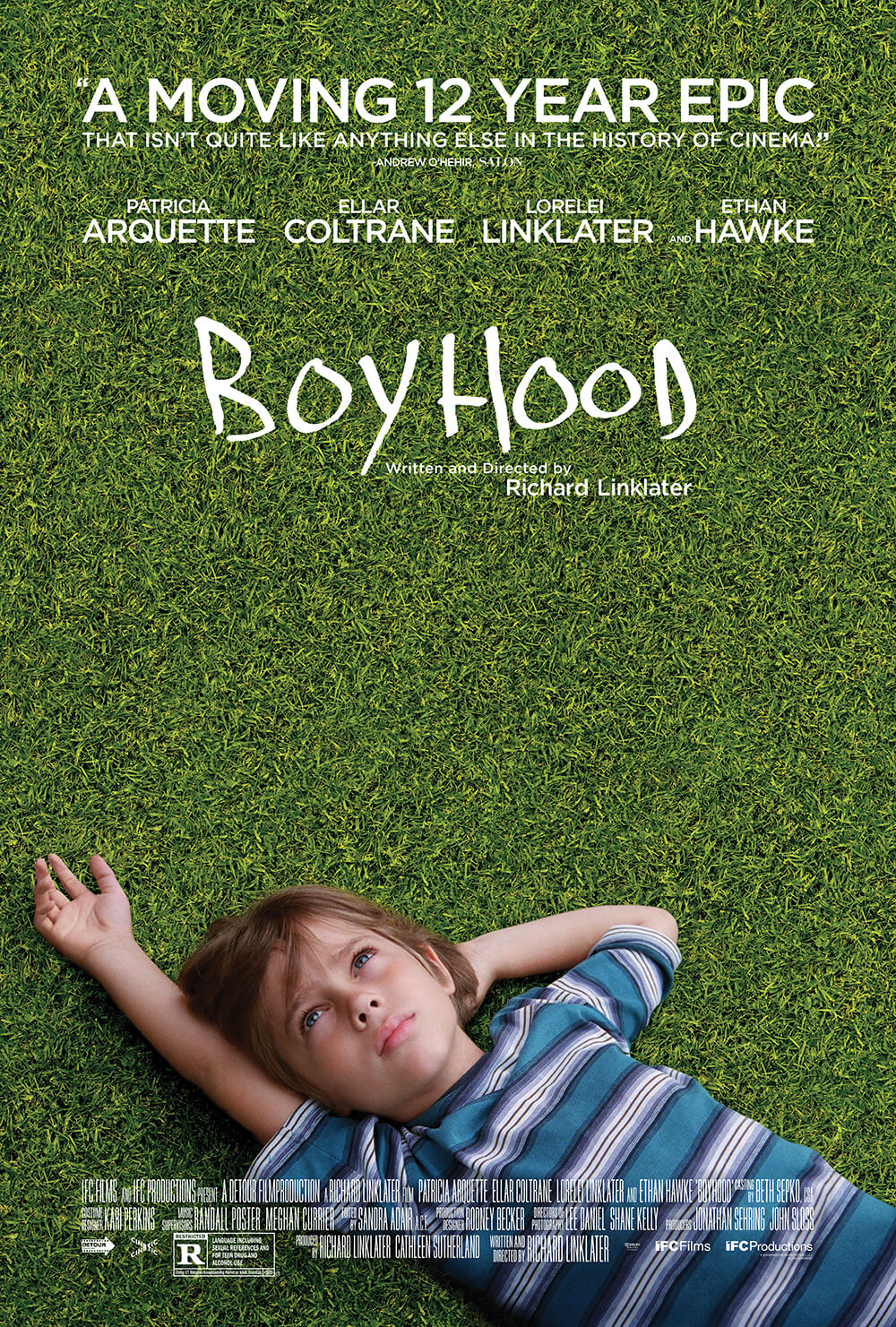

Ordinary life becomes monumental and extraordinary in Boyhood, Richard Linklater’s experiment in fiction that was shot between 2002 and 2013. Over those 12 years, Linklater’s camera carefully followed child actor Ellar Coltrane’s coming-of-age, shooting only 39 days’ worth of scenes over the years to chart the formation of his character from a 6-year-old boy to a young man bound for college with a fully developed identity. Alfred Hitchcock once told François Truffaut that drama is “life with the dull bits cut out,” but through the course of his film, Linklater resists the more melodramatic or artificial bits in favor of a simpler story about life and time, and it unfolds quite naturally. Along with his small cast of regulars, played by actors in a considerable creative commitment, Linklater revisited this fiction year after year, and therein achieved something rare in the realm of independent cinema.

The very notion of this project was a huge risk on Linklater’s part, primarily because his film is fiction and not, say, a documentary like Michael Apted’s ongoing Up series, which from 1964 onward has dropped-in every 7 years to chart the progress of 14 British citizens since their childhood. Some of Apted’s subjects have died or opted out of participating, whereas, if the same thing had happened to Boyhood, Linklater would have had a major gap in his production. Fortunately, Linklater was able to snag professional actors who were dedicated to the project, assigning Patricia Arquette and Linklater regular Ethan Hawke to the roles of Olivia and Mason Sr., the superbly played divorced parents of Coltrane’s Mason Jr. and his elder sister Samantha (Linklater’s daughter Lorelei). Audiences watch the youngsters grow into adolescents and young adults, while Arquette and Hawke age naturally with added wrinkles, weight, and other such signs of normal aging. The effect is not unlike the writer-director’s ongoing series of romances with Before Sunrise (1995), Before Sunset (2004), and Before Midnight (2013), where Hawke and actress Julie Delpy have grown as actors, their characters’ romance deepening over nearly twenty years.

Linklater’s approach to the story is straightforward and unblinking. He leaps without warning from one stage of development to the next, but the moments between the transitions aren’t dramatically significant enough to call them episodes. What’s most surprising about Boyhood is how effortlessly Linklater settles us into the material, yet how modest his story proves to be. Contained over an engrossing two-hours-and-forty-five-minute runtime are two drunken stepdads, some mild domestic disturbances, two moves, a first day at a new school, weekends with Dad, graduation, first love, and one hard breakup. These are ordinary-yet-major events in every life, often exploited for forced dramatic effect by any number of heavy-handed dramas, TV movies, or sitcoms. Thinking back now, I’m struggling to remember what happened during the film; even still, I feel that I know Mason. Indeed, these events never feel overwrought or exploitative; rather, just part of the ever-progressing scenery of Mason’s life.

More significant and memorable are the smaller moments for Mason, such as observing as his dad tries to talk to Sam about sex, conversations about Star Wars, or eating “commercial grade” s’mores on a camping trip. Mason attends the book release premiere of Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince and helps his dad post “Vote Obama” signs in neighbors’ yards for the 2008 election. But then some sharp contrasts occur as time progresses, such as when Mason’s voice has suddenly dropped with puberty and we realize how much he’s grown. His hair becomes greasy, his body lanky, and his completion blemished. He shoots his first gun with his religious-nut grandparents, receives his first camera as a young photographer, and suffers great disappointment when his dad sells the GTO that was promised to him for his 16th birthday (a promise Mason Sr. doesn’t remember). It might all be meaningless if not for Ellar Coltrane, who’s got undeniable presence and manages to grow up into a captivating young man before our eyes. Another stroke of luck for Boyhood; Coltrane could have grown to be a talentless bore.

Over the long (but never too long, never boring) runtime, Linklater makes us care for Mason and hope the best for him, and he does this by engaging in the kind of meaningful conversations that Linklater’s films have contained since his 1991 debut Slacker. The most fascinating aspect of Boyhood may be that, though Linklater may have sketched out the details of the technical production back in 2002, he allowed the script to evolve with its subject. While the director resolved to shoot on 35mm throughout for a consistent visional approach, the digital format would take over in the interim; but the content developed as Linklater came to know Coltrane as an introspective, artistic, and searching individual. The partnership couldn’t have worked out better, as Mason Jr. seems like a mellow character born from Linklater’s brand of conspiracy theorizing, anti-establishment, existentialist types whose conversations and abstract ideas are always entrancing.

Still, Boyhood consists of nothing more than a string of moments in a life through time, and Linklater is careful not to assign some grandiose meaning to everything we see, except to say that children are resilient and life must be lived without any prevailing need to answer the daunting “What does it all mean?” question. The experience of age and time on film has never been more profound, and only Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel series compares (Truffaut’s five films with actor Jean-Pierre Léaud began wonderfully in 1959 with The 400 Blows, and then gradually declined until their end in 1979 with Love on the Run). These passages in Mason’s life are charming, worrisome, funny, and touching, and by the end, the viewer must take stock just as one must do in moments of introspection or memory. Inside this beautiful, simple, and ambitious film is an almost documentary quality to truth that, despite the film’s lack of traditional plotting, engages the viewer in an indescribable way, and creates the closest thing to a real experience as few motion pictures ever have.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review