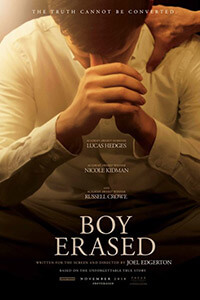

Boy Erased

By Brian Eggert |

In the wake of the United States’ escalating culture war, Hollywood has responded by embracing a series of based-on-a-true-story films designed to portray the downfalls of racism, gender discrimination, and heteronormativity. These films respond by demonstrating that our country has been here before and, in many cases, has overcome such narrow and prejudiced arguments. Whether they’re historical dramas (Hidden Figures, 2017), crowd-pleasers (Battle of the Sexes, 2017), or documentaries (RGB, 2018), their subject matter conveys that the battle for human rights continues and, at least in the examples provided, some measure of victory is possible. Their lessons serve as reminders of crimes that seem in the distant past but weren’t so long ago. Thus, it’s important to keep opposing, protesting against, and debating with those who attempt to enforce such excluding ideologies. However, the viewer must question what good such films do in the ongoing sociopolitical discourse. Is anyone on the side of racism, patriarchal rule, and binary gender roles watching these films and changing their minds? And if not, then aren’t they just preaching to the choir?

Boy Erased is the latest of this brood. It tells the story of Jared Eamons, an Arkansas college student who’s just figuring out that he’s gay. Based Garrard Conley’s 2016 memoir of the same name, the film depicts what occurs when Jared’s parents pull him out of college and place him into Love in Action, a gay conversion therapy center—a deeply Christian “refuge program” that tells Jared his “sexual sin and homosexuality fill a God-shaped void” in his life. Joel Edgerton, who wrote and directed the screen adaptation (his second effort, after 2015’s The Gift), appears as Victor Sykes, the program’s lead therapist, though Sykes holds no actual degrees or credentials that would make him qualified for such a role. Sykes argues that you cannot be born gay, that it’s a behavioral choice, and so, accompanied by his cruel enforcer (Flea), he teaches primarily male entrants to act manly, uncross their legs, and “fake it ‘till you make it.” The therapy culminates for each individual as they take “moral inventory,” a humiliating group forum designed so each person can expound their homosexual “sins” and, disturbingly, associate these feelings with anger.

Lucas Hedges plays Jared in a sensitive performance. The story finds him outed by a fellow college student to his parents—his doting mother Nancy (Nicole Kidman) and paterfamilias Marshall (Russell Crowe), a Baptist preacher who also runs a Ford dealership. Given the family’s entrenched belief that they are “normal” (Christian, white, heterosexual), Jared has long denied his feelings and impulses. In flashbacks, we see him resist sexual activity with his high school girlfriend, whom many assumed he would marry. The film’s nonlinear structure also shows us Jared’s early sexual experiences in college with young men, including a traumatic first encounter that would surely leave psychological scars and anxieties about exploring them further. And so, Jared’s coming out speech to his parents is achingly filled with lines like “God help me” and “I’m so sorry,” and his guilt over his feelings is both palpable and painful to behold.

Marshall is unwilling to allow his son to remain under his roof, as he believes that homosexuality is fundamentally against the teachings of The Bible (“There isn’t a question you can ask that can’t be answered by this book,” he preaches in a sermon). After seeking advice from his Baptist community leaders, Marshall insists that his son enter Love in Action, requiring Jared and Nancy to share a motel room nearby. Nancy, meanwhile, watches how Jared’s initial optimism about the program wanes as he returns from therapy each day—though, he’s unable to talk about his experiences because the program forbids those in it from discussing what goes on with outsiders. This means that Nancy never hears about the intimidation, mock funeral, or physical abuse that Jared’s group endures. Even so, she seems to recognize that it’s wrong somehow, but her role as a woman in a Southern family of this type leaves her without enough agency to protest. She overcomes that, eventually, leading to the tense climax.

Marshall is unwilling to allow his son to remain under his roof, as he believes that homosexuality is fundamentally against the teachings of The Bible (“There isn’t a question you can ask that can’t be answered by this book,” he preaches in a sermon). After seeking advice from his Baptist community leaders, Marshall insists that his son enter Love in Action, requiring Jared and Nancy to share a motel room nearby. Nancy, meanwhile, watches how Jared’s initial optimism about the program wanes as he returns from therapy each day—though, he’s unable to talk about his experiences because the program forbids those in it from discussing what goes on with outsiders. This means that Nancy never hears about the intimidation, mock funeral, or physical abuse that Jared’s group endures. Even so, she seems to recognize that it’s wrong somehow, but her role as a woman in a Southern family of this type leaves her without enough agency to protest. She overcomes that, eventually, leading to the tense climax.

Edgerton’s direction treats the material with an apt seriousness, but also a symbolic obviousness that drains Boy Erased of its emotional authenticity. Cinematographer Eduard Grau shoots in desaturated, flat colors that reflect the confusing period in Jared’s life. Editor Jay Rabinowitz creates a measured pace to the most dramatic scenes, delivering devastating moments with an affected slow-motion. Consider the brief scene where Jared, walking down the hall at school in slo-mo, finds himself moving against the flow of traffic—meant to evoke how Jared feels apart from the crowd. Sure enough, in the very next scene, Marshall tells Jared that his feelings about men “go against the grain of our beliefs and God himself.” Similarly, the score by Danny Bensi and Saunder Jurriaans sets the meaningful tone of every scene, along with some low-key songs, including “Revelation” by Troye Sivan—the Australian pop-singer who also appears in the film as Gary, one of Jared’s fellow convertees. When the film isn’t telegraphing how we should feel, Edgerton’s cast, himself included, delivers heartrending performances.

Boy Erased, though predictably made, tells a harrowing story with great empathy for Jared and his family. However, its reproach of conversion therapy camps and those who operate them is rather incomplete. In a postscript, titles explain that Sykes eventually left Love in Action and married a man. Now there’s an interesting character detail that goes completely unexplained, almost entirely without a hint in the dramatic context of the film. The film only briefly touches on Conley’s subsequent exposé of the economics and financial scamming of these places, and even less on who’s running them. Whether or not anyone’s mind will be changed by watching Boy Erased, who can say? The film’s dramatic structure conveniently situates Marshall as an epitome of heteronormative beliefs, given his status as a Baptist figurehead and community leader—he’s a beacon of his ideology, and he’s confronted by a human, social, moral, and familial conflict. And if anyone in the audience is going to be swayed, it’s by his arc. Marshall does not easily accept Jared’s sexuality, causing a rift in his family and marriage. Edgerton and his film ask the question: If your ideology demands that a family member is excluded, shunned, or banished because of their identity, then isn’t it time to take stock in your beliefs?

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review