Both Sides of the Blade

By Brian Eggert |

Note: This film was originally screened at the 2022 Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival and reviewed on May 15, 2022.

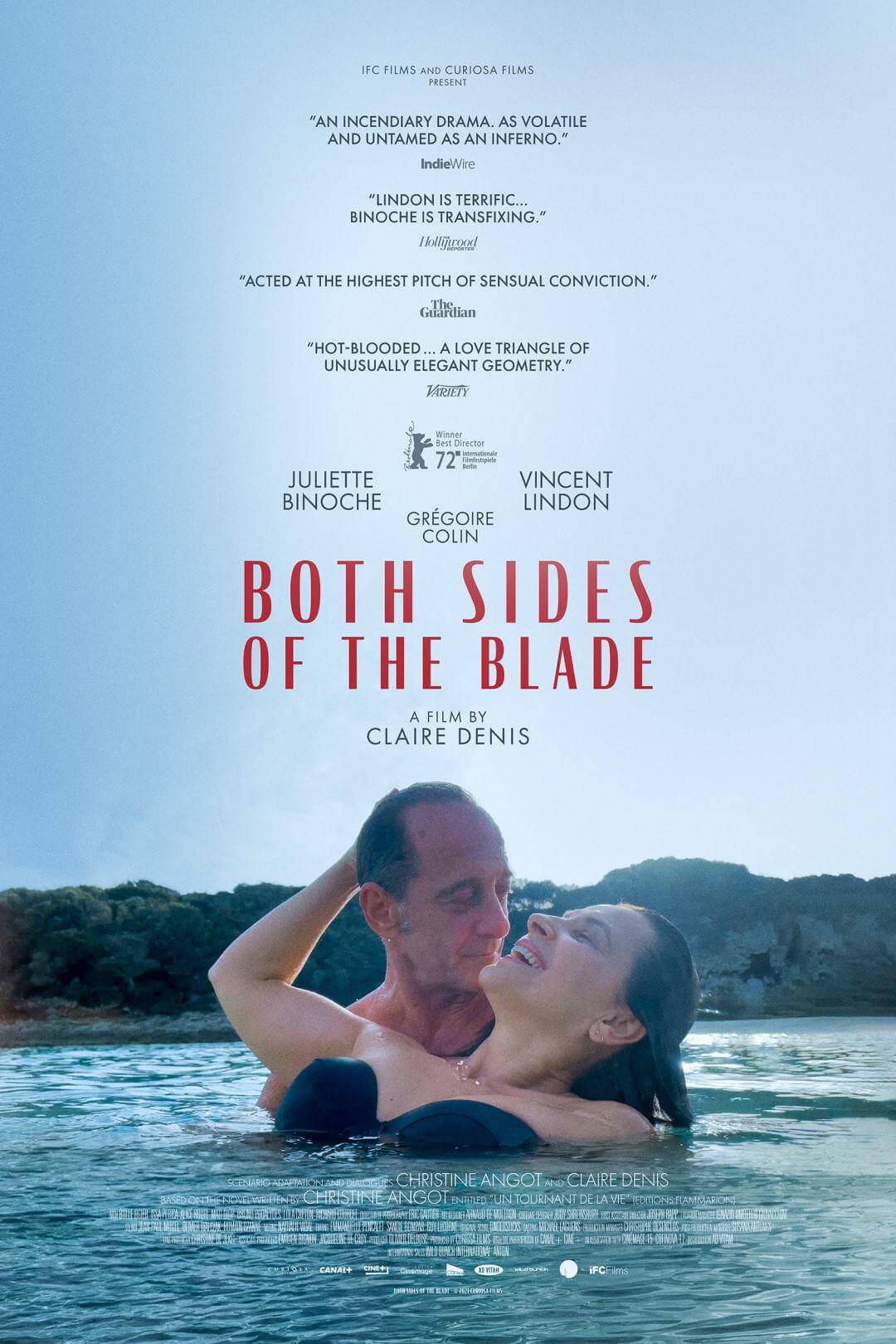

Claire Denis has a new film, and depending on where you live, its name varies. In France, where Denis shot the film under strict pandemic protocols, it goes by Avec amour et acharnement, which roughly translates to With Love and Determination. In the US, the distributors at IFC Films were poised to use the title Fire, while in other English-speaking territories, it’s known as Both Sides of the Blade. I saw the film at the Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival, and the festival’s literature called Denis’ latest Both Sides of the Blade, but confusingly, Avec amour et acharnement appeared onscreen with the translated subtitle Fire underneath. At the same time, the IFC Films website lists the title as Both Sides of the Blade as of this writing. Given the various handles, and the fact that another Denis film, The Stars at Noon, debuted at the Cannes Film Festival this year, one could be forgiven for thinking Denis has four new films hitting international theaters this year. Personally, I prefer Both Sides of the Blade as a title, for reasons I will explain in this review.

Whatever it’s called when you see it—and you should—Denis delivers what might be considered a minor work next to her recent monuments. Yet, it’s a powerful showcase for the talents of Juliette Binoche and Vincent Lindon. The director, often listed among the greatest living filmmakers today, has worked with both actors before: Binoche most recently on Let the Sunshine In (2018) and High Life (2019), and Lindon on Friday Night (2002) and Bastards (2013). The two luminaries of French cinema appear onscreen together for the first time in Both Sides of the Blade, an adaptation of Christine Angot’s 2018 novel Un tournant de la vie (A Turning Point in Life)—to throw another title at you. Denis has also worked with Angot before, on Let the Sunshine In. All of these details might make your head spin, but perhaps viewing this film while feeling tied up in knots about the various titles and linkages between artistic collaborators is a good way to engage with it. After all, it’s about a love triangle of shifting sympathies and redirected passions.

The film opens with Jean (Lindon) and Sara (Binoche) swimming in the ocean, adoring each other during a romantic getaway. Although they’re in a nine-year relationship, their love looks new and vibrant. Still, they have a complicated history: Jean, a former rugby player and ex-con for reasons never adequately explained, long ago left his wife for Sara. His ex-wife has since abandoned their son, Marcus (Issa Perica), and while Jean was away in prison, the court left Marcus with Jean’s at-her-wit’s-end mother, Nelly (Bulle Ogier). Sara, too, left someone behind for Jean—François (Grégoire Colin), her former lover who was also close friends with Jean. This loaded past comes rolling back into their lives one day when Sara glimpses François outside of her workplace, where she works as a radio journalist. Just the sight of François leaves her visibly shaken, and at her next encounter with Jean, she appears wounded, almost guilty. Her feelings boil to the surface when Jean and François go into business together, and the mere mention of François’ name, along with seeing him socially for Jean’s work, leaves Sara panicked by familiar emotions. “Here we go again,” she says to herself in the mirror.

Both Sides of the Blade unfolds almost like a domestic thriller; these characters have secret desires and risk exposing them. Soon Sara and François exchange texts and video calls. Jean suspects something is off, but inward and wary of confrontation, he does not express it. Even so, Jean’s criminal past looms over his incredible sensitivity. Will he snap? All the while, the music by the band Tindersticks, a regular collaborator with Denis, underscores the mounting tension. But one shouldn’t expect an Adrian Lyne or even Claude Chabrol film from Denis. She’s less interested in traditional dramatic archetypes and morality, offering instead a portrait of how love moves from one person to the next in unpredictable ways. The movement is volatile and destructive, creating in the same motion as it destroys. Still, Denis and Angot’s screenplay refuses to pass judgment on Sara or Jean for their behavior, regardless of how passive or, later, heated their relationship becomes. This is why Both Sides of the Blade, a title taken from a Tindersticks song, works better than Fire—which, to its credit, denotes the full-hearted passion that compels Sara to leave Jean for François, along with the ashen consequences of that choice. But Both Sides of the Blade acknowledges the lack of judgment on Denis’ part; rather, the title recognizes that relationships often sever, with love on either side.

Both Sides of the Blade unfolds almost like a domestic thriller; these characters have secret desires and risk exposing them. Soon Sara and François exchange texts and video calls. Jean suspects something is off, but inward and wary of confrontation, he does not express it. Even so, Jean’s criminal past looms over his incredible sensitivity. Will he snap? All the while, the music by the band Tindersticks, a regular collaborator with Denis, underscores the mounting tension. But one shouldn’t expect an Adrian Lyne or even Claude Chabrol film from Denis. She’s less interested in traditional dramatic archetypes and morality, offering instead a portrait of how love moves from one person to the next in unpredictable ways. The movement is volatile and destructive, creating in the same motion as it destroys. Still, Denis and Angot’s screenplay refuses to pass judgment on Sara or Jean for their behavior, regardless of how passive or, later, heated their relationship becomes. This is why Both Sides of the Blade, a title taken from a Tindersticks song, works better than Fire—which, to its credit, denotes the full-hearted passion that compels Sara to leave Jean for François, along with the ashen consequences of that choice. But Both Sides of the Blade acknowledges the lack of judgment on Denis’ part; rather, the title recognizes that relationships often sever, with love on either side.

But what’s in a title? The film contains some of the best acting from either of the two leads regardless of what it’s called. After last year’s Palme d’Or winner, Titane, Lindon once again plays a wounded and vulnerable character behind his imposing physical presence. He juggles a life that crumbles before us—not just with Sara, but also with his son in crisis and his close friend who commits a vile betrayal. The film seems to make him into an empathetic victim, until we remember that, years ago, Jean and Sara betrayed François in the same way. Still, when Jean eventually realizes the full extent of Sara’s betrayal, Lindon’s acting is jaw-droppingly authentic in its trauma and anger. The same is true of Binoche, who plays a character left gutted by her passion for François and her love for Jean, which both gnaw at her, leaving her almost schizophrenic—her two halves in denial of the other’s existence. When these two characters shatter all pretenses and confront each other in an unforgettable climactic scene, the performances mark a high point in these actors’ careers.

Both Sides of the Blade is part of a handful of projects ordered by Paris-based production company Wild Bunch International during COVID-19, and Denis, shooting on actual locations, doesn’t pretend the pandemic never happened as many productions have in recent years. But she also doesn’t make the pandemic a central plot device, as films such as Host (2020) or KIMI (2022) did. Rather, there’s a casual acceptance that some people wear masks, others don’t, and that’s part of everyday life. Other aspects don’t fit so smoothly. Denis is best known for films such as Chocolat (1989) and White Material (2009) that confront matters of race and colonialism, and those issues don’t play a vital role in the love triangle. But two scenes, one involving Lilian Thuram discussing Frantz Fanon on Sara’s radio show, and the other in Jean’s lecture about “white thinking” to his son, raise questions about their inclusion. Is Both Sides of the Blade somehow a metaphor for racial dynamics and power? If so, I don’t see it, and that leaves these scenes to feel out of place—even if their content proves intellectually compelling.

Regardless of occasional non-sequiturs, Both Sides of the Blade shows Denis’ command of her performers and their nuanced modulations of emotion and intention. (No wonder she received the Silver Bear for Best Director at the 72nd Berlin International Film Festival this year.) It’s a modest film in terms of the narrative ambition or novelty, and it even risks becoming an arthouse cliché—the inevitable moody French drama about a crumbling marriage. But there’s much to love here, including Denis’ treatment of familiar territory with enveloping camerawork by cinematographer Eric Gautier, who invades each scene to create emotional authenticity. Above all, Binoche and Lindon ennoble the film with their presence, giving open-hearted performances that bare the psychological and physical realities of sensual relationships in middle age. Ultimately, there’s no final word on the many facets and betrayals in their relationship, just a promise that when love ends, some kind of a fresh start begins.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review