Boston Strangler

By Brian Eggert |

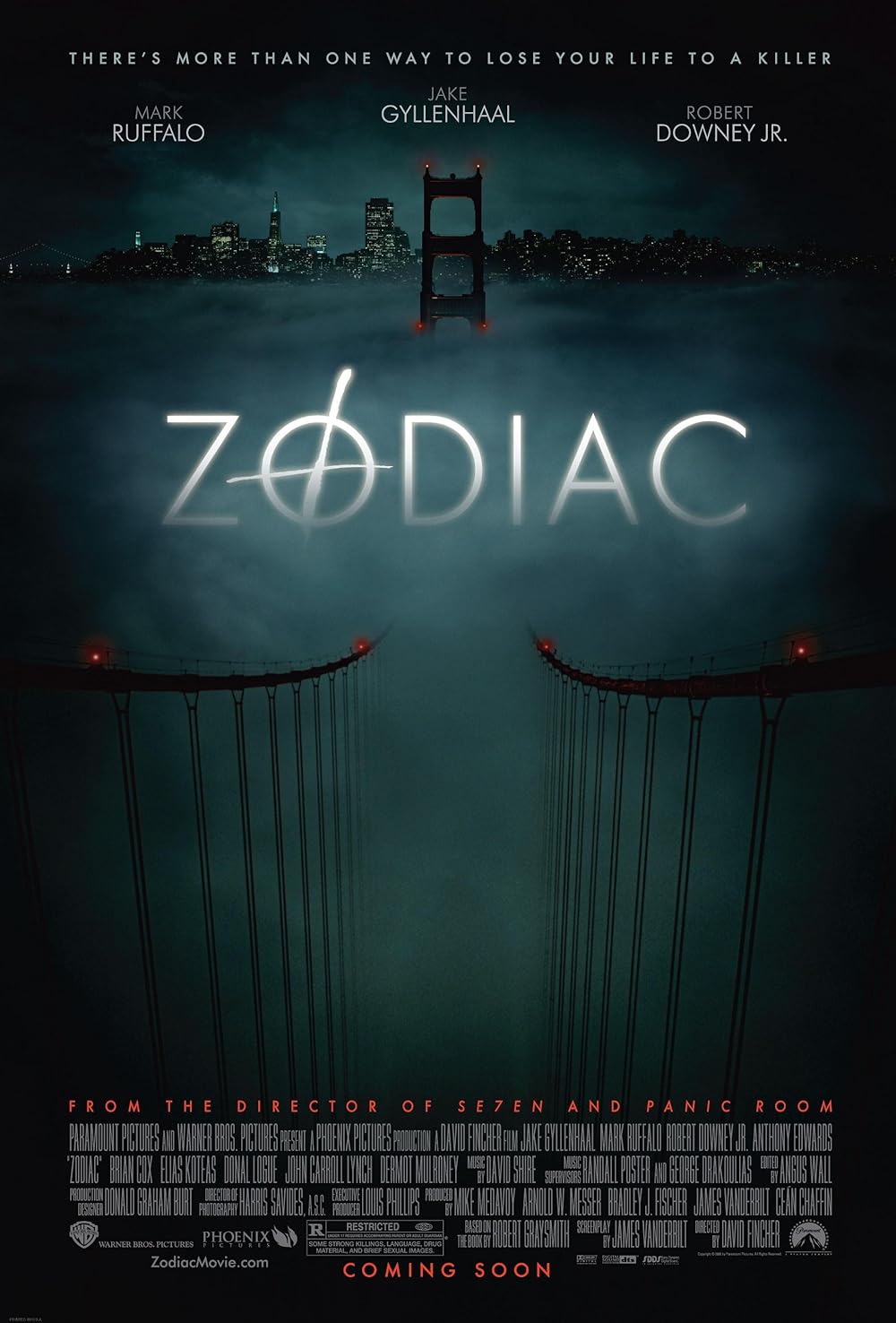

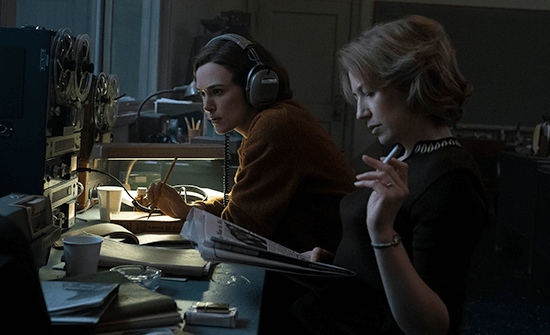

Slick production values and a terrific cast accompany writer-director Matt Ruskin’s Boston Strangler, an “Inspired by a True Story” account of the serial killer who murdered 13 women between 1962 and 1964. Aligned with the recent true crime craze in podcasts and documentaries, the film delves into the facts of a case that continues to invite speculation and theories about the murders. How fitting, since Ruskin’s last film, 2017’s Crown Heights, about the wrongful conviction of Colin Warner for murder, was adapted from the This American Life podcast. Given the subject matter, the film has every chance to connect with true crime enthusiasts. Perhaps best of all, the feature doubles as a portrait of women journalists who faced gender discrimination in their pursuit of the truth. Keira Knightley and Carrie Coon play Loretta McLaughlin and Jean Cole, the real-life investigative reporters for the Record American who broke the case and dubbed the killer the “Boston Strangler.” However, Ruskin’s polished treatment, produced by Ridley Scott’s company Scott Free, borrows a distracting amount of stylistic influence from David Fincher’s masterful Zodiac (2007). But if Ruskin was going to borrow, at least he borrowed from the best.

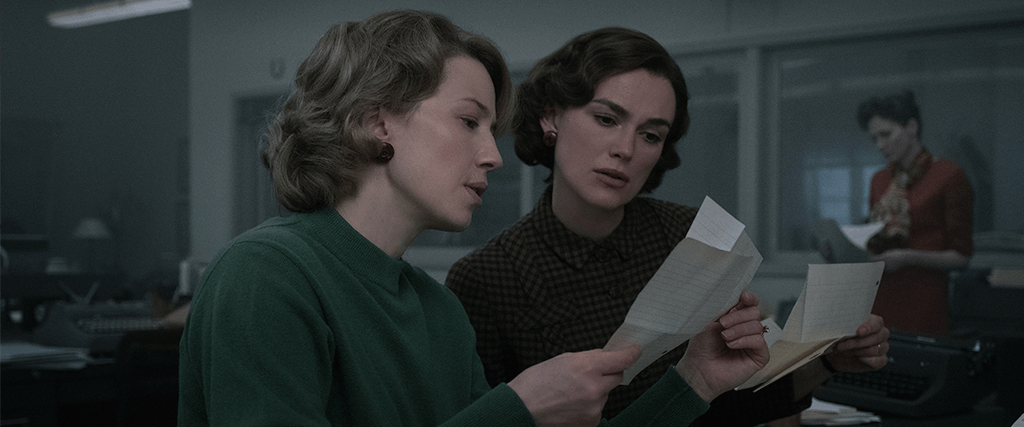

Unlike other films based on actual crimes, even Fincher’s superb Netflix series Mindhunter, Ruskin didn’t base Boston Strangler on previously published material. Usually, cinematic true crime stories draw from a nonfiction book or newspaper article, but Ruskin receives original screenplay credit here. Whether that speaks to the authenticity of his storytelling or not, and whether or not that matters, is open for debate. Regardless, after a brief prologue, the screen story opens in Boston at the Record American offices, where Knightley’s Loretta yearns for a position on the crime desk, but she’s stuck writing lifestyle columns on the latest toaster. Still, Loretta is the first to draw a connection between three killings of women in their apartments, as each victim was tied down and choked to death, then left with a stocking tied around their neck in a “decorative” double-hitched knot—this after a knock on their apartment door, claiming the super has ordered a new coat of paint. Even so, Loretta struggles to earn her editor’s (Chris Cooper) blessing on the story, and after she does, he teams her with a more experienced crime reporter, Jean. Although initially worried about having to compete, Loretta soon finds an ally in Jean, who teaches her how to cover the crime beat.

Almost immediately, viewers will notice how closely Ruskin and cinematographer Ben Kutchins parrot Fincher’s visual treatment of Zodiac and Mindhunter. Aesthetically, the films share many similarities, from the amber-hued color palette to composer Paul Leonard-Morgan’s brooding score to the shots composed of gliding camerawork. It’s an effective and atmospheric approach, to be sure, but no less naggingly derivative. Ruskin’s script deploys many of the themes found in Zodiac, such as various police departments refusing to work in tandem, therefore missing out on crucial details that inform the case. There’s even a scene when Loretta explores a lead and finds herself in an unnerving space, which may or may not belong to the killer, but nonetheless demands an immediate get-out-of-there reaction—the mirror of a scene from Zodiac featuring Jake Gyllenhaal in a creepy, damp basement. The average viewer may not notice or care about such similar stylistic choices, but Fincher fans may question the originality of Ruskin’s technique.

Telling the story from the perspective of women journalists in the 1960s allows the director to explore two genres at once: the procedural, and a more intimate drama about women overcoming personal challenges and sexism. For instance, when Loretta’s initial story upsets the chauvinist police commissioner (Bill Camp), he accuses her of flirting with interview subjects and claims she didn’t introduce herself as a reporter. Later, the paper forces Loretta and Jean to put their photographs on their bylines, believing two good-looking women—referred to as “girl reporters”—will sell more papers. When their reporting leads to several revelations missed by investigators, defended by the newspaper as “good men” despite their sloppy work, they face harsh criticism as journalists and women. The exception is the cynical homicide detective, Jim Conley (Alessandro Nivola), who befriends Loretta and offers important information for her articles. Meanwhile, both Loretta and Jean have husbands and multiple children, and their time away from home puts a strain on their families. Morgan Spector plays Loretta’s husband, James, who seems supportive enough, until Loretta’s career becomes too much of an inconvenience for their home life.

Telling the story from the perspective of women journalists in the 1960s allows the director to explore two genres at once: the procedural, and a more intimate drama about women overcoming personal challenges and sexism. For instance, when Loretta’s initial story upsets the chauvinist police commissioner (Bill Camp), he accuses her of flirting with interview subjects and claims she didn’t introduce herself as a reporter. Later, the paper forces Loretta and Jean to put their photographs on their bylines, believing two good-looking women—referred to as “girl reporters”—will sell more papers. When their reporting leads to several revelations missed by investigators, defended by the newspaper as “good men” despite their sloppy work, they face harsh criticism as journalists and women. The exception is the cynical homicide detective, Jim Conley (Alessandro Nivola), who befriends Loretta and offers important information for her articles. Meanwhile, both Loretta and Jean have husbands and multiple children, and their time away from home puts a strain on their families. Morgan Spector plays Loretta’s husband, James, who seems supportive enough, until Loretta’s career becomes too much of an inconvenience for their home life.

Knightley gives a convincing performance as Loretta, who’s just realizing what it means to pursue her professional ambitions, while Coon is an excellent presence as Jean—a hardened reporter who’s been through what Loretta is just starting to experience. Along with the impressive ensemble already mentioned, David Dastmalchian, ever typecast as weirdos and psychopaths, plays Albert DeSalvo, the prime suspect. Elsewhere, those familiar with the case will have plenty to consider in Ruskin’s take, which, unlike other movies about the Boston Strangler, introduces some thorny details. The material was covered in the highly fictionalized The Strangler (1964), followed by the somewhat more credible and well-cast The Boston Strangler (1968), starring Tony Curtis, Henry Fonda, and George Kennedy. As with most dramatizations, Ruskin’s film shouldn’t be seen as a document of historical fact. He takes poetic license in some areas and commits to running theory in others. Yet, it’s the most convincing feature film about the subject.

Following a trend of respectable mid-budget projects dropped onto Hulu by 20th Century Studios, Boston Strangler offers a handsome production that would have been even more immersive on the big screen. Ruskin’s screenplay and aesthetic choices may seem overly familiar at times, but the storytelling and performances remain so compelling that only purists will dismiss the result. Moreover, the similarities between this case and the Zodiac killer may reveal common behaviors and institutional problems among police units that, rooted in tradition and perhaps foolish pride, they could not overcome at the time. Ruskin doesn’t take many of the risks that Fincher does—which elevate Fincher’s film above the average serial killer procedural into a sprawling and paranoid study of obsession—but nevertheless, there’s not a dull moment in Boston Strangler’s two-hour runtime. Whether viewed as a serial killer yarn or an inspirational story about women overcoming gender biases, the film remains close to its antecedents but delivers a solid drama that will appeal to today’s amateur sleuths and true crime enthusiasts.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review