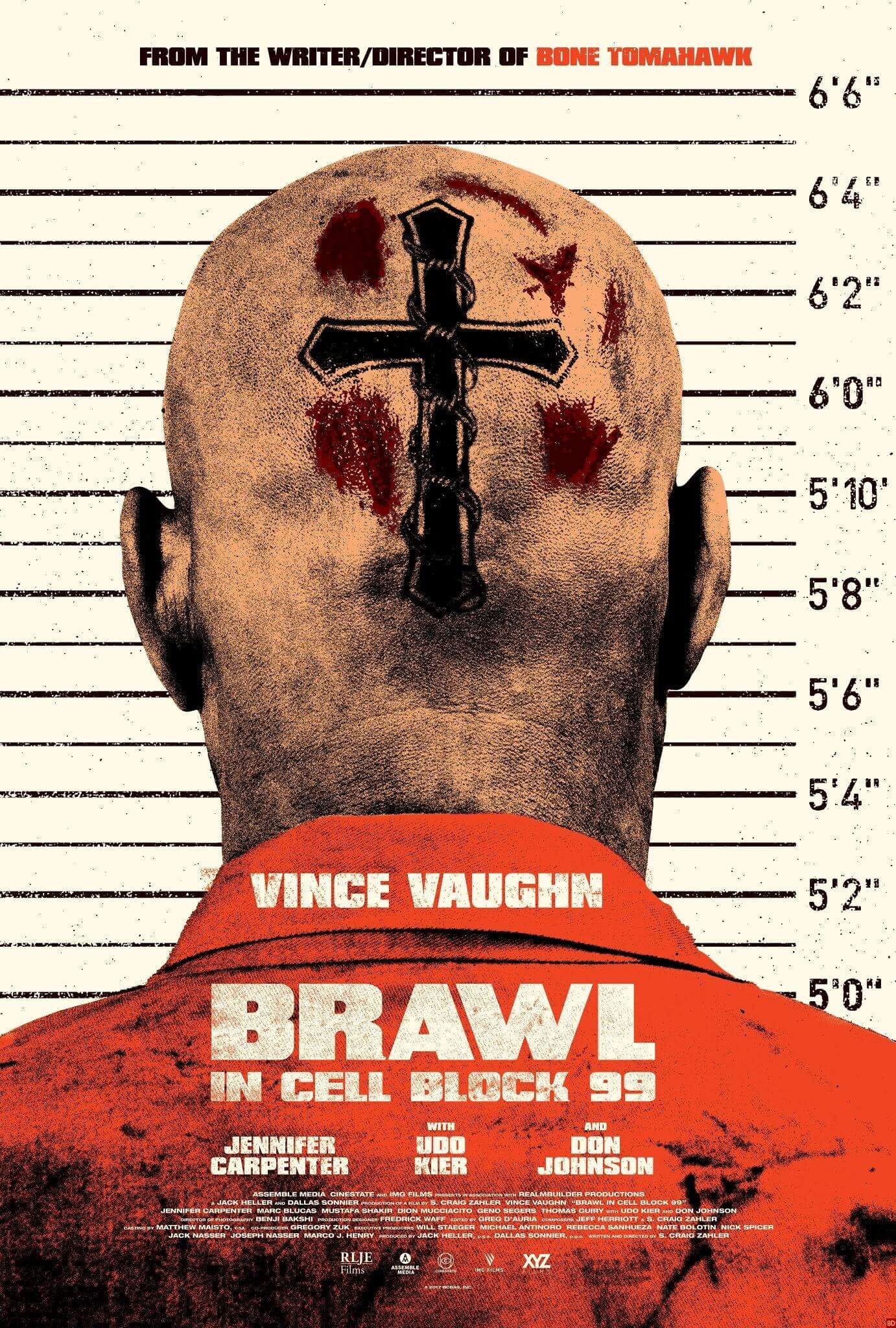

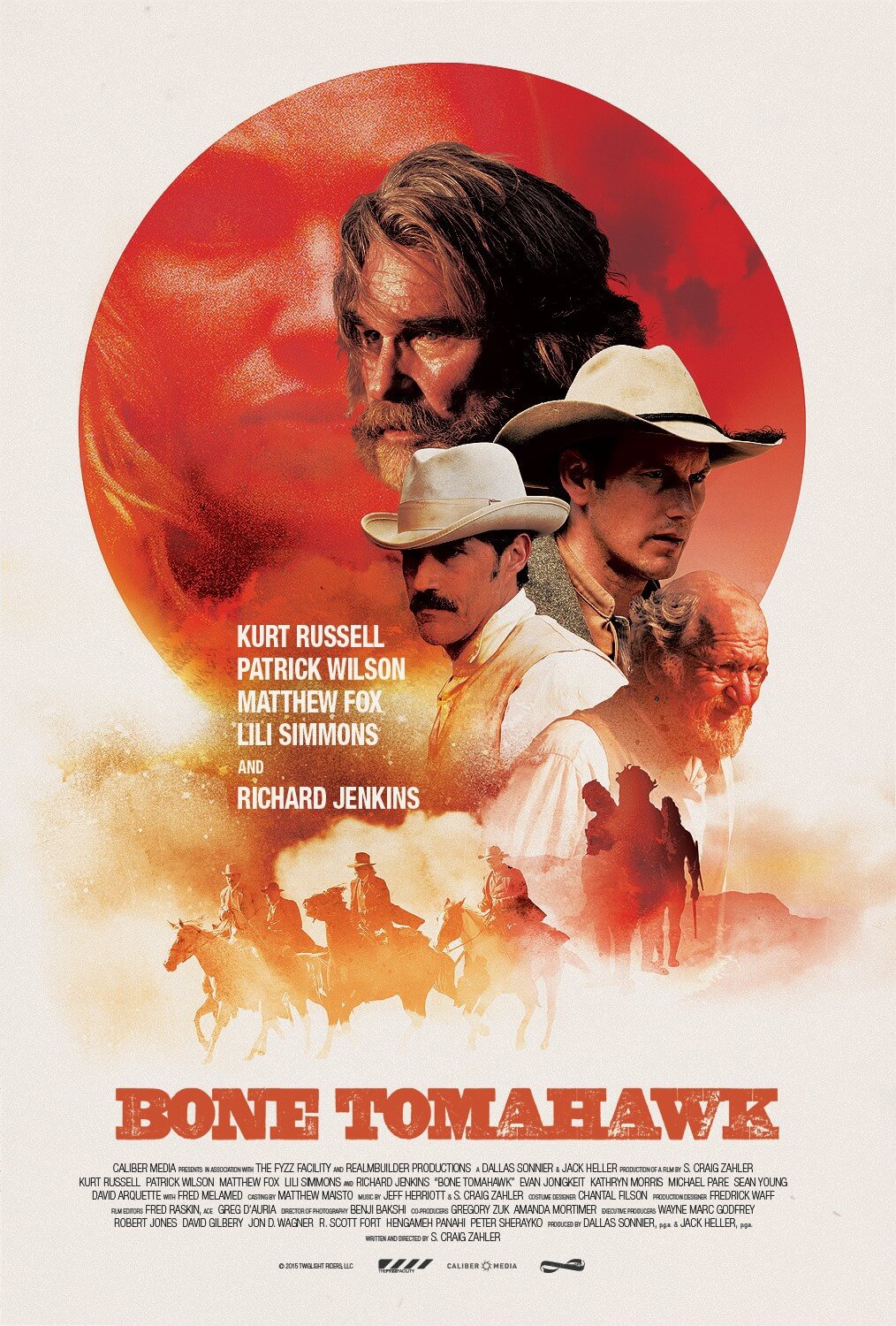

Bone Tomahawk

By Brian Eggert |

Ambling at a steady, measured pace, the hero characters of Bone Tomahawk chew scenery and effect boundless gravitas in writer-director S. Craig Zahler’s debut feature. Their doomed journey to save a kidnapped woman echoes John Ford’s The Searchers (1956), while Zahler’s unique dialogue has a historically accurate and idiosyncratic charm that evokes Charles Portis’ 1968 novel True Grit (later made into a classic Western with John Wayne, then again in Joel and Ethan Coen’s superior version starring Jeff Bridges). Without winking at its audience, the picture moseys along on a lengthy and engrossing quest populated by endearing characters, leading to a bloody showdown with a band of cave-dwelling cannibals. Despite the potential for a B-movie fringe quality, Bone Tomahawk ever-maintains its formal integrity in the classical Western style, while Zahler still manages to terrify his audience in an effective marriage of genres.

Long in development, this modestly budgeted cult-favorite-in-the-making was announced back in 2012, although scheduling and budgetary issues required some ironing-out. Zahler waited to shoot his original story until his ideal leading man, Kurt Russell, was ready. Russell, a longtime Western aficionado who starred (and secretly co-directed) one of the more recent best, Tombstone (1993), also stands as a cult figure for many. After all, he appeared in a handful of titles for John Carpenter (Elvis, The Thing, Escape from New York, Big Trouble in Little China, and Escape from L.A.). He also proved his man’s-man quality in dozens of actioners and fun comedies in the 1980s and 1990s. Moreover, he demonstrated his excellent impersonation of John Wayne in Quentin Tarantino’s car-slasher Death Proof (2007). So it would seem Russell was born to be the leading man in a horror-Western.

Russell stars as Franklin Hunt, Sheriff of Bright Hope, a small and relatively peaceful town on the frontier. Though the year remains unknown, it’s sometime after 1891, as spied on a tombstone, and so the wildest part of the West has been tamed. Nevertheless, when a suspicious drifter (David Arquette, costar of Ravenous, another cannibal-Western) comes into town, Hunt engages him and sets off a regrettable series of events by shooting him in the leg and dragging him to jail. Elsewhere, Patrick Wilson’s Arthur O’Dwyer lies in bed with a nasty leg break, having fallen during some roof repair. When his wife, Samantha O’Dwyer (Lili Simmons), gets called to the Sheriff’s station to look over the wounded drifter, she, a deputy, and the drifter go missing overnight, presumably taken by Indians. But as a local Native American points out, the raiders are actually an isolated band of cannibalistic troglodytes, fierce and deadly, best to be avoided. And yet, Zahler carefully avoids a standard ‘Cowboys vs. Indians’ setup and acknowledges the political incorrectness of such a conflict today. Though a Native American man points out to Sheriff Hunt, “Men like you would not distinguish them from Indians,” the director makes it clear these cave dwellers are monstrous.

Warned that any rescue mission would surely end in bloodshed for all involved, Sheriff Hunt does not hesitate to lead a drive to rescue Samantha and the others. From here, Bone Tomahawk eases into a steady rhythm when Sheriff Hunt and his three compatriots head out. Beside him is “backup deputy” Chicory, played by Richard Jenkins in a part reminiscent of Walter Brennan’s reliable old codger roles (see Rio Bravo or Red River). Matthew Fox plays a vain, expert Indian-killer named Brooder, whose rigid, dashing sensibilities are not without their tragic elements. To be sure, these characters may seem like tropes, yet they each carry a full measure of gravitas developed over the course of their journey. Some of the best scenes in Bone Tomahawk involve stellar acting and deeply human exchanges, often in the form of bickering and petty squabbles, among these performers. Jenkins is particularly great. Consider a scene late in the film, where Chicory prattles on about a flea circus that came to town. He admits other flea circuses probably feature motorized contraptions, but this one seemed real; the others confirm it was, if only to bring the somewhat simple-minded Chicory a moment of joy.

Warned that any rescue mission would surely end in bloodshed for all involved, Sheriff Hunt does not hesitate to lead a drive to rescue Samantha and the others. From here, Bone Tomahawk eases into a steady rhythm when Sheriff Hunt and his three compatriots head out. Beside him is “backup deputy” Chicory, played by Richard Jenkins in a part reminiscent of Walter Brennan’s reliable old codger roles (see Rio Bravo or Red River). Matthew Fox plays a vain, expert Indian-killer named Brooder, whose rigid, dashing sensibilities are not without their tragic elements. To be sure, these characters may seem like tropes, yet they each carry a full measure of gravitas developed over the course of their journey. Some of the best scenes in Bone Tomahawk involve stellar acting and deeply human exchanges, often in the form of bickering and petty squabbles, among these performers. Jenkins is particularly great. Consider a scene late in the film, where Chicory prattles on about a flea circus that came to town. He admits other flea circuses probably feature motorized contraptions, but this one seemed real; the others confirm it was, if only to bring the somewhat simple-minded Chicory a moment of joy.

Another director would have cut this scene, as it takes place in the middle of the cannibal-laden finale, but Zahler is far more interested in Western characters than mindless bloodshed. It’s the same reason he allows the runtime to extend beyond two hours; there are too many great moments with the foursome heroes to cut a single scene over a fire or on horseback. Russell’s grizzled beard and mustache, soon to be featured in Tarantino’s upcoming Western The Hateful Eight, and easy, confident mannerisms contain an endless amount of character, without need for expositional backstory. Zahler also spends a considerable amount of time dealing with Arthur’s broken leg, the difficulty of every step, and how it slows down the rescue party, all wonderfully acted by Wilson. Zahler wants us to savor every instant of the mannered dialogue between these men. He wants us to lose ourselves in cinematographer Benji Bakshi’s earthy lensing, take in production designer Fredy Waff’s excellent sets, and appreciate the simplicity of Chantal Filson’s costumes.

These engrossing details compile into a film that’s very much about the intentionally paced journey. However, when the cannibal violence finally arrives in the last half-hour, it comes in savage bursts that will make you gasp and cover your mouth in terror over some of the most unsettling sights you’ve ever seen in a film. At one point, a man is cleaned and prepped for eating, and the scene out-grosses anything seen in Eli Roth’s recent cannibal fare The Green Inferno, in part because the film establishes a mood of seriousness early on. Besides, these cannibals are monstrous and scary, easily the most memorable movie monsters to reach screens in some time. Rather than speaking, they’ve implanted boney horns into their neck, and when they shriek out it sounds like a possessed Velociraptor. They carry sharp bone weapons, pierce their flesh with animal tusks, and paint their bodies white. All male warriors, we see the unfortunate fate of their females: blinded and shackled, the females’ legs are removed, turning them into nothing more than baby-making vessels.

Crafted with a bronzed look and shot on the Paramount Ranch, the film’s visual authenticity also has a novelistic quality that instills everything onscreen with, as suggested by the aforementioned comparison to Portis’ book, a distinctiveness from other Westerns. Though Zahler and Jeff Herriott composed a folk score, more often than not there’s no score at all, allowing us to get into the repetitive sound of galloping hooves, footsteps, and Chicory’s charmed ramblings. (Again, the journey’s the thing.) Based on its ‘Cowboys vs. Cannibals’ setup alone, it would be easy to dismiss this film as nothing more than a cult yarn, but Zahler’s evident formal control transforms it into a pleasure for which there should be no guilt. I loved Bone Tomahawk from start to finish. It contains unconventional, memorable dialogue and doesn’t treat itself like low-brow entertainment; rather, it’s a grim but Fordian homage, made with an uncommon confidence for a first-time director.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review