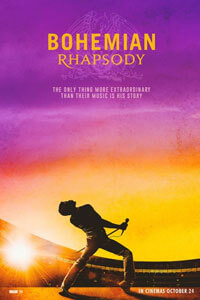

Bohemian Rhapsody

By Brian Eggert |

“Bohemian Rhapsody,” a Queen song of shifting, dreamy styles and mystical lyrics that has a way of getting stuck in your head for days at a time, was released in 1975 to mostly dismissive reviews. At nearly six minutes, it was considered an indulgent step away from the popular glam rock of the 1970s, while critics couldn’t quite pinpoint, or were altogether uninterested in its blend of opera, guitar rock, and woeful ballad, and thus dismissed it. Years later, it became more popular and widely embraced, and it’s easy to understand why it took so long for listeners to deconstruct. Setting aside the usual 24-track analog tapes provided by studios, Queen used an incredible 180 overdubs on the song, which featured several harmonic and rhythmic shifts, and it took weeks to record. It was experimental, arranged with complex transitions, and defiant of formula—none of which are ways I would describe the film Bohemian Rhapsody, about the rock legends Queen, and their magnetic frontman, Freddie Mercury.

A scene about midway through the 2-hour-and-15-minute biopic demonstrates what kind of portrait director Bryan Singer has made. Having spent weeks producing their album A Night at the Opera, the band presents the outcome to EMI executive Ray Foster (Mike Myers), who explains that “Bohemian Rhapsody” isn’t the kind of song that inspires teenagers to listen while driving around in their cars at night. Of course, the SNL alum Myers starred in Wayne’s World, a comedy that featured a rocking lip-synch performance in a car by a group of teens. Although Myers helped put “Bohemian Rhapsody” back on the charts in 1992 just a few short months after Mercury’s death, and even introduced the song to a new generation, the moment is a winking, unnecessary nod. It’s illustrative of Singer’s approach, which is less about contextualizing the oddity and artistic ambitions of Queen in the rock scene, and more about concentrating on surface-level anecdotes better summarized on the band’s Wikipedia page.

Bohemian Rhapsody opens with a brief introduction to Farrokh Bulsara, who later renames himself Freddie Mercury in one of his many flamboyant impulses of self-reinvention. Played by Rami Malek in an exuberant, show-stealing performance, Mercury is a young Londoner born in Zanzibar to Parsi parents, a stern father (Ace Bhatti) and loving mother (Meneka Das). He quickly joins a college band, winning over guitarist Brian May (Gwilym Lee) and drummer Roger Taylor (Ben Hardy) with an impromptu audition, explaining he was born with four extra incisors, which may give him a distinct overbite but also affords a wider vocal range. They add bassist John Deacon (Joseph Mazzello), call themselves Queen, write some iconic songs, tour the world in a corny montage, and make millions. Mercury, though initially married to Mary Austin (Lucy Boynton), explores his sexuality in gay bars and with multiple partners, including the shady Paul Prenter (Allen Leech), who feeds off of the band’s success. Fueled by drugs, alcohol, and a pervasive sense of loneliness, Mercury has some nasty encounters with the invasive press, isolates himself from his bandmates, and has that moment when he inevitably coughs blood into a rag. After learning he has AIDS, Mercury seeks redemption; he gets the band back together to participate in the massive Live Aid charity concert in 1985, ending the film on a high note.

Screenwriter Anthony McCarten, who penned the bland scripts for The Theory of Everything (2014) and Darkest Hour (2017), follows the conventional rise-and-fall blueprint of every film about a musician from The Doors (1991) to the widely celebrated Walk the Line (2005). But it’s an outmoded recipe satirized in Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story (2007), which should have meant an end to this bland narrative trajectory. Alas, no. McCarten’s paint-by-numbers script was mostly directed by Singer, himself a surface-over-substance presence behind the camera, before being replaced by producer Dexter Fletcher after two-thirds of the filming was complete. Together, McCarten and the directors hit the typical beats. All the familiar elements are here, and they’re self-consciously directed and sentimentalized. When Mercury realizes that Paul has betrayed him, the scene takes place in the pouring rain. Because the film wants to engage the masses, it limits its depiction of gay sex and nudity (hence the PG-13 rating). Worse, there are scenes like this: Early in the film, Mercury plays a few notes of the piano melody from “Bohemian Rhapsody,” and then smiles to himself and tells Mary, “I think it has potential.” Such moments, along with dull in-the-recording-studio sequences that show how the band wrote songs like “We Will Rock You” to interact with their audience in a way few other bands ever could, seem unnecessary and hardly engage the film’s audience.

Screenwriter Anthony McCarten, who penned the bland scripts for The Theory of Everything (2014) and Darkest Hour (2017), follows the conventional rise-and-fall blueprint of every film about a musician from The Doors (1991) to the widely celebrated Walk the Line (2005). But it’s an outmoded recipe satirized in Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story (2007), which should have meant an end to this bland narrative trajectory. Alas, no. McCarten’s paint-by-numbers script was mostly directed by Singer, himself a surface-over-substance presence behind the camera, before being replaced by producer Dexter Fletcher after two-thirds of the filming was complete. Together, McCarten and the directors hit the typical beats. All the familiar elements are here, and they’re self-consciously directed and sentimentalized. When Mercury realizes that Paul has betrayed him, the scene takes place in the pouring rain. Because the film wants to engage the masses, it limits its depiction of gay sex and nudity (hence the PG-13 rating). Worse, there are scenes like this: Early in the film, Mercury plays a few notes of the piano melody from “Bohemian Rhapsody,” and then smiles to himself and tells Mary, “I think it has potential.” Such moments, along with dull in-the-recording-studio sequences that show how the band wrote songs like “We Will Rock You” to interact with their audience in a way few other bands ever could, seem unnecessary and hardly engage the film’s audience.

Rami Malek, best known from TV’s Mr. Robot, is the reason to watch Bohemian Rhapsody. He inhabits Mercury, though he bears only a faint resemblance to the real thing. (Malek has green eyes; Mercury’s were dark brown. Malek’s frame is much slimmer than Mercury’s wider shouldered physique.) But the actor impressively replicates Mercury’s energetic stage presence—he clearly had a blast every second he was on stage—and the singer’s uncanny ability to command a crowd of thousands, as shown in the film’s most compelling moments of Queen in concert. While the rest of the cast is serviceable, Malek demonstrates a physical commitment to recreating Mercury’s showy, performative streak, rich with sexuality and a bravado that sends him moving and dancing about the stage. Of course, the filmmakers use Mercury’s actual voice for the singing scenes. But Malek’s performance is so convincing that, along with our pure enjoyment of the songs themselves, we forget we’re watching an actor. The film’s most self-reflexive moment appears early, where Queen appears on television for the first time, and the producers demand that Mercury lip-synch. After some objections, the band concedes, and Mercury gives the most natural performance imaginable under the conditions, much the way Malek does throughout.

Bohemian Rhapsody alternates between an exceedingly bland dramatic shorthand about Queen and Mercury’s life, and several long concert scenes that cannot help but enthuse the viewer. It’s to the film’s benefit that it ends with Queen’s monumental Live Aid performance, recreated almost in its entirety as the final act. As Malek performs to a distractingly CGI crowd, we can feel ourselves being manipulated with this final high-note before the obligatory end titles summarize Mercury’s remaining few years and his battle with AIDS. And even though we see the strings being pulled, the final performance is emotional, fun, and resoundingly satisfying. Watch the real thing sometime, and you’ll appreciate how well this sequence is reconstructed here. If only it were preceded by two hours that did more than predictably dramatize major events in Mercury’s life or state the fact of Queen’s existence as a rock phenomenon. In the end, Bohemian Rhapsody leaves you wanting to listen to the band’s music, find a more intricate portrait of their lives, and learn more about the complexities of Freddie Mercury.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review