Reader's Choice

Bo Burnham: Inside

By Brian Eggert |

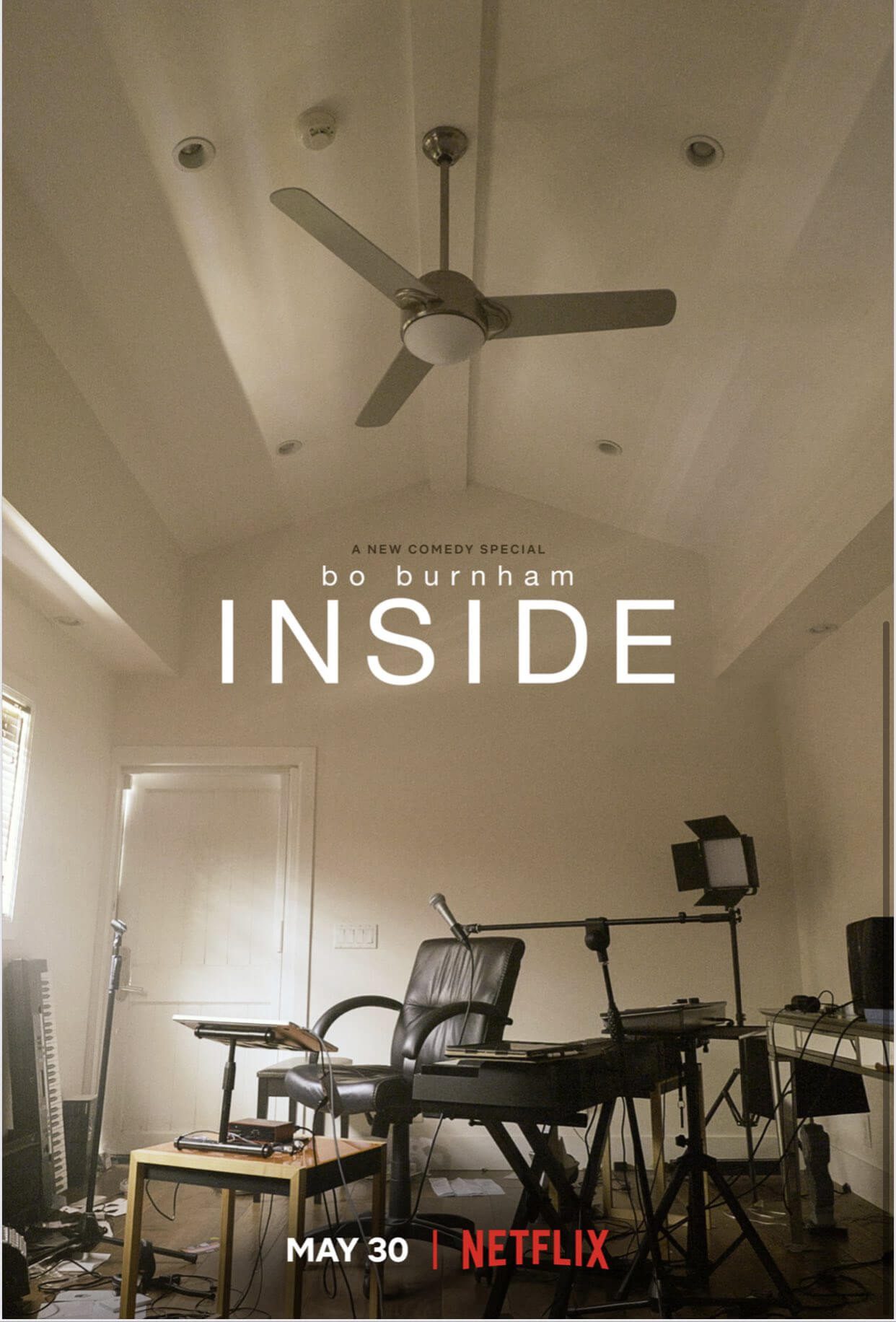

If you remember life before the internet—before social media, online performativity, smartphone addiction, twenty open tabs on your browser, and corrosive virtual communities—you’re part of a shrinking minority. Most people under the age of fifty maintain some level of online addiction. It’s challenging to avoid the near-constant stimulation from notifications, memes, viral videos, and doom-scrolling the never-ending news cycle. Having to live in quarantine for COVID-19 has only exacerbated things, leading to destructive behavior and hopefully some self-reflection about how much time we’re spending on our devices and what exactly we get out of our relationship with the internet. Bo Burnham’s new comedy special for Netflix, Inside, explores many of these themes, a regular topic in his comedy and music. But it’s also a creative act of self-reflection about life as a performer in lockdown. Shot over a year during the pandemic, Burnham wrote, directed, and edited the special himself, using one room in his small guest house as a stage. The result, filled with catchy songs and hilarious commentary, feels personal, fractured, repetitive, self-conscious, and often relatable.

For Burnham, who earned his start making YouTube videos before transitioning into live comedy, comedy specials, acting, and filmmaking, having an audience means validation as an entertainer and even a human being. But for obvious reasons, he doesn’t have an audience for Inside. It’s not the usual comedy special where a performer stands on a stage with a microphone and tells jokes. Instead, he fills the 87-minute runtime with comic scenes and a procession of alternatively goofy and depressing songs performed with homespun lighting effects and visible production equipment everywhere. He ventures into creative and observational territory with songs about FaceTiming his mother or a white woman’s Instagram posts. In my favorite song from the special, called “Welcome to the Internet,” he sings a carnivalesque tune like a barker selling a freak show, offering “a little bit of everything all of the time.” Most of his songs involve some critique of our digital lives, from Jeff Bezos to sexting to feeling insecure yet driven to put ourselves out there.

However, Burnham doesn’t avoid the elephant in the room; he confronts his declining mental state in quarantine, his desperate need for attention, yet his self-hatred for needing that attention. He needed to make Inside, but at the same time, creating it fuels the very online culture he critiques. Of course, the irony is that Burnham probably wouldn’t have a career if not for the internet. He seems well aware of his place in the system as a “content” creator, and what’s more, a white guy commenting on these trends when the world has had enough of his particular perspective. Burnham engages in a self-critique of his need for attention and the way he perpetuates an ultimately destructive system. What’s so compelling about Inside is that his self-awareness reflects our own conscious state of being trapped in an endless loop—of the internet, in our homes, from our perspectives—and unable to escape. He performs because he must; it’s an addiction like any other. He creates just as we can’t help but check our social profiles, forums, or news hubs with frequent regularity, despite knowing that we’re addicts and would probably be better served by logging off altogether. One of his more symbolic comic bits that gets to the root of these obsessions involves a recursive reaction video to a reaction video to a reaction video, and so on, in a continuous loop until he resolves to stop.

Burnham’s last live performance was in 2016. In the five years since, he made the film Eighth Grade (2018), which in no small way deals with online performance and finding oneself, and took the occasional acting role (see last year’s Promising Young Woman). He confesses in Inside that he hasn’t returned to the stage because he kept having anxiety attacks. Convinced he should work to overcome his anxiety, he started preparing to come back in January 2020. “And then the funniest thing happened,” he muses. The pandemic stalled his healing journey, leaving him to recoil into his unhealthy cycle. Burnham is a comedian who, not unlike Maria Bamford or Pete Davidson, performs comedy for a living yet suffers from various mental conditions, depression and anxiety most prominently so. There’s a nagging desire to put himself out there, coupled with a resentful awareness that he needs validation yet fears rejection. It’s a complex dynamic that Inside investigates, although never really confronts beyond acknowledging the inner conflict.

Burnham’s last live performance was in 2016. In the five years since, he made the film Eighth Grade (2018), which in no small way deals with online performance and finding oneself, and took the occasional acting role (see last year’s Promising Young Woman). He confesses in Inside that he hasn’t returned to the stage because he kept having anxiety attacks. Convinced he should work to overcome his anxiety, he started preparing to come back in January 2020. “And then the funniest thing happened,” he muses. The pandemic stalled his healing journey, leaving him to recoil into his unhealthy cycle. Burnham is a comedian who, not unlike Maria Bamford or Pete Davidson, performs comedy for a living yet suffers from various mental conditions, depression and anxiety most prominently so. There’s a nagging desire to put himself out there, coupled with a resentful awareness that he needs validation yet fears rejection. It’s a complex dynamic that Inside investigates, although never really confronts beyond acknowledging the inner conflict.

Another aspect of Inside entails its making. Burnham includes shots where he tests—and sometimes drops—his equipment, experimenting with different lighting techniques and camera angles. We see his facial hair grow longer and his eyes get darker, and the wear becomes more evident on his face. With each new song, presented chronologically as he recorded them, we experience his process and mental decline. The special becomes increasingly sad and odd. At one point, he appears on the floor, wrapped in a blanket, his head resting on a pillow next to a microphone. He remarks, “Maybe the flattening of the entire subjective human experience into a lifeless exchange of value that benefits nobody except for, um, you know a handful of bug-eyed salamanders in Silicon Valley, maybe that as a way of life forever, maybe that’s not good.” He openly questions the vehicle for his brand of entertainment and thus why he’s doing this. The answer is that he must. Why else does one choose to sing a song about an existential crisis in his tighty whities?

Surprisingly, there are few if any direct remarks about the pandemic—the reason he’s forced to make Inside in utter isolation. How appropriate, since many of the special’s concerns transcend the pandemic, which has magnified them. Doubtless, had the pandemic never occurred, the filmed-before-an-audience special that replaced Inside would have addressed many of the same themes, if not so pointedly. Still, like watching a documentary, it’s vital to remember that every choice Burnham makes has been added intentionally. When he appears haggard, his eyes look red and puffy, admits he hasn’t showered, or breaks down crying, those are creative inclusions and, in some ways, performative choices that contain equal measures of honesty and construction. They’re part of the show but also part of Burnham’s life. He needs this, and he admits to wondering what he’ll do in isolation when it’s finished. “That means I have to just live my life,” he says, as though that would be so bad. How much of that life will be online?

Inside debuted on Netflix (the most appropriate venue for it, really) at the end of May 2021. This review comes after more than two months of online discourse and lionization about its observations, but only the rare critique of its apparent contradictions. Burnham’s special, which also had a brief run in movie theaters (a wholly inappropriate way to consume it), perpetuates the very problems it identifies. Burnham asks, “Is it necessary to express every opinion you have? Can anyone shut the fuck up about any single thing?” At this, we must ponder if Burnham’s self-awareness and meta-ness are enough to absolve him from his hypocrisy. But since each of us complains about the hollowness of online culture and yet continues to take part, each of us whines about how Netflix is a junkheap of streaming content yet will probably watch season four of Stranger Things in a single sitting, and each of us knows the dangers of social media yet probably spends more time on such platforms than we’d like to admit, it’s difficult to fault Burnham for falling into the same trap that ensnares us all.

(Note: This review was originally suggested, commissioned, and posted on Patreon. Thanks for your support, Dustin!)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review