Reader's Choice

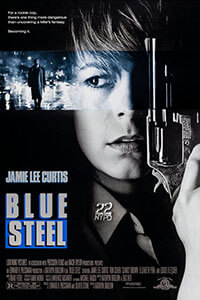

Blue Steel

By Brian Eggert |

From the title sequence of Blue Steel, when the camera explores the vaginal cylinder chambers and phallic barrel of a handgun up close—in a similar tactic used by Julia Ducornau on automobiles in Titane (2021)—the film signals its interest in gender and identity. Kathryn Bigelow’s third film as director feminizes the traditionally masculine genre of the urban cop thriller, following a female rookie cop who, fresh out of the police academy, finds herself stalked by a lunatic Wall Street trader. Upon its release in 1990, the rise of feminist film theory and female police offers on the streets made the film a product of a moment, but it still proves ripe for analysis and deconstruction today. Bigelow reconsiders movies driven by masculine archetypes, such as Dirty Harry (1971) or To Live and Die in L.A. (1985), deploying a gender inversion that, while intellectually challenging from a gender studies perspective, fails to achieve many of the hallmarks of a good thriller. Ultimately, Bigelow undoes her main character by bending the narrative to meet the demands of an overloaded gender contrast and genre critique, often in unnaturally stuffed and downright absurd ways. The result is a film that functions better as an academic case study than a compelling thriller with behaviors that make sense on logical or emotional grounds.

Blue Steel launches into action with a lone cop responding to a domestic disturbance. Cinematographer Amir Mokri’s kinetic handheld camera follows as Megan Turner (Jamie Lee Curtis), weapon drawn, maneuvers down a hallway, getting closer to the sound of shouting and violence. Finally, Turner kicks the door open and finds herself facing down a man holding a gun on a woman, telling Turner that he’ll shoot. When he seems poised to fire, Turner takes him down, but the perp’s hostage reaches for a gun and shoots her. Fortunately, it’s all an exercise, which Turner has failed. “In the field, you gotta have eyes in the back of your head,” warns an instructor. Nevertheless, she graduates and earns a spot in the NYPD, at a time when Hollywood often portrayed New York as a cesspool of crime perpetrated by scumbags and slimeballs—and the city had the crime rate to match (making the production’s on-location shooting all the more immersive). Indeed, on Turner’s first day, she spies an armed and strung-out thug (Tom Sizemore) robbing a grocery store. He turns to shoot when she confronts him, but she fires first and blasts him through the window. At the same time, the gun falls from the robber’s hand, and a witness, Eugene Hunt (Ron Silver in a committed performance, for better or worse), takes the gun and sneaks away from the scene. Apparently, Turner ignored the lesson from the failed exercise that opens the film.

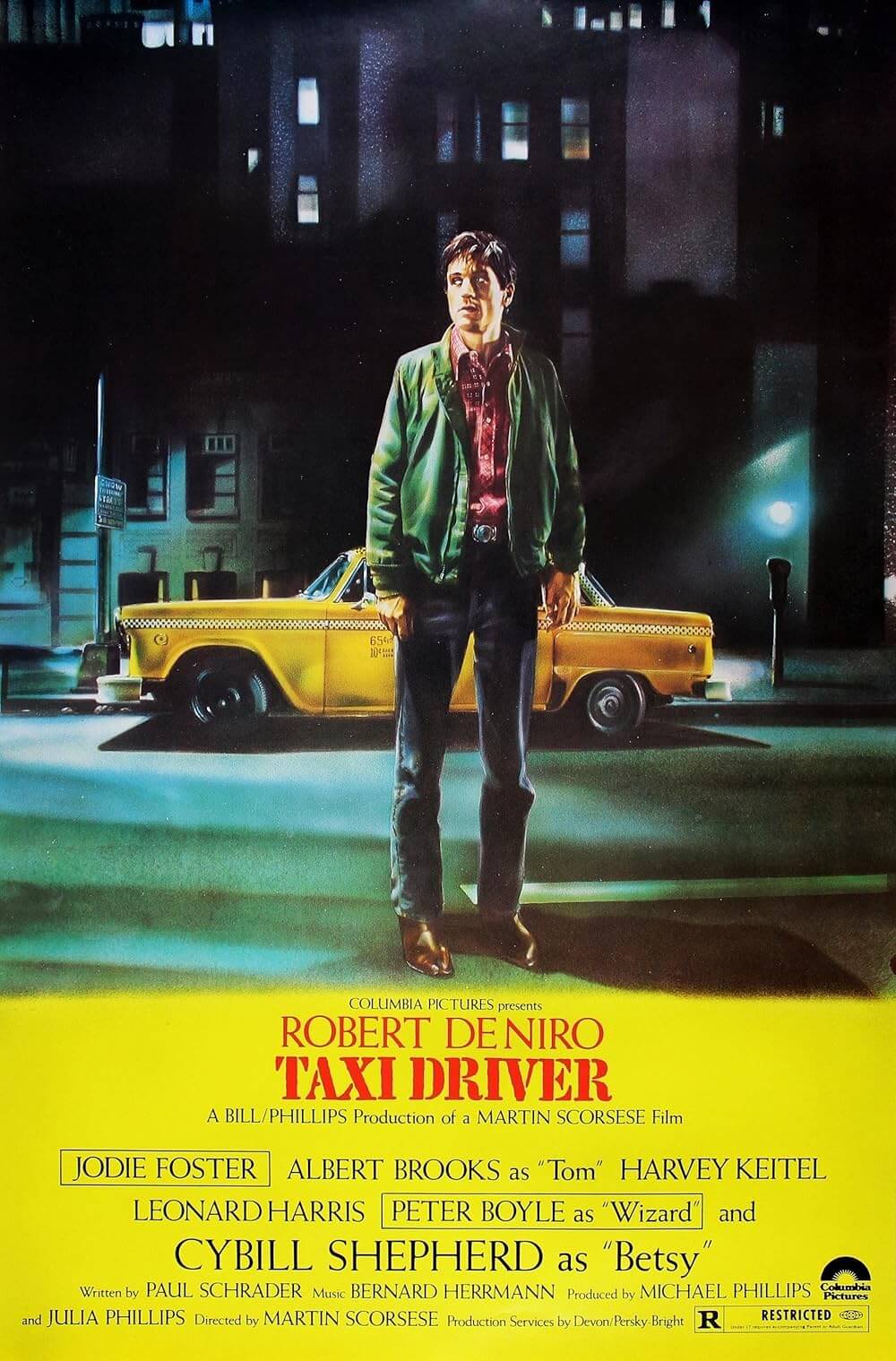

While Turner goes on suspension pending an investigation into the shooting, which appears as though she killed an unarmed man given that the gun disappeared from the crime scene, Eugene snaps. The wealthy trader succumbs to gun fetishism in ways recalling Robert De Niro’s role in Taxi Driver (1976)—complete with a scene admiring himself with a gun in the mirror, along with familiar dialogue about the chaotic noise of the city. After seeing Turner shoot the thug, Eugene becomes obsessed with her. He engraves her name onto bullets and then shoots random people in the city, earning the nickname “the .44 caliber killer”—the same label given to serial killer David Berkowitz in the 1970s, an evident influence. Turner’s name on the shells prompts her superior (Kevin Dunn) to reinstate her—as a detective no less, in an unlikely development—to investigate the killings in which she is somehow involved, under the oversight of seasoned detective Nick Mann (Clancy Brown). Meanwhile, Turner meets Eugene on the street in a touch of dramatic irony. They begin dating with a series of fancy dinners and even a helicopter ride—scenes that become increasingly tense when juxtaposed against moments of Eugene’s mental decline: He talks to himself, refers to himself as a god, and kills a sex worker before virtually bathing in her blood.

Bigelow, who comes from a background in film theory at Columbia University, eagerly seizes the opportunity to investigate how Turner’s identity as a female cop clashes with other aspects of her life, deepening a straightforward serial killer yarn with elements of a family drama and sexual thriller. Turner comes from a working-class family with a drunken father (Philip Bosco) and a battered mother (Louise Fletcher). Aspects of her romantic life find her not only dating the prime suspect but also sleeping with her partner. Even her best friend (Elizabeth Peña) gets pulled into Turner’s identity as a cop when the killer targets her. Unfortunately, Bigelow’s approach proves almost didactic in how she and co-writer Eric Red fold every aspect of Turner’s life and femininity into her role as a police officer. What is more, they actively comment on the genre by engaging in a dialogue with—and in some ways subverting—the traditional cop thriller. For instance, Turner uses her role as a cop to resolve her father’s abuse of her mother, emasculating him with an arrest before eventually returning him home, humbled. But when Eugene invades Turner’s life, Bigelow and Red take the intermingling of masculine and feminine, cop and criminal, personal and professional to disturbing extremes: In a confrontation after Turner and Mann sleep together in a steamy scene, Eugene shoots Mann and rapes Turner, attacking her position as a cop and woman. Eventually, the upending of every facet of Turner’s life becomes conspicuous, if not downright laughably convenient from a screenwriting perspective.

Bigelow, who comes from a background in film theory at Columbia University, eagerly seizes the opportunity to investigate how Turner’s identity as a female cop clashes with other aspects of her life, deepening a straightforward serial killer yarn with elements of a family drama and sexual thriller. Turner comes from a working-class family with a drunken father (Philip Bosco) and a battered mother (Louise Fletcher). Aspects of her romantic life find her not only dating the prime suspect but also sleeping with her partner. Even her best friend (Elizabeth Peña) gets pulled into Turner’s identity as a cop when the killer targets her. Unfortunately, Bigelow’s approach proves almost didactic in how she and co-writer Eric Red fold every aspect of Turner’s life and femininity into her role as a police officer. What is more, they actively comment on the genre by engaging in a dialogue with—and in some ways subverting—the traditional cop thriller. For instance, Turner uses her role as a cop to resolve her father’s abuse of her mother, emasculating him with an arrest before eventually returning him home, humbled. But when Eugene invades Turner’s life, Bigelow and Red take the intermingling of masculine and feminine, cop and criminal, personal and professional to disturbing extremes: In a confrontation after Turner and Mann sleep together in a steamy scene, Eugene shoots Mann and rapes Turner, attacking her position as a cop and woman. Eventually, the upending of every facet of Turner’s life becomes conspicuous, if not downright laughably convenient from a screenwriting perspective.

Scholar Cora Kaplan described Blue Steel as an “explicitly deconstructive and analytic project embedded into a mass-market film.” True enough. However, the film actively undercuts Turner to achieve this, much to the narrative’s detriment. After all, Bigelow starts the movie with a training sequence that finds Turner failing, followed by a scene where she dresses for graduation in a uniform that appears two sizes too big, like a child playing pretend. Later, when Turner busts Eugene after he reveals himself as a gun-obsessed wacko, she fails to gather any evidence that would make her arrest stick. Later still, she threatens to kill Eugene in front of his attorney (Richard Jenkins), which is probably not a smart move. And when staking out Central Park with Mann, Turner handcuffs Mann to the steering wheel to exact revenge on Eugene on her own, but Eugene gets the upper hand and nearly kills Mann. Indeed, in the basic terms of a police procedural, Turner makes idiotic decisions that would frustrate even novice genre aficionados, forcing us to wonder how she graduated. Along with other noted examples that show Turner making bad choices on the job, these moments suggest she’s not so much overcoming gender stereotypes as railroading through them with retributive violence. In the climax, she assaults a fellow officer to take his uniform and gun, and then she hunts down Eugene for a shootout in the street. The film ends abruptly just after she kills Eugene, causing the viewer to wonder if she will be arrested for attacking a fellow officer.

All the while, Blue Steel raises questions about female empowerment in a patriarchal society by portraying uneven power distributions by gender. When Turner first dons the police uniform and wields a gun, she bears the traditional symbols of authority, but not the masculine appearance or sense of empowerment that usually inhabits them. Note when Turner’s best friend introduces her to a man who asks, “You’re a good-looking woman. Beautiful, in fact. Why would you want to be a cop?” He does not respect her power as a police officer, nor does he see her as a viable romantic partner given her authoritative occupation, and so she feels disempowered by his rejection. Alternatively, when Eugene steals the weapon from the robbery crime scene, he goes mad with male power, forcing his victims to witness his power by having them look him in the eyes, thus seeing their own demise. He also tries to assert his dominance over a woman (Turner) who holds that same power—first by wooing her, then destroying her career, raping her, and killing her loved ones. Finally, Turner regains control by mastering the phallic power that has corrupted Eugene’s mind by filling his chest with bullets. Symbolically speaking, Bigelow uses traditionally masculine genre conventions to uncover a feminist perspective. Curtis, known for her androgynous beauty, occupies this defiant role and helps Bigelow demystify or redirect the phallic power associated with guns. As a result, Bigelow weaponizes the genre by what critic Jude Schwendenwien called “playing the game by the boys’ rules”—delivering an actionized scenario about a woman preserving her authority in a patriarchal system that constantly deflates her power with violence.

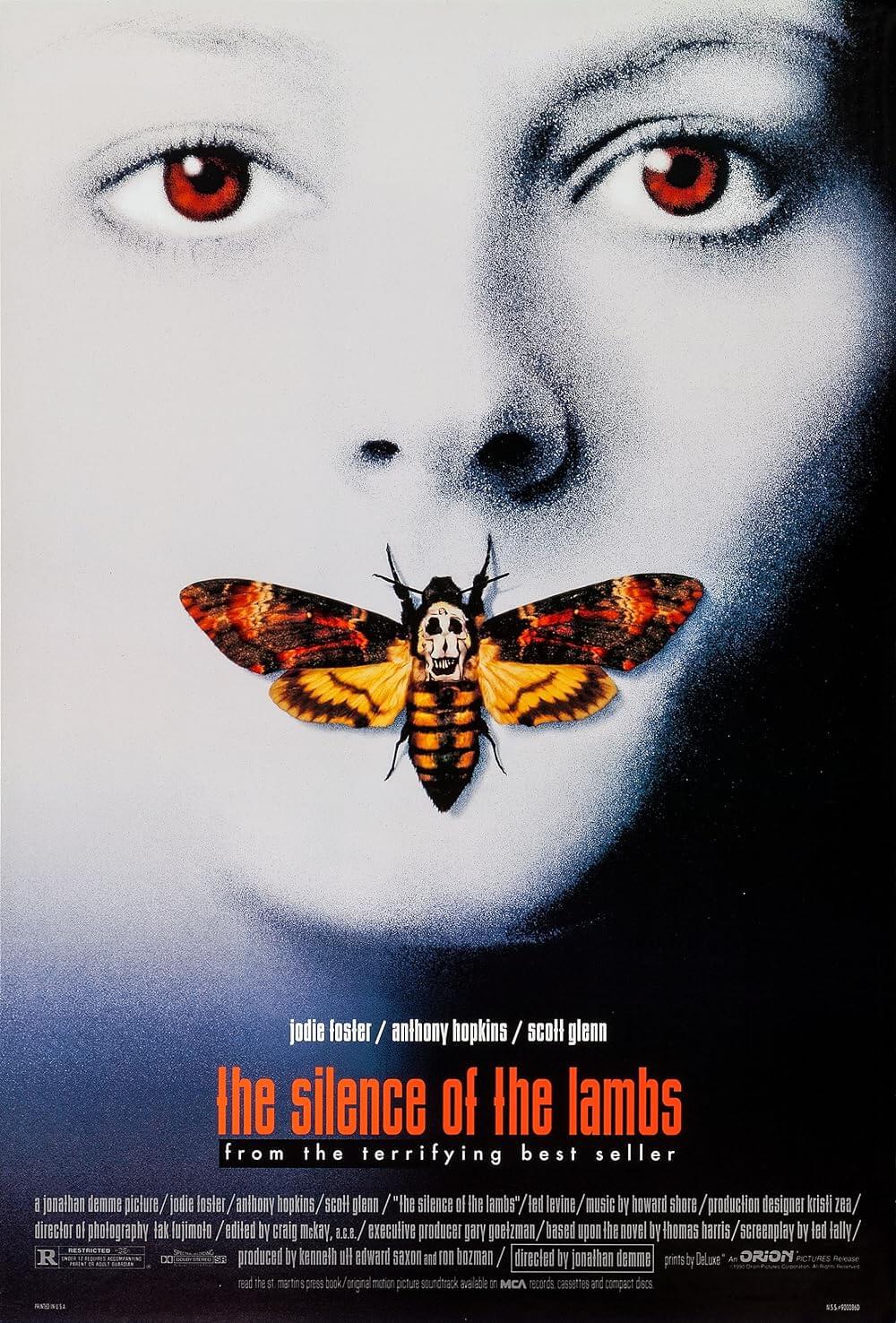

But Bigelow’s intellectual objective reduces Turner to a gender studies prompt rather than a compelling character whose choices drive the story. As mentioned, Turner makes choices that will aggravate most viewers, if not cause hands to be thrown up in frustration. Moreover, other examples of female authority figures battling against a patriarchal system and gendered power dynamics prove far superior. Consider The Silence of the Lambs (1992) and how, similar to Turner, Clarice Starling fails an early training exercise by not checking a corner. But director Jonathan Demme allows his protagonist enough intelligence to overcome her male counterparts in the narrative with more than brute force—notably, without defining Starling by her sexuality in a romantic sex scene or as a rape victim. This is not to suggest that Bigelow shouldn’t explore Turner’s sexuality. Rather, Blue Steel bears sloppy screenwriting in its procession of conveniences and improbabilities that integrate each aspect of Turner’s life in what seems like her first week on the job—she graduates, kills a man, gets suspended, becomes the target of a serial killer, earns a promotion, loses her best friend, arrests her father, falls for her partner, survives a rape, and kills the bad guy in just 104 minutes. Perhaps such plot mechanics are conditional to the genre or Bigelow’s heightened style of filmmaking, but they border on the comically over-the-top.

But Bigelow’s intellectual objective reduces Turner to a gender studies prompt rather than a compelling character whose choices drive the story. As mentioned, Turner makes choices that will aggravate most viewers, if not cause hands to be thrown up in frustration. Moreover, other examples of female authority figures battling against a patriarchal system and gendered power dynamics prove far superior. Consider The Silence of the Lambs (1992) and how, similar to Turner, Clarice Starling fails an early training exercise by not checking a corner. But director Jonathan Demme allows his protagonist enough intelligence to overcome her male counterparts in the narrative with more than brute force—notably, without defining Starling by her sexuality in a romantic sex scene or as a rape victim. This is not to suggest that Bigelow shouldn’t explore Turner’s sexuality. Rather, Blue Steel bears sloppy screenwriting in its procession of conveniences and improbabilities that integrate each aspect of Turner’s life in what seems like her first week on the job—she graduates, kills a man, gets suspended, becomes the target of a serial killer, earns a promotion, loses her best friend, arrests her father, falls for her partner, survives a rape, and kills the bad guy in just 104 minutes. Perhaps such plot mechanics are conditional to the genre or Bigelow’s heightened style of filmmaking, but they border on the comically over-the-top.

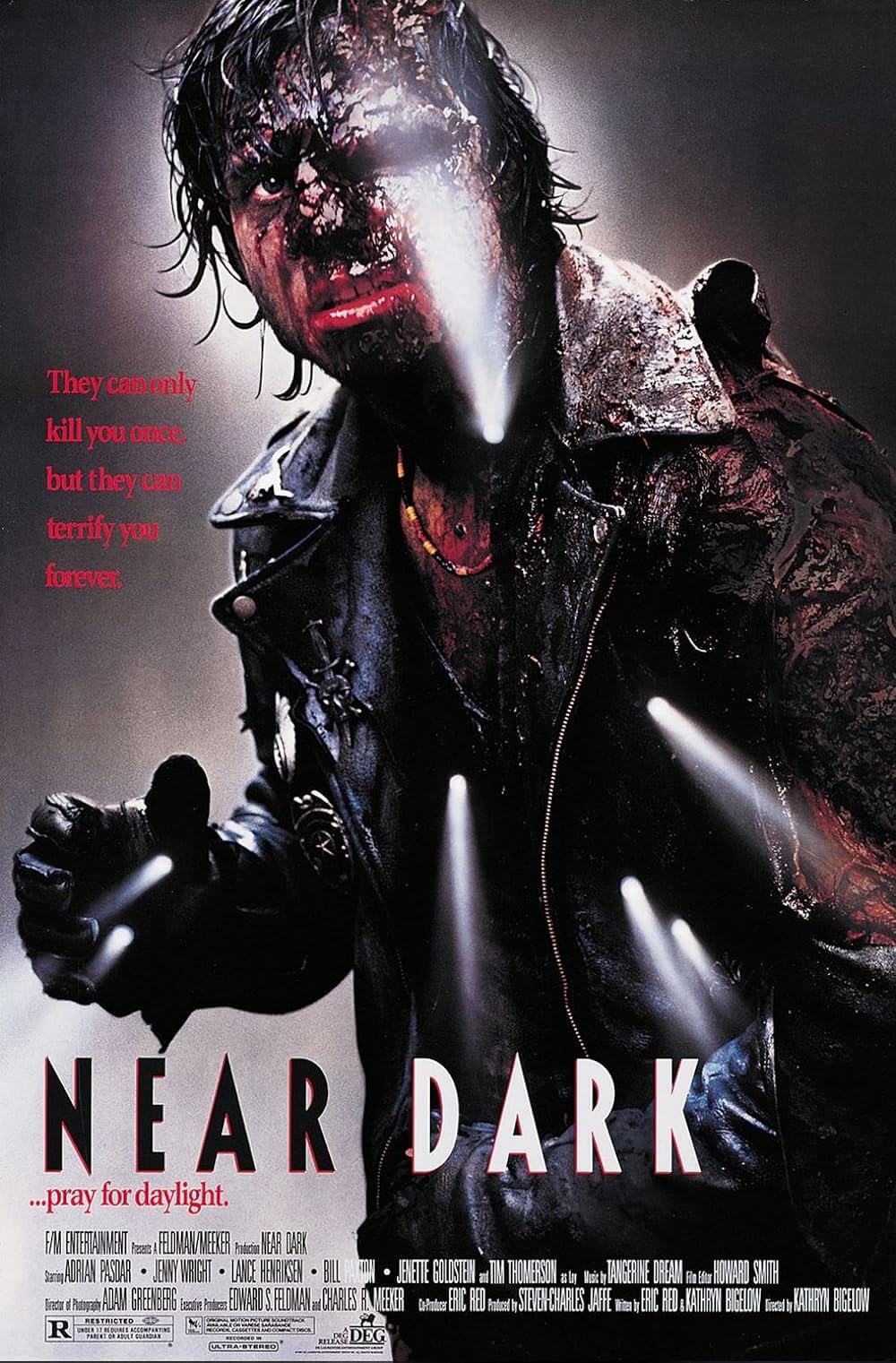

Unquestionably, Blue Steel bears many characteristics associated with Bigelow’s brand of cinema. Like her previous film, the superb Near Dark (1987), which blends noirish visuals and Western iconography with postmodern vampires, the director rethinks established genres with an eye toward masculine archetypes and feminist critique. Her interest in themes of gender, violence, and rape would again emerge in her masterful Strange Days (1995)—another film whose villain, like Eugene, wants his victims to witness their own pain and demise from an outside perspective. Additionally, Bigelow presents Turner as an alternative to standard masculine power, just as the opening title sequence reflects the handgun’s intersexual construction of both external and internal components. But the hero isn’t merely a woman in a man’s role, such as Sigourney Weaver’s so-called “Rambolina” as Ellen Ripley in the Alien franchise. Turner becomes more than the “phallic feminine” in Bigelow’s hands, albeit in a way that complicates her character in unsatisfying ways from a dramatic perspective.

In a sense, Turner becomes Bigelow’s onscreen counterpart—a figure who uses traditionally masculine methods to explore whether those characteristics are innately masculine, socially constructed as such, or some other complicated mixture. Bigelow would go on to make relatively straightforward masculine films, such as Point Break (1991). Still, her best work combines masculine and feminine elements in an ongoing conversation about power and gender in cinema. Blue Steel poses questions about whether female agency can exist beyond the confinements of patriarchal power violence and sexual violence, therefore acknowledging how the issue remains invasive and frightening to consider, given the events around Turner. But the film’s methods, however intriguing as a source of intellectualized discussion, fail to satisfy basic genre necessities—such as characters who behave in emotionally convincing ways instead of ways that feel compelled by screenwriters with more pressing matters on their minds. If Blue Steel succeeds in supplying a text for gender studies courses, it falls short of the basic requirements of a thriller.

(Note: This review was originally suggested on and posted to Patreon on May 25, 2022.)

Bibliography

Kaplan, Cora. “Dirty Harriet/Blue Steel: Feminist Theory Goes to Hollywood.” Discourse, vol. 16, no. 1, 1993, pp. 50–70. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41389301. Accessed 22 May 2022.

Powell, Anna. “Blood on the Borders: Near Dark and Blue Steel,” Screen, 35, 2 (summer), 1994, pp. 136-156.

Schwendenwien, Jude. “Review: Blue Steel.” Cinéaste, vol. 18, no. 1, 1990, pp. 51–21. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41687033. Accessed 22 May 2022.

Self, Robert T. “Redressing the Law in Kathryn Bigelow’s Blue Steel.” Journal of Film and Video, vol. 46, no. 2, 1994, pp. 31–43. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20688036. Accessed 22 May 2022.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review