Blue Jean

By Brian Eggert |

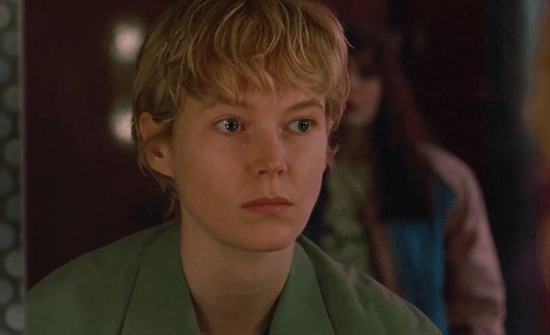

Tender and poignant, Blue Jean places a lesbian relationship at the center of a prescient drama that, though set in 1988, feels like a mirror of today. The debut feature from British writer-director Georgia Oakley follows Jean, played with bracing inner conflict by Rosy McEwen, a Newcastle gym teacher who hides her sexuality depending on the situation. In one of Jean’s lessons, she coaches her class of teenage girls about “fight-or-flight” in basketball, an apt parallel for how Jean deals with her sexuality in a culture that has stigmatized her community. For example, although she regularly goes out with her fellow lesbian friends to a queer bar, she feels pressure to deny that side of her identity in family or work situations, fearing awkward social interactions or even career repercussions. She hasn’t entirely committed herself to being out and embracing the local LGBTQ+ community, creating fissures in the personal and professional sides of her life. Beautifully acted and shot, Blue Jean finds its indecisive protagonist caught between hiding but perpetuating a prejudicial system or risking her livelihood. What makes the film feel so urgent is that Jean’s situation is playing out in current conversations, both on individual and corporate levels, making the film seem of this moment.

Oakley sets her feature just after Margaret Thatcher’s conservative government passes Clause 28, a limitation on the “promotion of homosexuality” by local authorities. The legislation deemed same-sex partners a “pretended family relationship” and sought to keep any discussion of LGBTQ+ issues out of the public discourse, especially in schools. The 25-year-old homophobic legislation, dissolved in 2003, gained steam in response to the AIDS epidemic. It also can’t help but echo contemporary anti-queer and transphobic rhetoric in America, which has led to book bannings, anti-trans legislation, Florida governor Ron DeSantis’ so-called Don’t Say Gay bill, and the current paranoid oversight of classroom discussions. Although the language of Clause 28 and today’s counterparts claim they’re designed to protect children, they serve to advance heteronormative social learning—a kind of preemptive conversion therapy. But many children already identify with and experience such feelings, and suppressing any discussion of them reinforces dangerous preconceptions that LGBTQ+ identities are somehow abnormal. This leads to discrimination, prejudice, and on a personal level, crisis.

The protagonist in Blue Jean grapples with the outcomes of Clause 28. A recent divorcée who realized she’s a lesbian, Jean responds to the legislation by establishing clear boundaries in her life. Although she has carved out a new identity, complete with a short, bleach-blonde hairstyle, she keeps her nightlife with her girlfriend, Viv (Kerrie Hayes), a secret from her workplace. Her sister Sasha (Aoife Kennan) knows and superficially accepts it, but Sasha doesn’t want Jean’s nephew Sam to know about her lesbianism. By contrast, Viv doesn’t see the point in hiding her identity; with her buzzed head, punk t-shirts, and tattoos, she embodies a certain defiant ’80s lesbian stereotype. Having leaped out of the closet, Viv doesn’t want to be drawn back in, making Jean’s refusal to take calls at work and description of Viv as a “friend” hurtful. Jean remains fraught, losing sleep over her situation and self-denial. With Jean at odds with herself, McEwen contains a flurry of intricate emotions within restrained expressions. By contrast, Hayes and the other women in Jean and Viv’s friend group (Stacy Abalogun, Izzy Neish, Aoife Kennan) lend freedom and openness to their performances.

Jean’s suppression of herself becomes even more troublesome with the arrival of a new student in her class, Lois (Lucy Halliday). The 15-year-old appears shy in gym class, where her classmates, led by mean girl Siobhan (Lydia Page), bully her, correctly guessing that she’s a lesbian. But Lois is assured enough to sneak into Jean’s queer bar, and Halliday’s performance is as sensitive and fearless as her character. Still, Jean recognizes the danger of the underage teen seeing her. And even after they know each other’s secret, she refuses to stand up for Lois when it matters. Oakley’s screenplay carefully maneuvers the moral traps, where Jean might sacrifice her career if she opens up, but she might be unable to live with herself if she doesn’t. Jean’s behavior, by extension, discourages Lois from accepting who she is, and in turn, she fails Lois the way so many people failed her. It’s a crushing realization that inspires Jean to worry less about the institutions that demonize her and more about the community that supports her.

Jean’s suppression of herself becomes even more troublesome with the arrival of a new student in her class, Lois (Lucy Halliday). The 15-year-old appears shy in gym class, where her classmates, led by mean girl Siobhan (Lydia Page), bully her, correctly guessing that she’s a lesbian. But Lois is assured enough to sneak into Jean’s queer bar, and Halliday’s performance is as sensitive and fearless as her character. Still, Jean recognizes the danger of the underage teen seeing her. And even after they know each other’s secret, she refuses to stand up for Lois when it matters. Oakley’s screenplay carefully maneuvers the moral traps, where Jean might sacrifice her career if she opens up, but she might be unable to live with herself if she doesn’t. Jean’s behavior, by extension, discourages Lois from accepting who she is, and in turn, she fails Lois the way so many people failed her. It’s a crushing realization that inspires Jean to worry less about the institutions that demonize her and more about the community that supports her.

Blue Jean fits squarely into the subgenre of lesbian period romances in recent years, including Todd Hayne’s Carol (2015), Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019), Francis Lee’s Ammonite (2020), and Mona Fastvold’s The World to Come (2020). The film ranks in the middle of these examples, boasting terrific performances and a thoughtfully considered formal execution. Cinematographer Victor Seguin shoots in soft, muted colors for an earthy aesthetic that resists the grit and grime of most British social dramas—a mood accented by Chris Roe’s lyrical, tonal score. But Oakley also inserts a few symbolic moments that feel heavy-handed but no less deeply felt for their obviousness. For instance, Jean keeps a goldfish, which her white cat watches from outside the tank. Doubtless, Jean, too, feels confined inside a glass box with a threat looming outside, able to see beyond her socially prescribed walls but unable to escape. In another example, Jean sees two horses running free in the distance, representing an evident desire to live free and unimpeded with Viv.

Oakley employs other poetic flourishes with more subtlety. A recurring theme in Blue Jean involves the television show Blind Date, a nightly program that reinforces binary gender norms. It’s a background detail that might go unnoticed, but when people are taught to think only in those terms, anything outside of it seems strange and wrong. When people learn that, in the real world, not everyone can be shuffled into one of two categories, they will see similarities instead of differences. With that in mind, Blue Jean becomes a thoughtful study of how some ideas are transmitted, and others are withheld, and how that can affect people. Oakley’s themes of education, community, and social pressure may have far-reaching implications; however, Blue Jean never feels didactic or sermonizing about these issues. The specificity of the historical setting and her screenplay’s sharp attention to Jean’s inner life offer a powerful, universal, and timely film despite its focused character study. Oakley’s attention to McEwen’s pensive and wounded face draws the viewer into a heartrending story—even hopeful, though the conversation continues over thirty years later.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review