Reader's Choice

Blonde

By Brian Eggert |

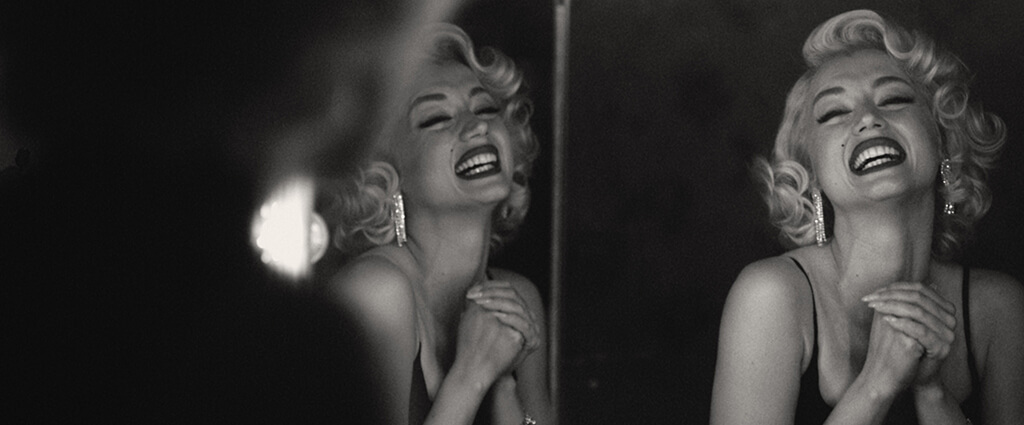

Director Andrew Dominik has made films about a notorious Australian criminal (Chopper, 2000); one of the American West’s most famous outlaws (The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, 2007); a group of vicious mobsters, hitmen, and scuzzy lowlife criminals (Killing Them Softly, 2012); and his next film is about Navy SEALs. Given that his work centers almost exclusively on violent men, it’s curious that he has made Blonde, a portrait of Marilyn Monroe’s objectification by the late Hollywood studio system and, by extension, American culture. Monroe was one of the twentieth century’s most recognizable icons, but she lived a hard life as an obscure object of desire. Dominik’s bleak look at Monroe shows the performer used, abused, chewed up, and spit out by the men in her life. In a way, it continues his career-long preoccupation, albeit by focusing on the receiver of male violence. Ana de Armas gives a convincing and sympathetic portrayal of Monroe, but the two-hour-and-forty-minute Netflix production ultimately makes the same points experimental filmmaker Bruce Conner made in his 14-minute short film “Marilyn Times Five” in 1973—that Monroe was a victim of voyeurism, and that the fetishization of her image only furthers the tragic legacy of her story.

Of course, Marilyn Monroe was more than what the men in her life made of her and more than a tragic figure, which is part of her story often overlooked by filmmakers—see the HBO original movie Norma Jean & Marilyn (1996) or Simon Curtis’ My Week with Marilyn (2011). It’s easier and more dramatically potent to consider her juxtaposition of sadness and beauty in a self-serious biography. Blonde continues that unfortunate tradition, offering the most gorgeously photographed and technically sumptuous contribution to the many films about her life. But its assessment of Monroe as a human being remains two-dimensional at best, consisting of punishing scenes of sexual abuse, degradation, and drug addiction, framed within her bifurcated identities: the real person of Norma Jean and the façade of Marilyn Monroe. The film, rated NC-17—not because it’s tantalizing but because it forces the viewer into traumatizing situations, sometimes involving rape—has been accused by detractors of exploiting Monroe’s trauma for art’s sake. The number of hot takes on Blonde has become staggering, and someone should use them to write a Master’s thesis about media interpretation, journalistic reactionism, and performative outrage.

Some of the discourse surrounding Blonde as of this writing—in various think pieces, scathing reviews, and in-defense-of responses—has noted Dominik’s loose treatment of the facts. His screenplay draws from Joyce Carol Oates’ openly fictionalized 2000 book of the same name. Even so, many have decried Dominik’s lack of biographical dimension and questioned his use of artistic liberties, despite Dominik and Oates admitting their artworks are bio-fiction. After all, filmmakers have never stuck to the facts about real-life figures—movie biopics have exercised poetic license for well over a century, even though it’s often an issue for many critics, fans, and history buffs. Biopics deploy composite characters, compressed timelines, fictionalized scenes for dramatic effect, and glossed-over events to simplify their subject and offer a framework through which the audience can understand them. Most feature a disclaimer, warning that the story is an artistic interpretation, which means it’s about as true to life as a painter’s oil on canvas portrait. So perhaps it’s best to avoid weighing biopics and historical films according to their factual substance. Cinema is driven by emotional and artistic outcomes, not its allegiance to historical detail. Still, the film’s most vocal critics want to see everything about Monroe’s life that Dominik overlooked.

Some of the discourse surrounding Blonde as of this writing—in various think pieces, scathing reviews, and in-defense-of responses—has noted Dominik’s loose treatment of the facts. His screenplay draws from Joyce Carol Oates’ openly fictionalized 2000 book of the same name. Even so, many have decried Dominik’s lack of biographical dimension and questioned his use of artistic liberties, despite Dominik and Oates admitting their artworks are bio-fiction. After all, filmmakers have never stuck to the facts about real-life figures—movie biopics have exercised poetic license for well over a century, even though it’s often an issue for many critics, fans, and history buffs. Biopics deploy composite characters, compressed timelines, fictionalized scenes for dramatic effect, and glossed-over events to simplify their subject and offer a framework through which the audience can understand them. Most feature a disclaimer, warning that the story is an artistic interpretation, which means it’s about as true to life as a painter’s oil on canvas portrait. So perhaps it’s best to avoid weighing biopics and historical films according to their factual substance. Cinema is driven by emotional and artistic outcomes, not its allegiance to historical detail. Still, the film’s most vocal critics want to see everything about Monroe’s life that Dominik overlooked.

Dominik’s approach has been called “wrong” many times. But the problem with Blonde isn’t a moral issue so much as Dominik’s choice to interpret Monroe’s life as a series of grueling episodes. They involve her unhappy childhood, cruel men, substance abuse, forced abortion, sexual assaults, and demeaning treatment by people who underestimate her intelligence. The problem is that Blonde offers nothing new and raises no questions about the Monroe myth that has been perpetuated since her death at 36. Instead, the director portrays her life as drifting from one trauma to the next, with few signs of happiness or inner life beyond her tragic conformity into the “Marilyn Monroe” mold. Every man in her life mistreats her; she receives no end of ogling and abuse. And while there’s no doubt truth in this ruined portrait of a pin-up-girl-turned-movie-star—an icon who has been reduced to a familiar set of attributes by everyone from Andy Warhol to Wayne Campbell—it’s a narrow perspective that doesn’t question the myths told about Monroe for half a century. There’s nothing “wrong” with Dominik’s approach in that an artist should interpret their subject according to what inspires them. But his course is uncurious and rehashes old ideas in a film that takes a long time to make the same point that Conner and others have since made.

The first shot is a dreamy black-and-white sequence of Monroe filming the famous scene from Billy Wilder’s The Seven Year Itch. Even if you haven’t seen this 1955 film—and I don’t recommend you do—you know the movie moment: A gust of wind blows up Monroe’s white dress from a subway grate, exposing her legs, and she purrs, “Isn’t it delicious?!” In that film, she plays the neighbor of a married man who fantasizes about her, so it’s an apt place for Dominik to start with Monroe—a movie character who typifies a particular erotic ideal in a scene replicated countless times in parodies and references. But the scene was filmed with a crew leering at her from behind the camera, turning her performance into a show not only for the eventual moviegoer but a crude violation by her fellow filmworkers. Dominik’s perspective on the moment isn’t any better; he spies her from behind, rendering her faceless and exposed in an obvious visual reduction of her image from human to object. Similar examples include one of Monroe’s nude calendars displayed backstage on a movie set or her fan(atics) mutating before our eyes as they rush to catch a glimpse of her. Blonde constantly reminds its audience of how Monroe was objectified and consumed by those around her, even while Dominik’s screenplay does the same by recreating such fantasy moments and buying into her desirous image.

Every mechanism in Dominik’s cinematic toolkit portrays Monroe as someone robbed of subjectivity by dehumanizing voyeurism. The chilling score by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis gives the proceedings an almost horror movie atmosphere. The frequent use of flashbulbs popping—a jarring tactic seen in Martin Scorsese’s The King of Comedy (1985), another film about celebrity and desire—suggests the jarring effect of celebrity life. Chayse Irvin’s incredible cinematography alternates between black-and-white and color, boxy aspect ratios to wide, but not always with clear reasoning for the transitions. Regardless, the images are beautifully captured; even some of the most disturbing incidents have a stunning visual artfulness, such as an abortion scene that descends into a fiery, hallucinatory nightmare—all of it marvelously photographed. Blonde is a film that continuously juxtaposes gorgeous filmmaking with unforgiving situations. Elsewhere, Dominik uses expert CGI to insert de Armas’ face into scenes from Monroe’s most iconic films, such as All About Eve (1950) and others. Her pinup calendars, magazine covers, and print ads come alive onscreen, recalling a technique used in Mary Harron’s superior The Notorious Betty Page (2005). And in perhaps the film’s silliest and most absurd and baffling flourish, the virtual camera takes us inside Monroe’s vagina to visit her second unborn child, which beckons not to be aborted: “You won’t do the same thing to me, will you?”

Every mechanism in Dominik’s cinematic toolkit portrays Monroe as someone robbed of subjectivity by dehumanizing voyeurism. The chilling score by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis gives the proceedings an almost horror movie atmosphere. The frequent use of flashbulbs popping—a jarring tactic seen in Martin Scorsese’s The King of Comedy (1985), another film about celebrity and desire—suggests the jarring effect of celebrity life. Chayse Irvin’s incredible cinematography alternates between black-and-white and color, boxy aspect ratios to wide, but not always with clear reasoning for the transitions. Regardless, the images are beautifully captured; even some of the most disturbing incidents have a stunning visual artfulness, such as an abortion scene that descends into a fiery, hallucinatory nightmare—all of it marvelously photographed. Blonde is a film that continuously juxtaposes gorgeous filmmaking with unforgiving situations. Elsewhere, Dominik uses expert CGI to insert de Armas’ face into scenes from Monroe’s most iconic films, such as All About Eve (1950) and others. Her pinup calendars, magazine covers, and print ads come alive onscreen, recalling a technique used in Mary Harron’s superior The Notorious Betty Page (2005). And in perhaps the film’s silliest and most absurd and baffling flourish, the virtual camera takes us inside Monroe’s vagina to visit her second unborn child, which beckons not to be aborted: “You won’t do the same thing to me, will you?”

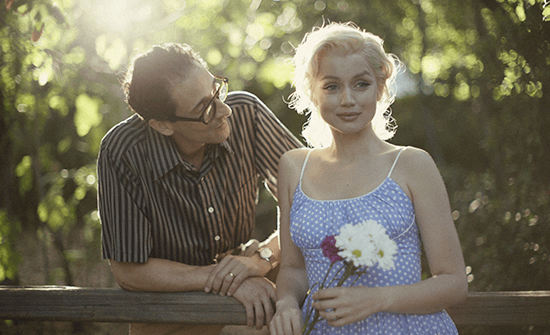

Besides talking fetuses and more than one journey inside Monroe’s vagina, Dominik’s screenplay is full of bizarre choices that alternately frustrate and alienate the viewer, usually while presenting something aesthetically compelling onscreen. Blonde’s greatest trick is how someone as distinctive as de Armas disappears into her role, capturing Monroe’s appearance and voice (with only occasional hints of the actor’s Cuban accent) to impressive effect. It’s probably de Armas’ most challenging and substantive role yet, in that she’s required to portray someone usually in tears, reliving past trauma, enduring fresh anguish, and having mostly demeaning sex. Whether replicating a moment from film history or occupying Monroe’s beleaguered state, de Armas renders the emotion convincingly. What she doesn’t convey through her performance, she whispers in almost Malickian narration or remembers in one of Blonde’s many flashbacks. Along the way, familiar faces play important figures from Monroe’s life: Bobby Cannavale as Joe DiMaggio and Adrien Brody as Arthur Miller, for instance. They appear in shots of the film that recreate memorable Monroe photographs captured during photo shoots, which epitomizes Dominik’s approach throughout—an awkward intermingling of Marilyn Monroe’s output with her life in a manner that suggests Dominik is more interested in surfaces.

Fortunately, the sheer formal splendor, often horrible in context, and de Armas’ screen presence, which contains hints of something deeper, keep the viewer rapt in the film. Dominik has unquestionably delivered a work of some technical and visual exquisiteness. However, the endurance test quality of Blonde over its procession of miserable episodes recalls the thankless and historically questionable quality of 2020’s The Painted Bird—another long and evocatively filmed slog, set in Eastern Europe during World War II, with no interest in exploring its protagonist’s mind. For all of Dominik’s attempts to empathize with Monroe and condemn the voyeuristic mistreatment that turned her into a victim, Blonde rarely offers a dimensional character who counteracts her dehumanization. Dominik shows her so beaten down and subjugated that there’s nothing left, and to be sure, that’s his intention—to rub America and Hollywood’s nose in it and say, “Look what you did.” But in taking this approach, the director reinforces the power of Monroe’s limiting iconography and objectifies her further, only not in service of a sexual fantasy but as a portrait of an endless sufferer. Both takes are reductive.

(Note: This review was originally suggested on and posted to Patreon on October 6, 2022.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review