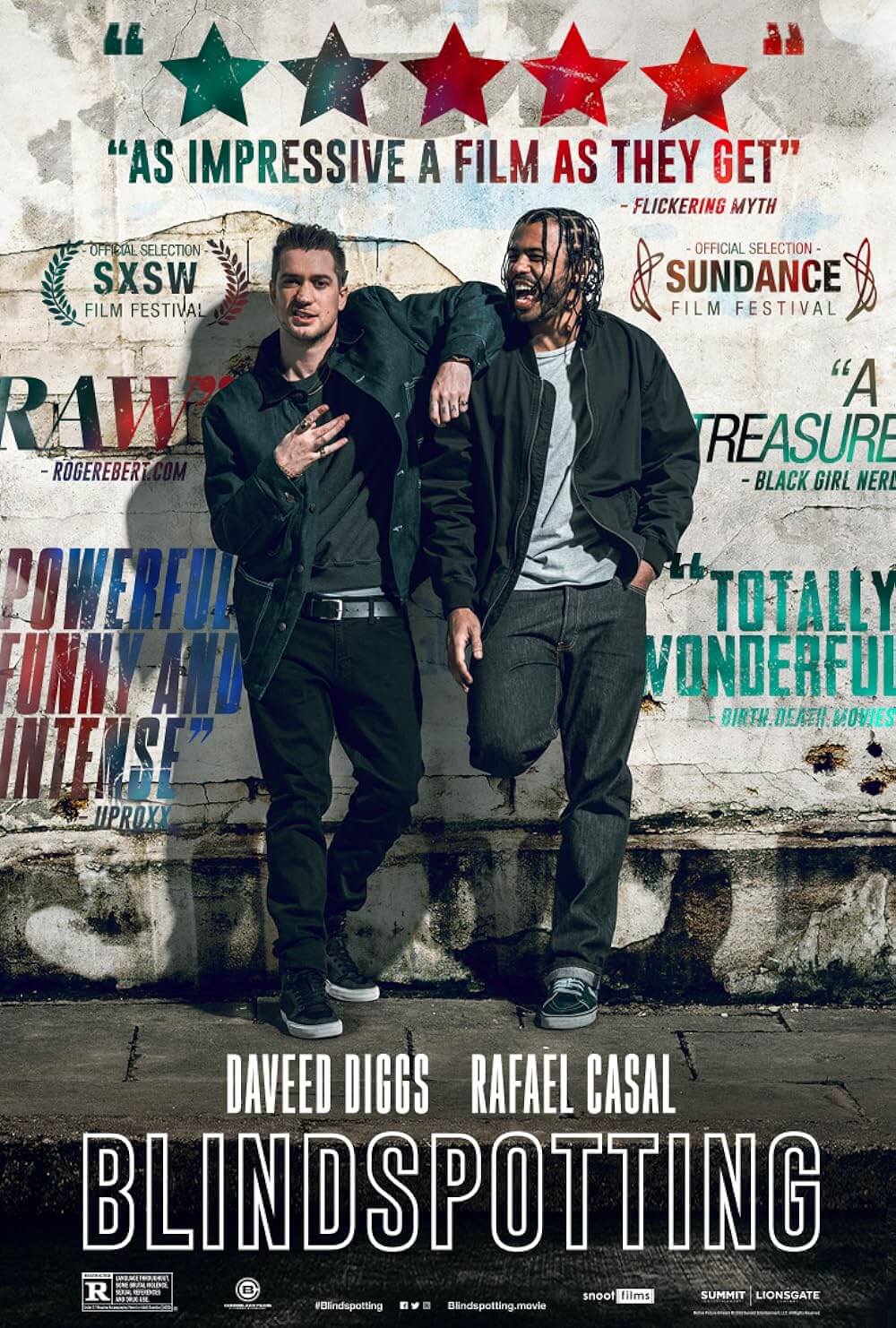

Blindspotting

By Brian Eggert |

When Danish phenomenologist Edgar Rubin conceived of “Rubin’s vase,” he imagined an optical illusion that reveals how the human mind instinctively chooses to see one perspective over another. His illusion is a black and white image, in the center of which the positive space resembles a vase, while the surrounding negative space appears as two faces looking at one another. Rubin’s theory proved that, when confronted with such visual duality, the human brain assigns predominance to the first of the two images it recognizes, while the second image recedes. If the brain sees the white vase at first, it must work harder to see the Black faces. This motif subsists at the center Blindspotting, whose title references the practice of looking outside of what you intuitively perceive, beyond your ingrained perspective, prejudices, and stereotypes. Written by and starring the Tony Award-winner Daveed Diggs and his creative partner Rafael Casal, the film explores issues of gentrification and the shifting tides of Oakland, California—from a city defined by its African American culture to a recent insurgence of white hipsters after the tech boom. But it also has much to say about the socioeconomic and class divide among Oakland’s population, as well as the shattered relationship between police and people of color. It’s a film that asks a lot of questions but provides no answers; however, it opens up an essential dialogue for our times.

A timely powder-keg-of-a-film, Blindspotting shares much in common with Spike Lee’s seminal Do the Right Thing (1989), in that its race and class tensions build to a decisive, explosive moment. Set in Diggs’ hometown of Oakland, the story follows Collin (the biracial Diggs), an ex-con with three days left of his parole. Collin has the support of his lifelong compadre, Miles (the white-Latino Casal), but he must examine whether their friendship outweighs Miles’ reckless behavior that could jeopardize his freedom. As the pressure mounts, Collin confronts the pretenses of his identity to move beyond that which he thinks holds him back. Additionally, though Blindspotting addresses relevant issues of the day and feels like a realistic depiction of its themes, like Lee’s film it takes place in a cinematic world that exists just beside our own, where dramatic formal touches, nightmarish dream sequences, and playful edits heighten reality. Director Carlos López Estrada, making his feature-length debut, makes his film a dynamic viewing experience that transitions from laughter to terrifying authenticity to angry tears in an instant—at times with the visual ornamentation of a music video.

The film’s fluidity and rhythms of tone have much in common with a musical, which makes sense given the roots of the talent involved. In recent years, Diggs earned acclaim for his roles as Thomas Jefferson and Marquis de Lafayette in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s hip-hop Broadway musical, Hamilton. Long before that, he attended the same high school in Casal’s hometown of Berkeley, just north of Oakland. The two grew up together in an area often considered an epicenter for the foundation of blues and jazz, and while Casal became a spoken-word poet and YouTube sensation, Diggs earned a reputation as a gifted freestyle rapper. Over the years, Diggs and Casal worked with various artists on hip-hop projects, and Estrada directed many of their videos. The two collaborated on the script for Blindspotting, a project that initially started as a work of entirely spoken-word rhymes before gradually, through nearly a decade of drafts and revisions, it became a comparably straightforward film with segments of verse worked into the real-world setting.

The film’s fluidity and rhythms of tone have much in common with a musical, which makes sense given the roots of the talent involved. In recent years, Diggs earned acclaim for his roles as Thomas Jefferson and Marquis de Lafayette in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s hip-hop Broadway musical, Hamilton. Long before that, he attended the same high school in Casal’s hometown of Berkeley, just north of Oakland. The two grew up together in an area often considered an epicenter for the foundation of blues and jazz, and while Casal became a spoken-word poet and YouTube sensation, Diggs earned a reputation as a gifted freestyle rapper. Over the years, Diggs and Casal worked with various artists on hip-hop projects, and Estrada directed many of their videos. The two collaborated on the script for Blindspotting, a project that initially started as a work of entirely spoken-word rhymes before gradually, through nearly a decade of drafts and revisions, it became a comparably straightforward film with segments of verse worked into the real-world setting.

It wasn’t long after New Year’s Day in 2009, when a BART officer shot and killed the unarmed Oscar Grant, that Diggs and Casal sought to capture the fear and anger of the Oakland community through their proposed film. Although the script would not go before cameras for years, the eventual production premiered at the 2018 Sundance Film Festival to enthusiastic responses. Not long before Sundance, the project received a post-production grant from the Dolby Family Sound Fellowship, allowing Estrada, Diggs, and Casal the opportunity to saturate their soundtrack with well-known artists, including Clyde Carson, Tower of Power, and Fantastic Negrito. Diggs and Casal also lend their vocals to several original songs on the soundtrack, enhancing the quality of Blindspotting as a work of personal expression through film and music, with both non-diegetic and diegetic hip-hop. Robby Baumgartner—who’s worked on some prestigious Hollywood productions in the lighting department and made his feature-length debut as a cinematographer on Adam Wingard’s The Guest (2014)—works with Estrada and editor Gabriel Fleming to create energized visuals in a pace that moves with incredible momentum (a lot happens in the film’s 95 minutes).

Fortunately, Diggs and Casal never attempt to solve the problems of social injustice within their film, nor does their treatment settle on an emblematic plot or rage as a solution. Blindspotting is more thoughtful. The effects of the area’s social condition remain apparent in nearly every interaction in their community, where pamphlets designed for children offer instruction about how to speak to police without being shot. Collin’s three-day countdown until his freedom from probation, and the feeling that any misstep could land him back in jail, echoes the same sentiment for every person of color in his neighborhood who worries about the cops finding a reason. Collin’s jail time for a violent crime, which remains a mystery until its lively and saddening flashback reveal, haunts him and stands as a constant reminder that his responsible ex-turned-boss, Val (Janina Gavankar), won’t let him forget. His status as an ex-con becomes a painful symbol of his feeling of powerlessness when Collin drives home one night just before his curfew and, at a stoplight, he witnesses a white officer (Ethan Embry) shoot an unarmed Black man on the run—something that seems to happen in the real world every few weeks these days. He does and says nothing, fearing that his criminal history could be used against him. Miles, meanwhile, grapples with his own issues of identity; he rejects the changes to Oakland and prefers an outdated, irresponsible, and decidedly more aggressive version of his city.

Despite such heavy situations, Blindspotting deepens the relationship between Collin and Miles through a humorous portrait of their childish adult friendship. A scene where Miles hocks several hand-me-down hair curlers and straighteners to a local salon owner (Tisha Campbell-Martin), using his charismatic spoken-word skills, is riotous. But the script often turns the lived-in bromance scenes between Collin and Miles into dangerous moments later in the film. In an early scene, Miles buys a handgun right in front of Collin, who urges his friend to put the gun away so he can claim “plausible deniability.” The weapon is almost forgotten until Miles’ young son (Ziggy Baitinger), perpetually roughhousing like his father, finds it, and his wife Ashley (Jasmine Cephas Jones) freezes in terror. The film disarms through a steady supply of humor scene after scene, yet it never allows the characters or the audience to settle, which keeps us on edge.

This is the genius of Blindspotting, as it replicates the unsettled feeling that Collin lives with, while Miles can too easily forget or ignore his friend’s everyday experience. Their acclimatization to their surroundings accepts the inevitability of violence or persecution by the police, and thus demands that they are shaken out of their complacency to acknowledge how this is unacceptable. The threat of prison, gun violence, or police shootings remains a constant presence in their lives, to the extent that such events have been normalized, and in some cases romanticized, to frightening degrees. Recognizing that the way of life they’ve always known is not the only way becomes a vital lesson. And fortunately, the film never feels preachy or more significant than the microcosmic world of Collin’s neighborhood, making it perfectly suited to reach beyond the Oakland city limits. Estrada directs Diggs and Casal to give natural, human performances, accentuated with an exhibitive streak that makes the entire film into a work of cinematic performance art. With vivid filmmaking, outrage, poetics, humor, and a yearning for contemplation, Blindspotting asks for discourse about why things are the way they are, and how we can change them.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review