Blade Runner 2049

By Brian Eggert |

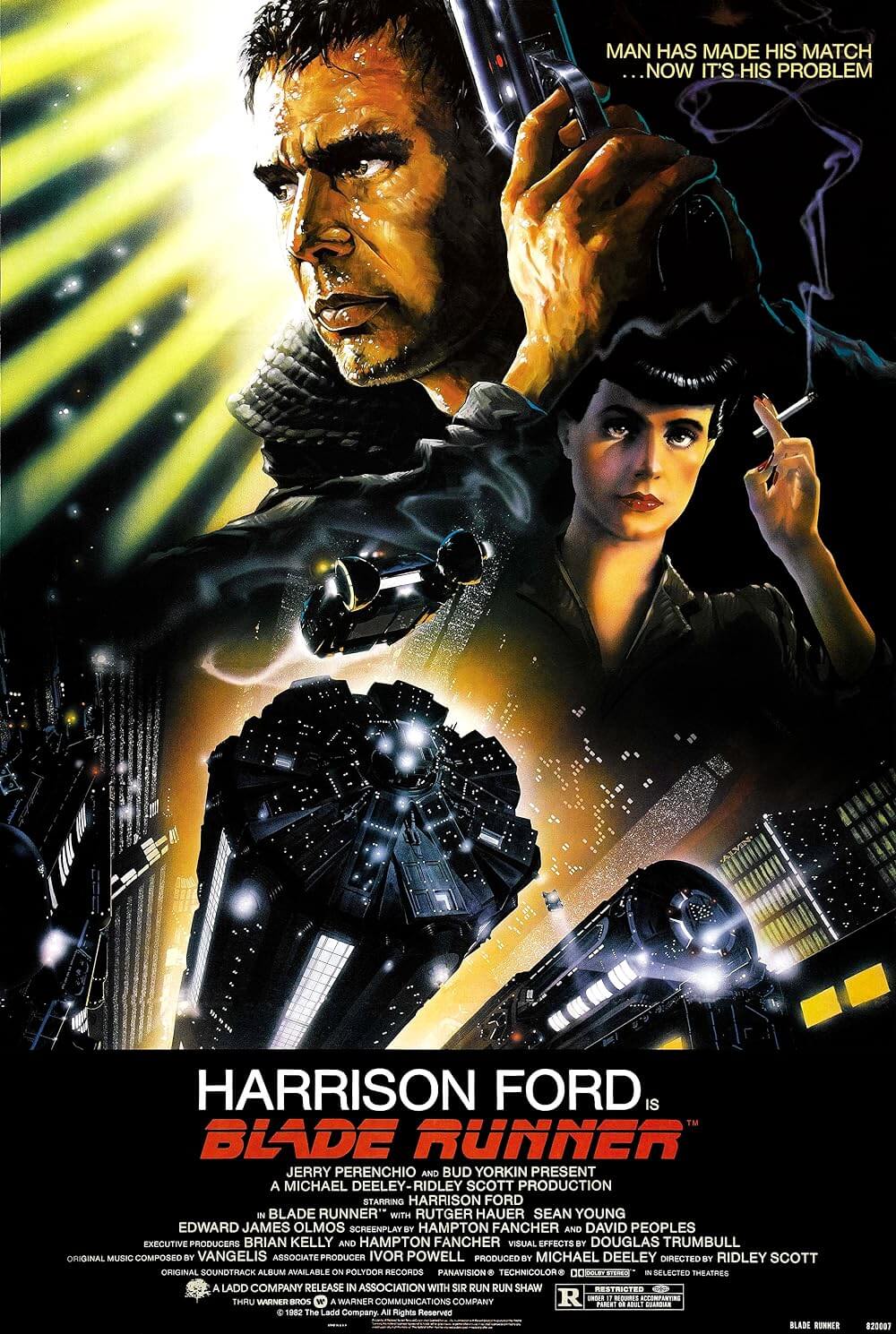

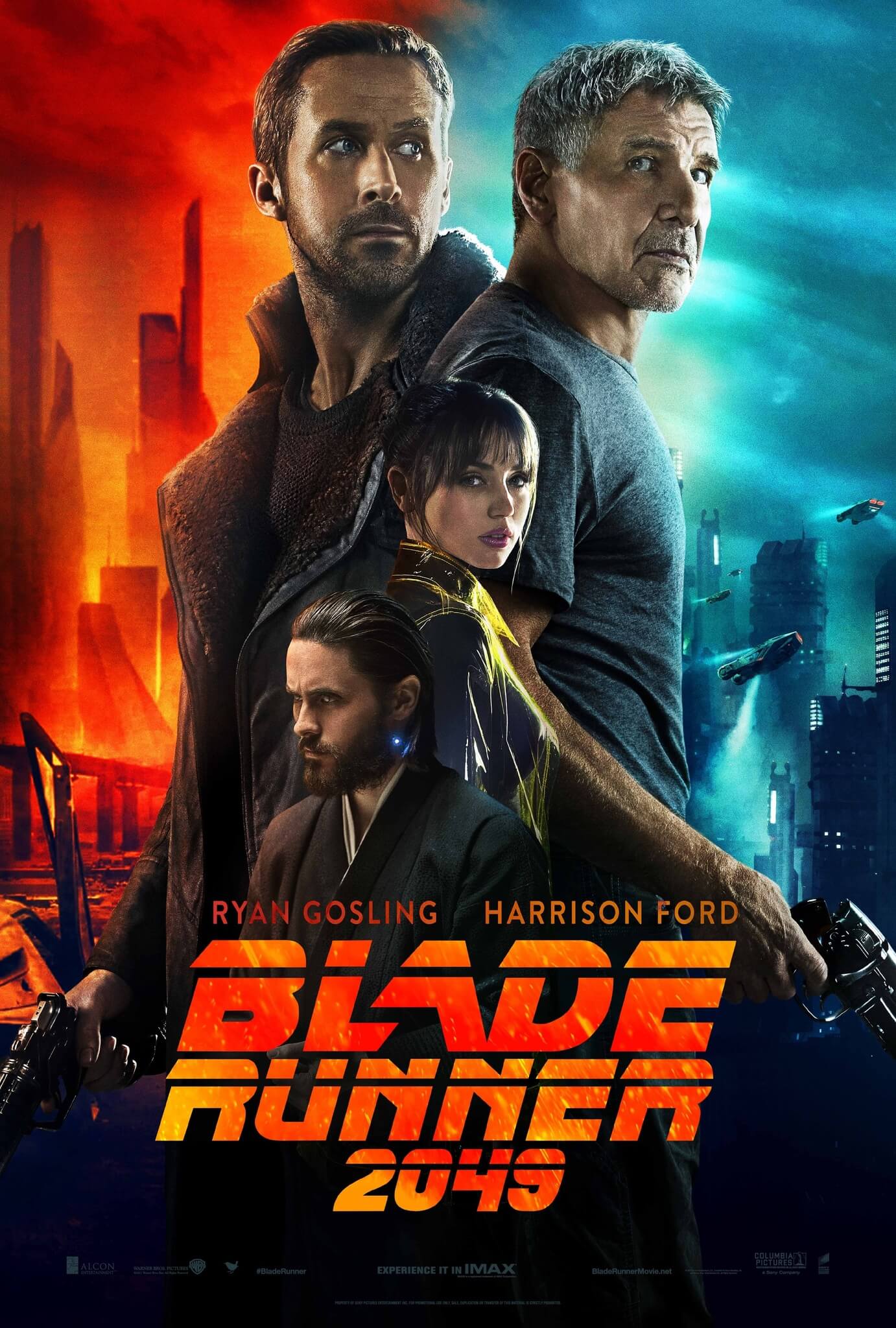

Los Angeles has not yet become the rainy dystopia of blazing spires, sparkling ziggurats, and off-world advertisements as shown in Ridley Scott’s visionary Blade Runner. Set in 2019, the film envisioned a tomorrow far removed from that of its 1982 release, and looking back, Scott’s masterwork remains futurist and postmodern with influences of German expressionism, film noir, and cyberpunk. The technology gap between the real world’s 1982 and the film’s 2019 was more extreme than the three decades between the original film and Denis Villeneuve’s sequel, Blade Runner 2049. The distant future still appears to be a sprawling megalopolis cluttered with stories-high video screens, flying cars, and persistent gloom, and the modest changes allow further exploration into the philosophical and existential questions that permeate this world. Philip K. Dick’s 1968 science-fiction novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? provided the springboard for Scott’s classic, and Villeneuve dives into the influential author’s preoccupations with identity, the illusory nature of reality, and the potential of artificial intelligence. Over a nearly three-hour runtime, Blade Runner 2049 maintains a deliberate, thoughtful pace that allows for entrenched contemplation, leaving the viewer enraptured by its incredible visuals, narrative puzzlework, and unexpected emotional substance.

In the world of 2049, humans rely on millions of genetically engineered androids, called replicants, to explore the outer reaches of space and find new worlds to inhabit. Though newer replicant models, Nexus-8 and above, have open-ended lifespans, they serve at the pleasure of their human counterparts as a servant class. Should a replicant act out or escape, authorities elicit the services of a blade runner, a sort of bounty hunter. Although there was some question about whether Harrison Ford’s blade runner, Rick Deckard, from the original film, was human or a replicant, there’s no uncertainty about officer “K” (Gosling), short for KD6.3-7, a replicant who hunts rogue androids for the LAPD. Gosling’s impenetrable, straight-faced restraint that carried his performance in Drive (2011) returns here, and the slightly asymmetrical placement of his eyes suggests a synthetic person with imperfections—some might call them glitches, others might call them signs of humanity. Checking in after an early mission, he’s subject to a rigorous “baseline” exam, a sort of Voight-Kampf test derived from Vladimir Nabokov’s 999-line poem Pale Fire. “Cells interlinked within cells,” a voice reads. “Cells,” Gosling’s character repeats, “interlinked,” and the words somehow place a burden on him.

Beneath those cold eyes, K longs to be a real boy. The shades of Pinocchio in Blade Runner 2049 aren’t the first time science-fiction has adopted imagery from Carlo Collodi’s storybook, either; A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001) also pulled from that well. Indeed, the screenplay by Hampton Fancher (co-writer of the original Blade Runner) and Michael Green bears resemblance to Steven Spielberg’s underappreciated 2001 release, at least in terms of the blurred lines between human and artificial life. The new owner of the replicant factory, the Tyrell Corporation, is a synthetic farmer named Niander Wallace (Jared Leto, behind grayed-out eyes and a hovering neuro-camera system). Wallace may deliver the film’s most stilted dialogue (Leto’s performance is the film’s major low point), but he openly admits that his slave-labor product allows humans to thrive on nine off-world colonies throughout the galaxy. He has helped foster a fascistic order that places humans on top of a social hierarchy and replicants in an inhuman labor class. Going further, the film has been coded, visually and thematically, with the colors of black and gold to echo the presence of bees in one scene, suggesting a parallel to the worker-replicants. The comparison recalls A.I.‘s robots called “Mecha,” who, in contrast to the human “Orga,” functioned as servants, often humiliated or even tortured for the spectacle of their human masters.

Beneath those cold eyes, K longs to be a real boy. The shades of Pinocchio in Blade Runner 2049 aren’t the first time science-fiction has adopted imagery from Carlo Collodi’s storybook, either; A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001) also pulled from that well. Indeed, the screenplay by Hampton Fancher (co-writer of the original Blade Runner) and Michael Green bears resemblance to Steven Spielberg’s underappreciated 2001 release, at least in terms of the blurred lines between human and artificial life. The new owner of the replicant factory, the Tyrell Corporation, is a synthetic farmer named Niander Wallace (Jared Leto, behind grayed-out eyes and a hovering neuro-camera system). Wallace may deliver the film’s most stilted dialogue (Leto’s performance is the film’s major low point), but he openly admits that his slave-labor product allows humans to thrive on nine off-world colonies throughout the galaxy. He has helped foster a fascistic order that places humans on top of a social hierarchy and replicants in an inhuman labor class. Going further, the film has been coded, visually and thematically, with the colors of black and gold to echo the presence of bees in one scene, suggesting a parallel to the worker-replicants. The comparison recalls A.I.‘s robots called “Mecha,” who, in contrast to the human “Orga,” functioned as servants, often humiliated or even tortured for the spectacle of their human masters.

K takes orders from his LAPD superior, the chilly Lt. Joshi (Robin Wright). In the film’s opening mission, he’s ordered to travel out over fields of solar panels to a grub farm on a desolate landscape, where he finds a replicant named Sapper Morton (Dave Bautista). After “retiring” his target (a clever word to override the cruelty of the act), K finds a box of bones from a once-pregnant replicant on Morton’s property. But the pregnancy leads to a dangerous question: If a replicant is born and not created, does it have a soul? Does it deserve rights? And if so, should any replicant be subjected to slavery? Lt. Joshi orders K to seek out and destroy the replicant child, now presumably an adult, in fear that the worker bees will lead an uprising if they learn to procreate. Meanwhile, Wallace wants the replicant offspring for himself—if only to produce his “angels” on a grander scale, which would allow more additions to his forced labor pool. So as K investigates a series of leads in his Philip Marlowe routine, Wallace’s loyal and savage replicant companion Luv (Sylvia Hoeks) watches, following K’s every move to locate the “miracle.”

But the narrative mystery driving Blade Runner 2049 provides a surface text for a more profound current in which K questions his identity as a slave. After a hard day at the office, he returns home through a crowd of human scum that slings “Fuck off, skin-job!” and other insults his way. In his small apartment, he’s welcomed home by his female hologram companion, Joi (Ana de Armas), another Tyrell invention. Imagine a visualized update of Scarlett Johansson’s OS from Her (2013), an artificial intelligence that transcends emotional boundaries, despite corporeal limitations. Although she’s a simulation attached to an overhead projector, K brings her an Emanator, which allows her to move about freely. He could almost kiss her, if she wasn’t semi-transparent. This leads to the film’s erotic, yet deeply moving scene wherein Joi tries to connect on an impossible physical level by hiring a prostitute (Mackenzie Davis) for a curious three-way. The sequence reveals a depth of melancholy and impossible longing between K and Joi—the burden of a servant class that remains superior in intelligence and physicality, yet unable to savor the connections afforded by humanity.

Villeneuve also manages to extract a vulnerable performance from Ford, his best in years, returning as Deckard at around two-thirds into the film. Holed-up in an abandoned casino and surrounded by bottles of whiskey, and a dog that may or may not be ersatz, Deckard enjoys his solitude before K interrupts it with his questions. Alas, not all of Blade Runner 2049 has such an affecting tone. Its sum is greater than its parts—which is to say, the film is a masterpiece but not without flaws. As mentioned, Leto’s performance seems operatic against the film’s otherwise restrained manner, and while the blame might be placed solely on the actor, his dialogue has been written with the flair of a Bond villain. Fortunately, his scenes are few. Similarly, the return of yet another beloved character from the original sparks memories of Peter Cushing and a young Carrie Fisher showing up in Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (2016), direct from the Uncanny Valley. But the very existence of an urgently engaging science-fiction tale, which spends its sprawling runtime asking introspective questions about identity and exploited classes instead of providing futurist action set-pieces, remains something truly exceptional. And this says nothing of its incredible beauty.

After previous collaborations with Villeneuve on Prisoners (2013) and Sicario (2015), longtime Coen brothers cinematographer Roger Deakins saturates Blade Runner 2049 with atmospherics and visual majesty that make comparable recent films, like Ghost in the Shell, look silly by comparison. Every shot is accented by rain, shadow, or smoke, and very often all three. Production designer Dennis Gassner creates elaborate sets, from a fried Las Vegas wasteland of gaudy fallen sculptures, which Deakins shoots in burnt oranges, to the oppressive dark and drenched city scenes illuminated by neon holograms and animated signage (Atari remains a fixture in this future). Although the umpteen multi-pass exposures on models and matte paintings used in the original have been replaced by CGI here, the effects look exceptional, without a false moment to interrupt our immersion into this world. Villeneuve and Deakins, supported by editor Joe Walker, deliver the film’s impressive eye-candy in long, pensive shots, often without dialogue or even music to disturb our gaze. Villeneuve’s use of silence is piercing, sometimes haunting. But Benjamin Wallfisch and Hans Zimmer’s score evokes Vangelis’ hypnotic music at times, while their synth-laden sounds also deepen into reverberating base notes that shake the foundation of a theater with a proper sound system.

Having recently screened Andrei Tarkovsky’s immersive 1979 odyssey Stalker, the unavoidable associations have left me convinced of Blade Runner 2049‘s arthouse sensibility—a quality worth celebrating, though it may be the film’s commercial undoing. So-called Slow Cinema has never been suited to mainstream audiences, not in its emergence with filmmakers such as Chantal Akerman, Michelangelo Antonioni, Ingmar Bergman, and Yasujiro Ozu, and certainly not among viewers of today’s hyperactive blockbusters. Warner Bros. made Blade Runner 2049 for $150 million, probably much more, but their losses will be short-term if the film resonates as Scott’s did—over several years, after repeated viewings, and some serious reflecting. That sort of reconsideration is necessary, as each long take that concentrates on K’s measured behavior presents the viewer with the gift of time: to think about the consequence of the scene, to absorb the artistry loaded into each shot, and to question the nature of these characters.

Having recently screened Andrei Tarkovsky’s immersive 1979 odyssey Stalker, the unavoidable associations have left me convinced of Blade Runner 2049‘s arthouse sensibility—a quality worth celebrating, though it may be the film’s commercial undoing. So-called Slow Cinema has never been suited to mainstream audiences, not in its emergence with filmmakers such as Chantal Akerman, Michelangelo Antonioni, Ingmar Bergman, and Yasujiro Ozu, and certainly not among viewers of today’s hyperactive blockbusters. Warner Bros. made Blade Runner 2049 for $150 million, probably much more, but their losses will be short-term if the film resonates as Scott’s did—over several years, after repeated viewings, and some serious reflecting. That sort of reconsideration is necessary, as each long take that concentrates on K’s measured behavior presents the viewer with the gift of time: to think about the consequence of the scene, to absorb the artistry loaded into each shot, and to question the nature of these characters.

Some have found Blade Runner 2049 just as elusive as Scott’s original. To be sure, Villeneuve leaves the material open for debate (although, I feel the film is less ambigous than many claim). Audiences may ask whether Deckard is human. He has aged, but then so has Sapper Morton, a replicant without a predetermined lifespan. And what about K? Many viewers somehow doubt the replicant status of the film’s protagonist. Through it all, the persistent question about what it means to be human lingers, until eventually “human”—that qualifier of validated life—becomes a troublesome, almost hateful word with both historical and modern-day parallels. Beyond the rigorous plotting and deceptive characters, the film will surely demand that its entrenched fanbase return to this intricate world, which never betrays the 1982 film, but rather builds upon its mythology, probes deeper into the bleak future, and provides a superior emotional experience. That Villeneuve achieves such a cerebral and even touching picture, while also accomplishing an uncommonly sublime production, marks Blade Runner 2049 as a landmark in the science-fiction genre.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review