Blackthorn

By Brian Eggert |

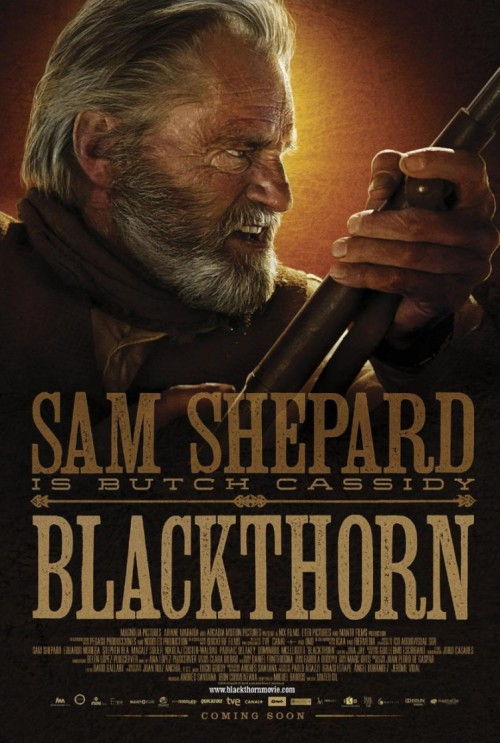

When George Roy Hill freeze-framed that iconic last shot of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, he saved his audience from having to watch our heroes meet their demise. But according to first-time feature director Mateo Gil’s new Western, Blackthorn, Butch and Sundance survived the 1908 shootout with Bolivian authorities. Sundance would die shortly thereafter, but Butch would live another two decades in anonymity under the name James Blackthorn, raising horses on a quiet Bolivian homestead tucked away from the world. Played by Sam Shepard in an intangibly charismatic, grizzled performance, the Western hero has one last adventure here, although there’s more to Gil’s narrative than the cheery, fun-loving shootouts and armed robberies from the 1969 film.

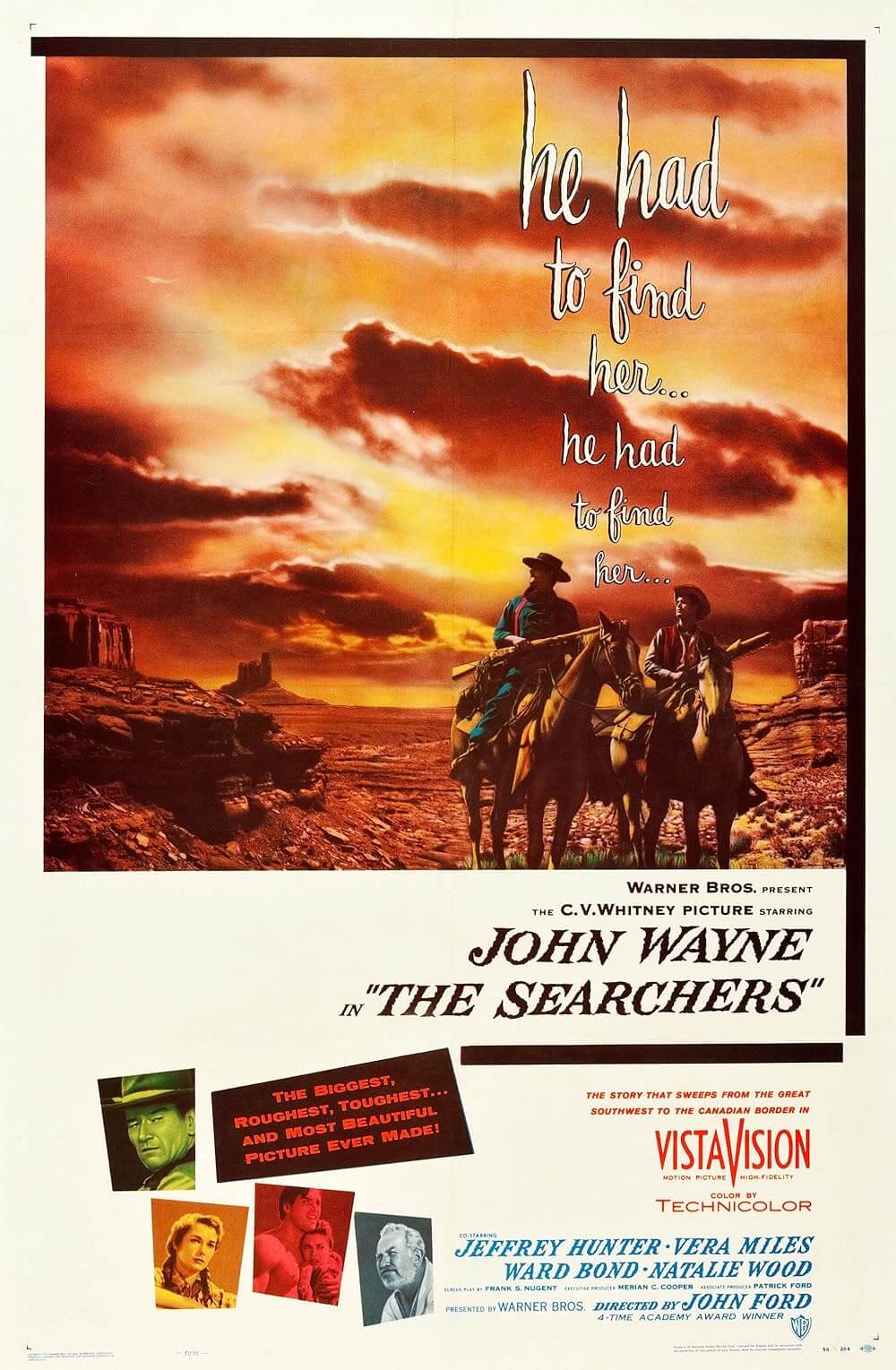

The script by Gil, acclaimed writer of Agora and The Sea Inside, finds Blackthorn living a quiet life against the gorgeous Bolivian backdrop, as shot by cinematographer Juan Ruiz Anchia. Anchia avoids transforming the landscape into one evocative of John Ford’s archetypal Western vision of Monument Valley but breathes unique life into misty mountains and treacherous flats. It’s not a typical Western vista, but it’s beautiful. On a spot of green land, the utterly human Blackthorn finds occasional company in Yana (Magaly Solier), yet plans to leave for America soon. He’s been writing his nephew, who could be his son, as flashbacks suggest the romance between Sundance (Padraic Delaney) and Etta Place (Dominique McElligott) brought offspring, but that the younger Butch (Nikolaj Coster-Waldau) could have fathered the child nonetheless. The man named Blackthorn withdraws his savings of six thousand from the bank and intends to head north by horseback and meet his only remaining family.

Before his journey even begins, however, Blackthorn is waylaid by Spanish mining engineer Eduardo (Eduardo Noriega, from The Devil’s Backbone), who is on the run after robbing the mine of a crooked local tycoon. When Blackthorn’s horse runs off and with it his savings, he’s forced to entertain Eduardo’s claims to a hidden fortune. Eduardo promises him a share should he lead him out of the harsh desert, and so together, they head out in search of Eduardo’s stash. But Butch’s longstanding adherence to his heyday’s moralized version of criminal enterprise has left him blind to the ruthlessness of his surroundings. Meanwhile, Stephen Rea (The Crying Game) plays ex-Pinkerton Mackinley, ruined (and turned to drink) from his widely voiced suspicion that Butch and Sundance weren’t killed in 1908. His eventual discovery of the truth brings a surprising and thoughtful response.

Flashbacks to Butch and Sundance in their prime never feel congruous to the material set twenty years later, as we’re constantly comparing Coster-Waldau and Delaney to Paul Newman and Robert Redford, which, as you can imagine, is no comparison at all. Fortunately, Shepard contains the same wise, internal, searching air he had in Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven. Complete with a full beard and the kind of dusty gray mane that older men wish for, the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright has an indefinable presence, achieving the embodiment of a rugged Western man of experience. Shepard also sings in the film, calling out “Sam Hall” with a deep resonance to the pain behind the lyrics (“Damn your eyes, Sam Hall!”). Though some elements of the plot may not work in the bigger picture, or against the enduring legend of Butch and Sundance, the film is worth seeking out for Shepard and Rea’s performances.

Had Gil simply omitted certain details from Blackthorn and not identified the story as one about Butch Cassidy, I think it would be a better film. Given the iconic status of George Roy Hill’s classic, an audience will constantly compare this film to that one, and frankly, it fails to hold up. But if the story remained the same—about a man reflecting on his past in light of his present mistakes—and resolved to be about a less recognizable Western outlaw, it would be an engaging tale, without a hint of reservation. Alas, an audience must accept that Gil’s vision of Butch Cassidy differs from the legend ingrained into our moviegoer awareness, and then embrace his “what if” meditation on the twilight of a Western myth. If you can overcome that conceptual setback, there’s plenty of Western innovation in this unique setting for any fan of the genre to savor.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review