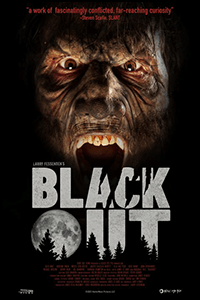

Blackout

By Brian Eggert |

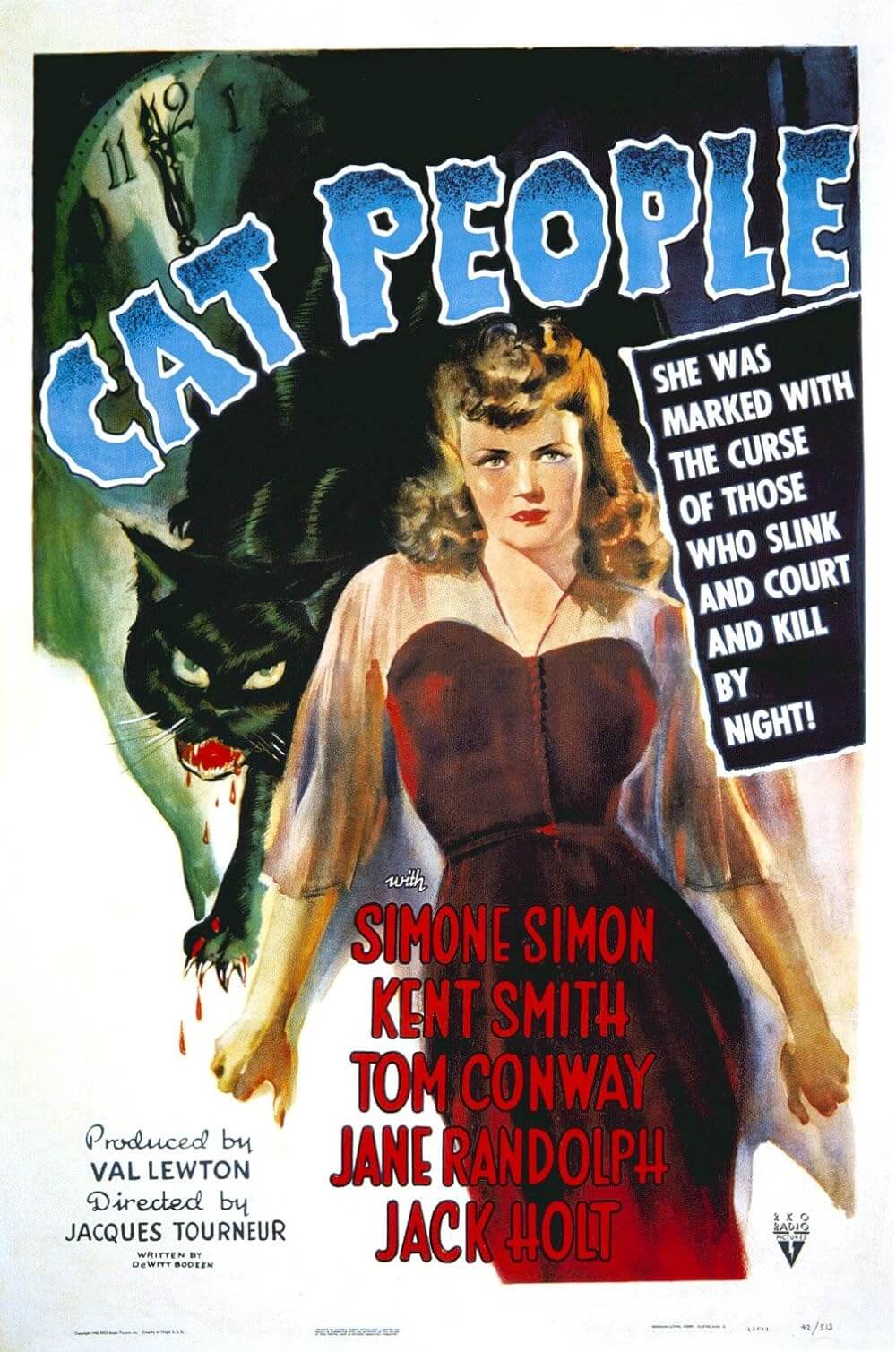

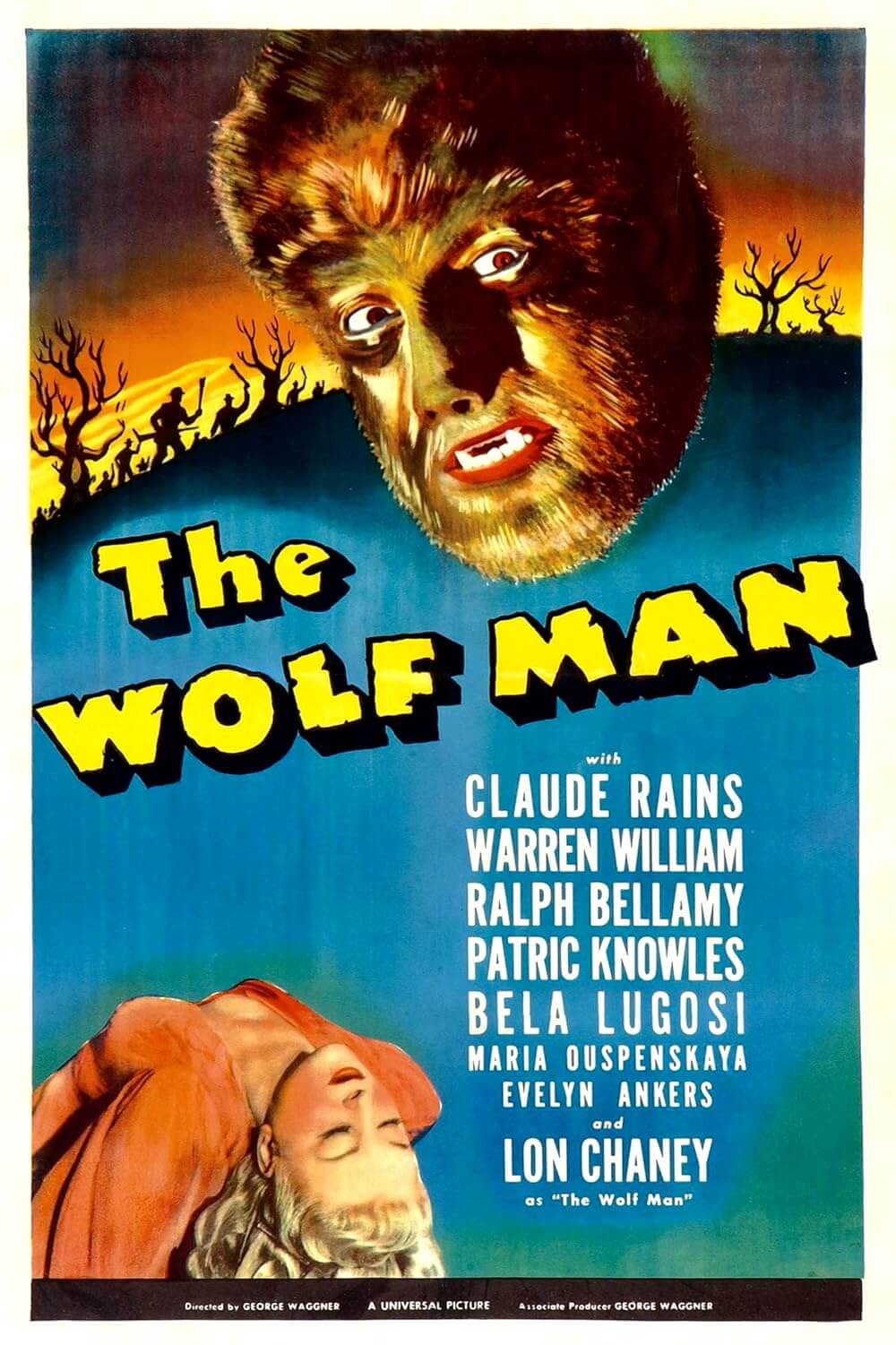

Larry Fessenden has made a career out of demonstrating that genre movies have the same capacity to confront social issues as serious dramas. The defiantly independent filmmaker behind the New York-based production company Glass Eye Pix, Fessenden uses horror in allegorical terms, applying his scrappy, low-budget approach to sometimes traditional motifs. He created a modern Dr. Frankenstein in No Telling (1991), an early career feature that involves a mad scientist experimenting on animals, thereby addressing issues from the unethical treatment of animals to environmentalism. His breakout, Habit (1997), explored the alienation and self-destructiveness of an alcoholic loner within a vampire story. Years later, he returned to Mary Shelley territory with Depraved (2019) and took on the physical and psychological toll of combat and PTSD on US soldiers. Fessenden’s latest, Blackout, continues his tendency to reframe classic monsters with contemporary concerns, using a werewolf movie in the style of The Wolf Man (1941) in a story about matters of land development, the exploitation of migrant workers, and, of course, personal demons.

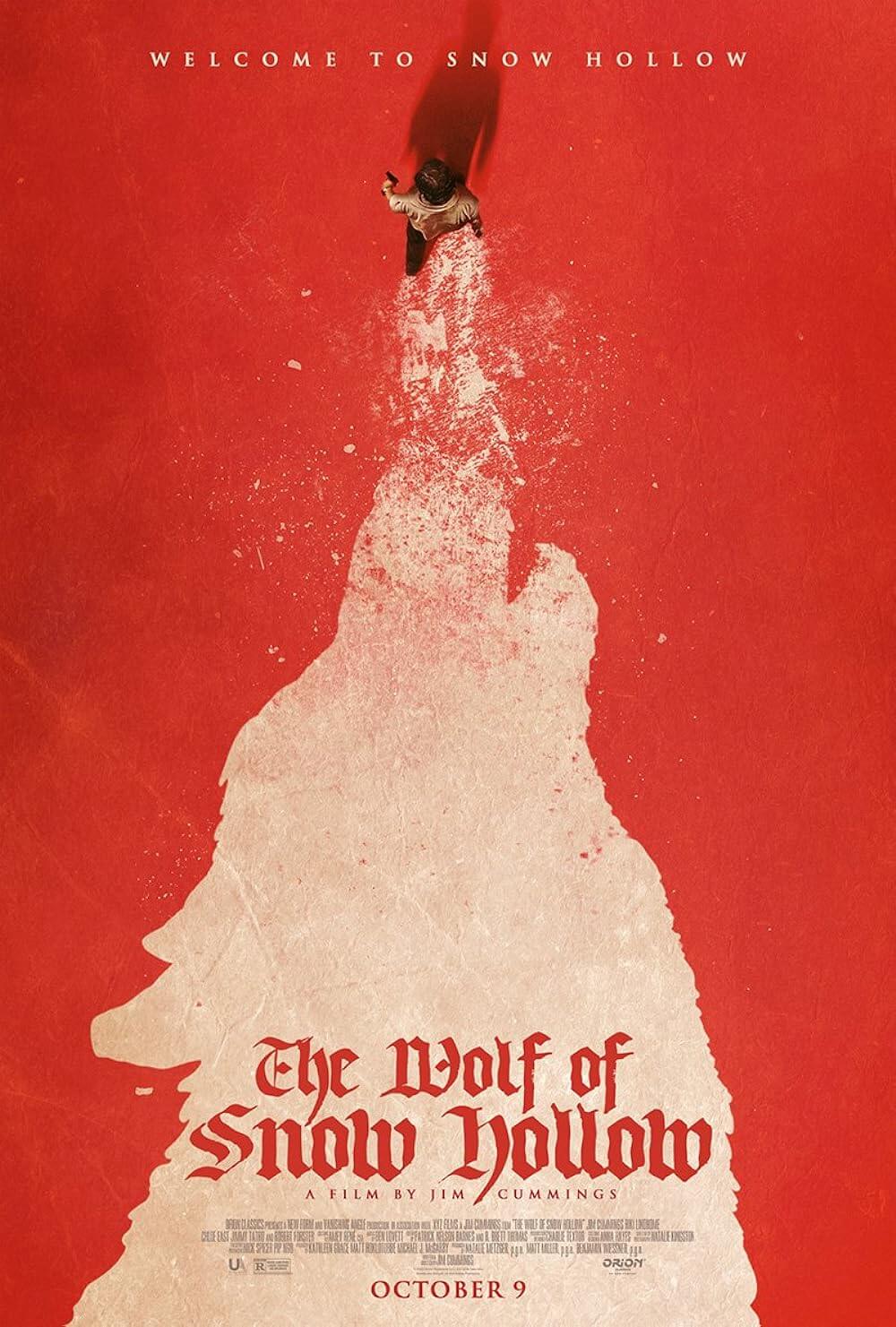

Blackout boasts a refreshingly classical werewolf look that counters recent offerings, most of which involve humans transforming into bipedal wolf creatures. The trend was popularized by a series of movies in the early 1980s that tried to outperform each other with their elaborate practical transformations—see 1981’s An American Werewolf in London and The Howling, and 1984’s The Company of Wolves. Effects wizards have been paying homage ever since. Cases where the main character transforms into a monster resembling the original Wolf Man from Universal Pictures, a clothed man-beast played by Lon Chaney Jr., remain far less frequent. Although exceptions include Jack Nicholson in Wolf (1994) and Benicio del Toro in The Wolfman (2010), most contemporary werewolf movies opt for a full lycanthropic transformation into a creature resembling an animal (see the Twilight and Underworld franchises), adding an element of spectacle into the presentation. So Fessenden’s adoption of a classical wolf-man design in Blackout gives the film a certain throwback appeal.

Following an old B-movie trope that suggests horror needs a death or nudity in the first few minutes to hook the viewer, Blackout features both. With that out of the way, the story takes place in a sleepy Pacific Northwestern town called Talbot Falls, a winking reference to Larry Talbot, the name of the original Wolf Man character from George Waggner’s film. The local cops even have badges that resemble pentagrams, “The mark of the werewolf,” according to the original movie. The story centers on Charley, played by Alex Hurt, son of the late actor William Hurt. The young Hurt emotes in a way similar to his father, including his uncanny intensity and a weariness behind his eyes, suggesting a deep-seated pain he’s masking, albeit unsuccessfully. The truth about Charley: he’s a werewolf. Hurt plays this artist and struggling alcoholic with the gravity befitting someone teeming with guilt and uncertainty over transforming into a monster and slaying innocents, only to wake up bloodied and with no memory of what happened.

Charley has spent the last month holed up in a motel, frantically painting and mourning the end of his relationship with Sharon (Addison Timlin). A series of killings has made the townsfolk jumpy, their fears stoked by Hammond (Marshall Bell), a local land developer and community leader. Hammond slings unfounded suspicions about an immigrant worker, Miguel (Rigo Garay), who witnessed the attack on two of the victims. But Hammond has his own troubles concerning a new resort project that may have falsified environmental contamination records. Most in Talbot Falls have no idea about the developer’s shady dealings, except Charley, whose late father (seen in candid photos of William Hurt) worked with Hammond. The few who know about Hammond don’t care because his contracts in Talbot Falls mean steady work, and that kind of apathy frustrates Charley. While he enlists an attorney (Barbara Crampton) to find evidence against Hammond, Charley makes the rounds about town, apologizing for the emotional damage he’s caused and planning to end his life with a silver bullet.

Charley has spent the last month holed up in a motel, frantically painting and mourning the end of his relationship with Sharon (Addison Timlin). A series of killings has made the townsfolk jumpy, their fears stoked by Hammond (Marshall Bell), a local land developer and community leader. Hammond slings unfounded suspicions about an immigrant worker, Miguel (Rigo Garay), who witnessed the attack on two of the victims. But Hammond has his own troubles concerning a new resort project that may have falsified environmental contamination records. Most in Talbot Falls have no idea about the developer’s shady dealings, except Charley, whose late father (seen in candid photos of William Hurt) worked with Hammond. The few who know about Hammond don’t care because his contracts in Talbot Falls mean steady work, and that kind of apathy frustrates Charley. While he enlists an attorney (Barbara Crampton) to find evidence against Hammond, Charley makes the rounds about town, apologizing for the emotional damage he’s caused and planning to end his life with a silver bullet.

Viewers expecting a straightforward werewolf movie with sensationalized killings and horror-centric thrills may be disappointed. Although Blackout boasts a few jarring monster images and a shock or two, achieved mostly with inexpensive practical effects, Fessenden isn’t interested in delivering a horror programmer. Instead, the movie is a portrait of America seen through the perspective of an outsider, who is so ruined by his disenchantment that he’s given to drinking and lashing out at those close to him. Exploitative land deals, racist cops, militia groups taking the law into their own hands, and discriminatory leaders have caused Charley to retreat into his artist’s life. His inability to function as a productive member of Talbot Falls is symptomatic of people who feel powerless in the face of injustice. “You got the haunt in you,” Miguel tells Charley. But he doesn’t connect that Charley’s demon is the “hombre lobo” suspected of terrorizing the town.

Serving as the writer, director, producer, and editor, Fessenden finds a clever form-follows-function excuse to avoid showing elaborate werewolf transformations in his film. After the two local cops (Ella Rae Peck and Joseph Castillo-Midyett) discuss the German concept of “umwelt,” a word for how one’s environment shapes one’s perspective and how one sees the world, the director has an excuse to take us into Charley’s mind for his transformations. Rather than showing an elaborate change with rubbery effects or CGI, both of which would strain Fessenden’s usual budgetary limitations, the director opts for inspired animated sequences that look like paintings come to life. They show how Charley, the painter, sees himself through his art of choice. Elsewhere, Collin Brazie’s handheld cinematography adds a naturalistic style, while werewolf-cam visual effects recalling the wolf sequences in Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) give the attack scenes some frenetic energy.

While Blackout’s production values may look negligible even by the standards of today’s booming indie horror market, Fessenden draws excellent performances out of his cast of familiar faces. Genre veterans Bell and Crampton join Joe Swanberg, James Le Gros, Kevin Corrigan, and Michael Buscemi for a feature that might be laughable in another filmmaker’s hands. Fortunately, Fessenden brings narrative gravitas to a story that, not unlike Habit or many of his other features, is less about monster thrills than the complex central performance. Hurt sells every moment of the film, even if his facial prostheses don’t belong in a conversation about the best-looking screen werewolves. Hurt’s wounded persona and Fessenden’s portrait of Talbot Falls as a stand-in for America make for a compelling watch in a rare, worthy werewolf movie about a familiar condition of existential despair.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review