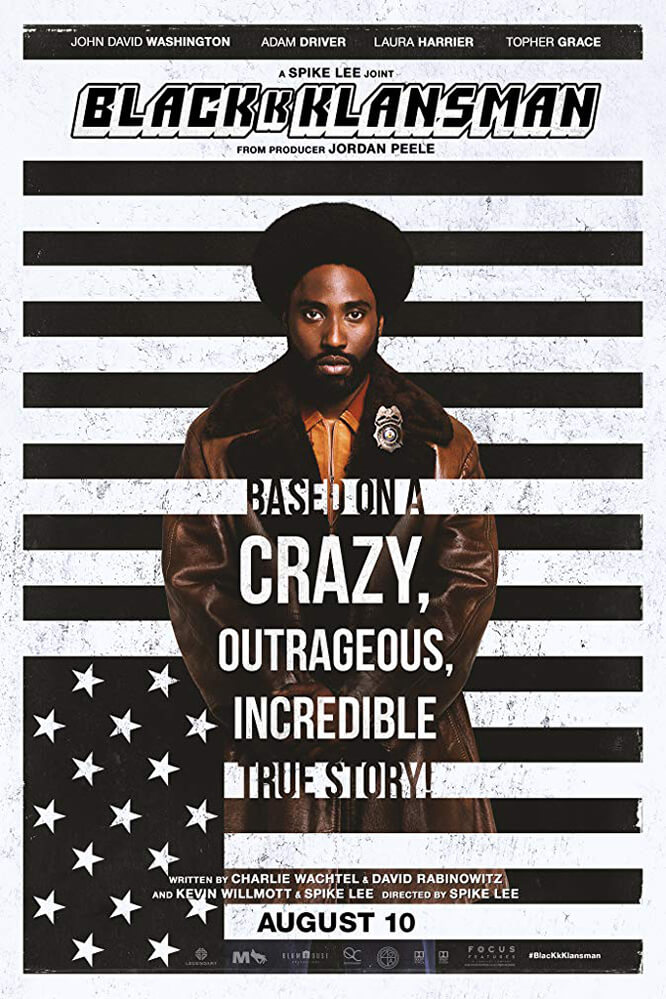

BlacKkKlansman

By Brian Eggert |

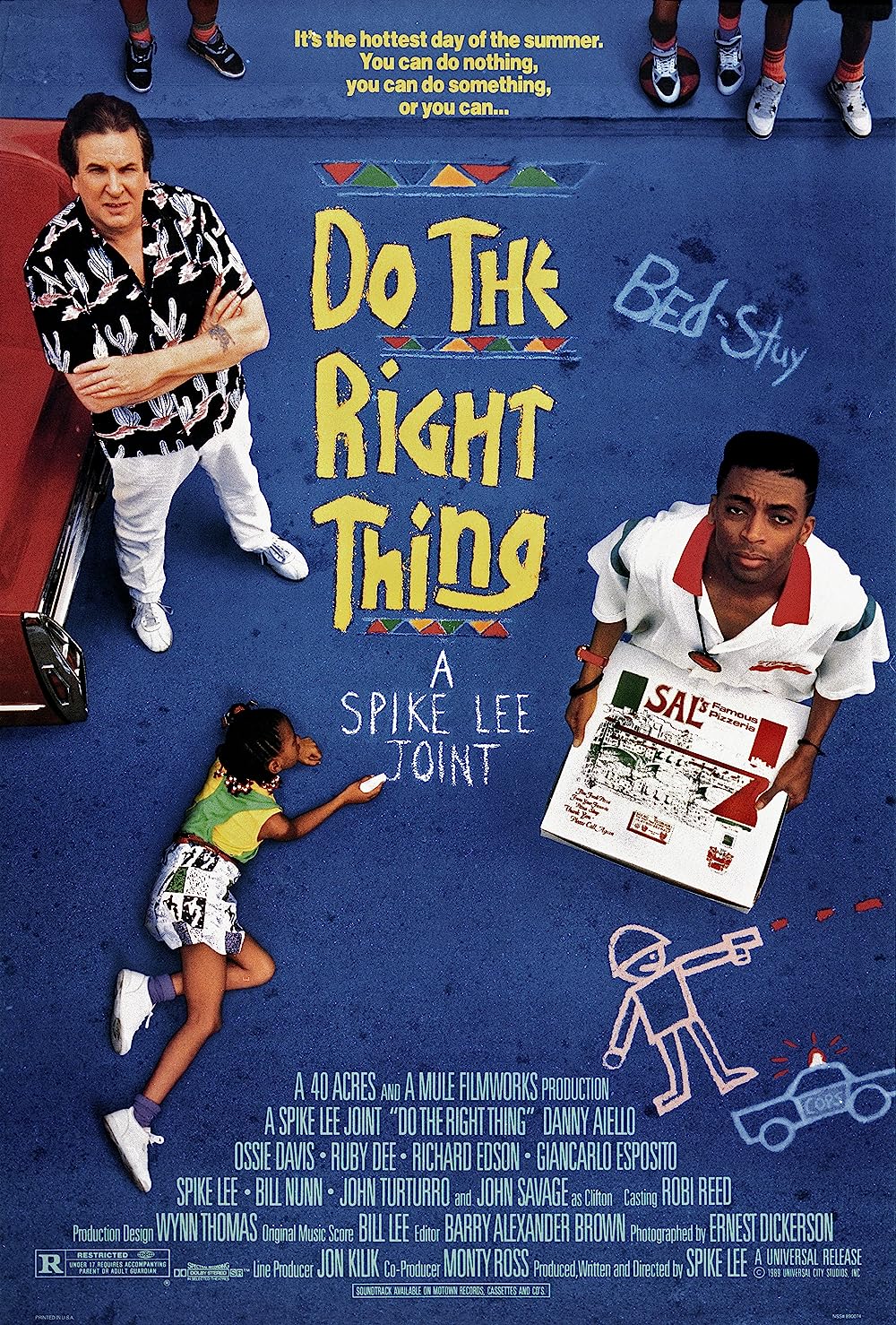

Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman opens, by no coincidence, almost a year after the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, North Carolina, where hundreds of protesters from various white supremacist groups, many of them carrying swastikas or Ku Klux Klan imagery, demonstrated against the city’s order to remove Confederate monuments from public spaces. They shouted racial slurs against Jews and people of color, used the Nazi slogan “blood and soil,” and carried torches in a march for white supremacy. In the chaos, Heather Heyer lost her life after a member of the white nationalist movement drove his car into a crowd of counter-protesters. BlacKkKlansman is a subversive wake-up call to Americans—who love to declare their country the greatest in the world, despite the U.S. facing division, bigotry, violations of basic civil rights, and rampant intolerance from hate groups—to face the reality that their country does not supply liberty and justice for all, and instead remains in a state of crisis. By telling the true story of Ron Stallworth, a Black detective in the Colorado Springs Police Department who infiltrated the Ku Klux Klan, Lee’s undeniably political statement uses the semblance of a detective film to weave a thread through the Confederacy, the lasting presence of hate groups in the United States, the rally in Charlottesville, and the presidency of Donald Trump, who refused to condemn white nationalism. Lee’s most purely entertaining film since Inside Man in 2006, BlacKkKlansman has a timeliness that taps into an imperative national conversation, more than any film since Do the Right Thing (1989).

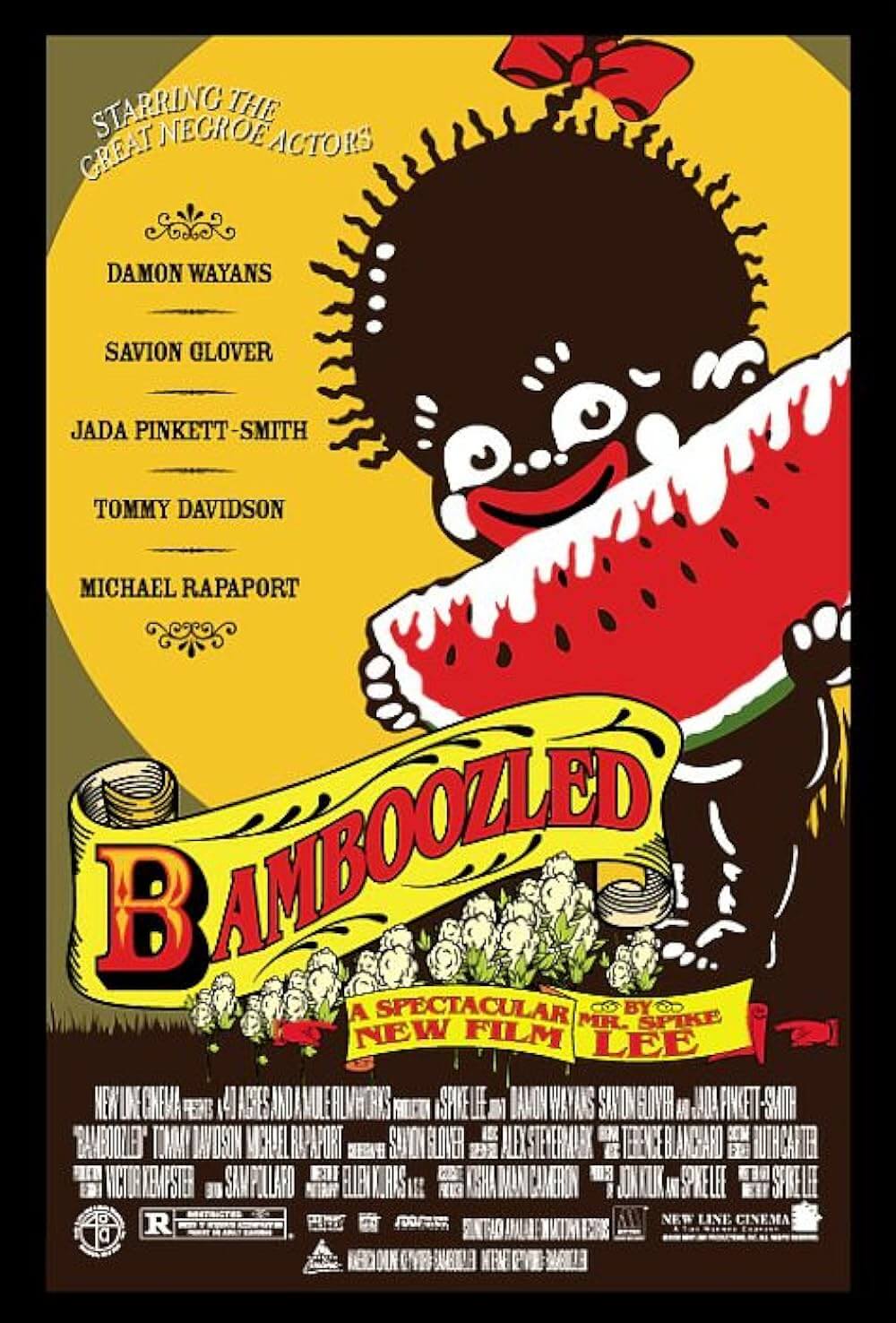

Based on Stallworth’s 2014 memoir, the film adheres to the director’s interest in Black history, demonstrated in Malcolm X (1992) and Miracle at St. Anna (2008), combined with his recontextualization of history through a modern commentary on the Black experience, as seen in his underrated Bamboozled (2000). When it debuted at the Cannes Film Festival earlier this year, BlacKkKlansman received the Grand Prix, in spite of its decidedly American contexts, because the significance of the subject matter and the filmmaking find Lee at his best. At the same time, BlacKkKlansman is the kind of story that doesn’t seem possible, or even probable. He might be accused of applying an almost cartoonish touch if not for Ron Stallworth’s autobiographical novel. The book details how Stallworth, despite his race, subverted the KKK’s ranks and became a card-carrying member. He fooled David Duke, a former Grand Wizard, in their conversations on the phone (played with dopey arrogance by Topher Grace in the film), and in a shocking turn, he had to serve as Duke’s bodyguard during his visit to Colorado Springs. And yet, the setup remains true, and its outlandishness only adds to the poetry and significance of Lee’s statement.

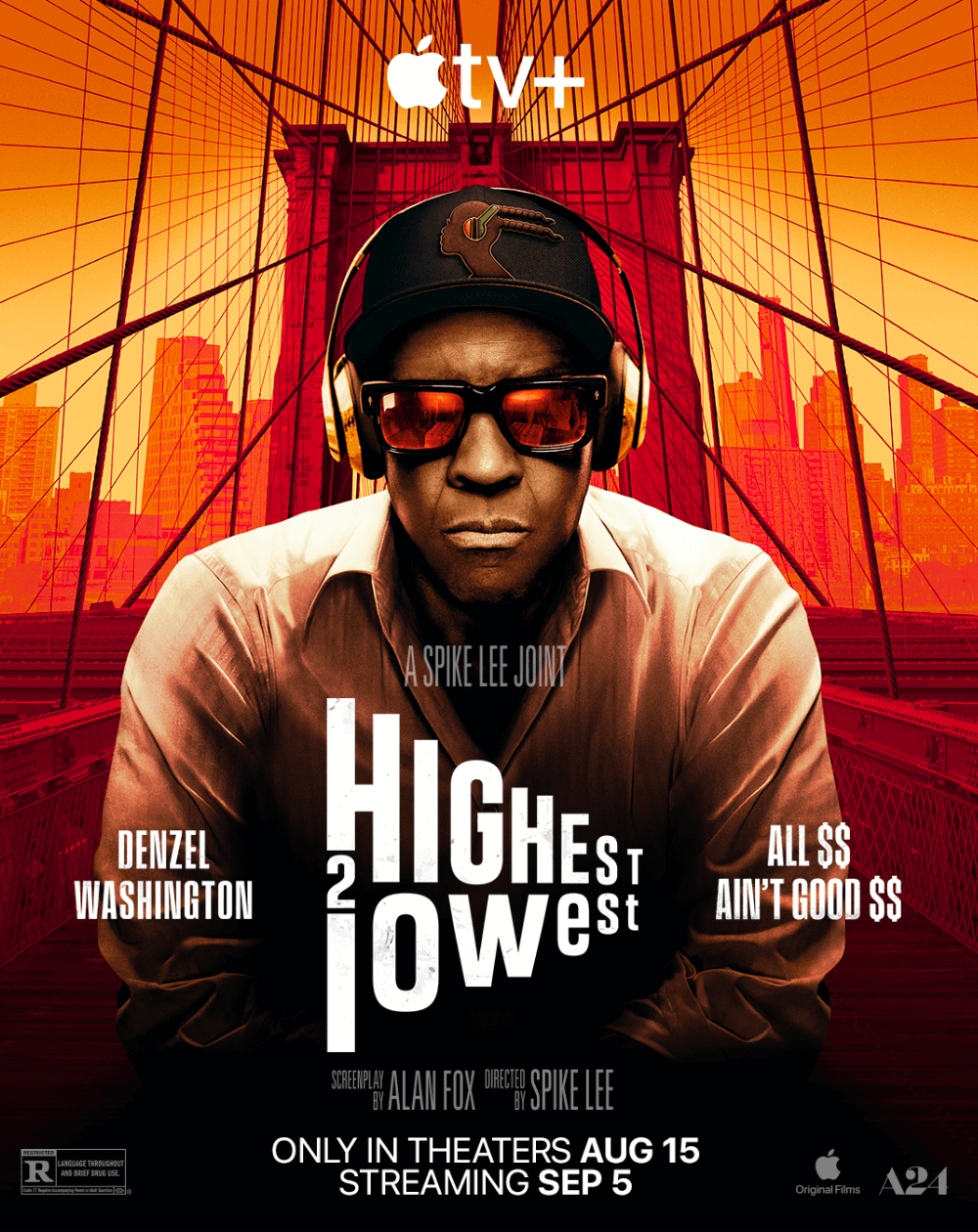

Rather than depict Ron as an unsung hero of Black history, Lee delivers a policier in a gritty, structurally familiar style, reminiscent of certain elements in Summer of Sam (1999) or Inside Man. He hits the requisite beats of a detective story, where Ron, played with incredible charisma by John David Washington (son of Lee’s frequent collaborator, Denzel), begins an undercover case that forces him to question his allegiances. A relatively inexperienced young actor, Washington has all the screen magnetism and capacity for intricacy and subtlety as his father. After an early assignment from his superior (Robert John Burke) finds him undercover at a Black Panther rally, trying to scope out whether the Black citizens of Colorado Springs will be brainwashed by a powerful speaker, Kwame Ture (Corey Hawkins), Ron realizes that his department’s prejudices have led to undue suspicion of a civil rights group. On a whim, perhaps out of defiance to his Black Panther assignment, Ron responds to a KKK newspaper ad and connects by phone with Walter (Ryan Eggold), the leader of the Colorado Springs chapter of the KKK, dubbed “the Organization” by its members. He leads an undercover investigation that involves sending his white partner, Flip Zimmerman (Adam Driver), to be the face to his voice, and uncover their violent intentions.

Rather than depict Ron as an unsung hero of Black history, Lee delivers a policier in a gritty, structurally familiar style, reminiscent of certain elements in Summer of Sam (1999) or Inside Man. He hits the requisite beats of a detective story, where Ron, played with incredible charisma by John David Washington (son of Lee’s frequent collaborator, Denzel), begins an undercover case that forces him to question his allegiances. A relatively inexperienced young actor, Washington has all the screen magnetism and capacity for intricacy and subtlety as his father. After an early assignment from his superior (Robert John Burke) finds him undercover at a Black Panther rally, trying to scope out whether the Black citizens of Colorado Springs will be brainwashed by a powerful speaker, Kwame Ture (Corey Hawkins), Ron realizes that his department’s prejudices have led to undue suspicion of a civil rights group. On a whim, perhaps out of defiance to his Black Panther assignment, Ron responds to a KKK newspaper ad and connects by phone with Walter (Ryan Eggold), the leader of the Colorado Springs chapter of the KKK, dubbed “the Organization” by its members. He leads an undercover investigation that involves sending his white partner, Flip Zimmerman (Adam Driver), to be the face to his voice, and uncover their violent intentions.

As BlacKkKlansman proceeds, it becomes a sort of buddy cop film, in which Ron and Flip clash over the purpose of their investigation. Ron sees taking down the KKK as a passion project of social and legal justice, whereas Flip sees the assignment as just another case. Flip, a secular Jew that hides his religion, sees the job as a professional assignment, nothing more. Until, of course, he begins to hear the rhetoric and understand the hateful philosophy of resident Klansmen, including Walter, the buffoonish Ivanhoe (Paul Walter Hauser), and the ever-suspicious Felix (Jasper Pääkkönen). Flip meets with the KKK under Ron’s name, but Felix remains suspicious and accuses him of being Jewish in several suspenseful moments that threaten to expose the operation, and Flip, should Felix discover his secret. Flip’s arc is just as involving as Ron’s, as he questions his heritage and self-suppressed Jewish identity when confronted by the KKK. Driver brings the role restraint and gravity, turning their partnership into a complex portrait of Black and white officers working together on the same mission, while never descending into a kitschy buddy scenario of ‘80s cop movies like 48 Hrs. (1982) or Lethal Weapon (1987). Rather, similar to another 2018 film, Boots Riley’s satire Sorry to Bother You, Lee acknowledges that many African Americans take on performative roles and, in a sense, feel pressure to go undercover in the presence of white people.

Diverting from Stallworth’s book, Lee and his fellow screenwriters (Charlie Wachtel, David Rabinowitz, Kevin Willmott) introduce a love interest for the film’s hero. The passionate young activist Patrice (Laura Harrier) oversees the local Black student union, and she maintains some prejudices against the police, given their history of shooting down people of color in the street or, in one scene, a traffic stop that turns frightening and invasive. Patrice serves as a thoughtful device in both the narrative and plot. She challenges the college-educated Stallworth’s ideas about race and power, demanding that he fight to grant power to all people, not just a single race. She also becomes a target for Felix and his wife, who set out to bomb and thus silence Patrice for emboldening Black voices in Colorado Springs. But as a rare strong female character in a Lee film, Patrice’s best moment is when she questions her romantic relationship with Ron, who refuses to accept that all police are racist. He remains hopeful that his presence on the force could prove that not all police are the type she fears, while she cannot betray her convictions and experience by staying with him. It’s a moment that acknowledges the preconceptions on both sides, and asks for the conversation to continue.

Lee’s portrait of KKK members reveals the hatred driving their mission with a tone that borders on surreal, or perhaps it just feels that way given their intolerably intolerant perspective. Take a scene between Felix and his wife, the cheery and particularly hateful homemaker Connie (Ashlie Atkinson), lying in bed as they talk about how fighting for white power has enriched their marriage, revealing the racist ideology stitched into the fabric of their lives. The moment echoes familiar scenes where couples talk about their hopes and dreams in an intimate setting, but given the nature of their conversation, the scene is horrifying and sardonic. Later, when Flip, posing as Ron, is finally inducted into the Klan, the group celebrates by watching D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915). Lee juxtaposes their rowdy screening, complete with hoots and cheers for the film’s notoriously racist content, with a speech given by activist Jerome Turner (Harry Belafonte) in Patrice’s home. Belafonte delivers a heartrending account of when, as a young man, he witnessed the murder of the real-life Jesse Armstrong, an African American teenager with mental disabilities who was railroaded through the courts before being lynched, mutilated, and burned on the streets by a cheering white crowd in Waco, Texas.

Lee’s portrait of KKK members reveals the hatred driving their mission with a tone that borders on surreal, or perhaps it just feels that way given their intolerably intolerant perspective. Take a scene between Felix and his wife, the cheery and particularly hateful homemaker Connie (Ashlie Atkinson), lying in bed as they talk about how fighting for white power has enriched their marriage, revealing the racist ideology stitched into the fabric of their lives. The moment echoes familiar scenes where couples talk about their hopes and dreams in an intimate setting, but given the nature of their conversation, the scene is horrifying and sardonic. Later, when Flip, posing as Ron, is finally inducted into the Klan, the group celebrates by watching D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915). Lee juxtaposes their rowdy screening, complete with hoots and cheers for the film’s notoriously racist content, with a speech given by activist Jerome Turner (Harry Belafonte) in Patrice’s home. Belafonte delivers a heartrending account of when, as a young man, he witnessed the murder of the real-life Jesse Armstrong, an African American teenager with mental disabilities who was railroaded through the courts before being lynched, mutilated, and burned on the streets by a cheering white crowd in Waco, Texas.

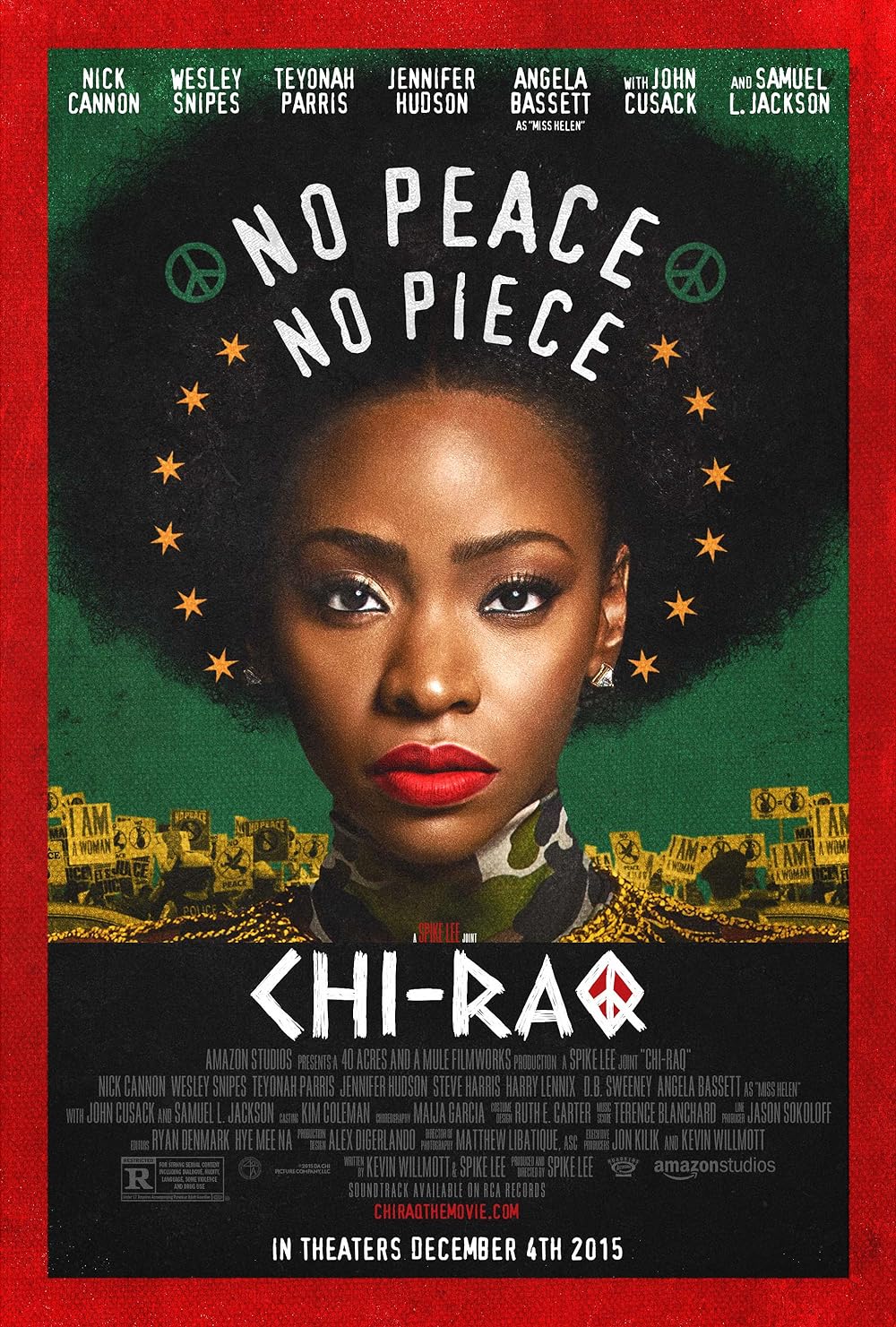

As Lee cuts back and forth between Flip’s induction into the KKK and Belafonte’s sobering speech, the director once again creates a playful, emotionally challenging, and wholly intentional tonal imbalance. Like many of Lee’s films, BlacKkKlansman is a lot of things at once, volleying between styles and modes of expression that demonstrate his knowledge of history, aesthetics, and cinema. On the surface, Lee and cinematographer Chayse Irvin shot on 35mm film stock and gave the image a grainy, ’70s-style color palette, making BlacKkKlansman appear like an essential crime drama in the vein of Jack Hill, Sidney Lumet, or William Friedkin. But through editing, split-screens, and sometimes tongue-in-cheek asides, Lee turns his film into a post-modern pastiche. His brand of pastiche demands that the viewer engage with the material and deconstruct it. Some critics and moviegoers have critiqued Lee’s methods as too derivative, his characters too obviously mouthpieces for his message, his statements too didactic, and his tonal shift as too messy. But then, Lee’s originality as an artist begins with this unique blend of stylistic flourishes. He’s never resisted making statements, never disguised his influences, and intentionally alters the pitch of his films to keep viewers on edge, forcing them to think and reconsider what they’re being shown and why. It’s these tonal shifts that have kept audiences away from his most insightful and important, but wholly underappreciated films like Bamboozled and Chi-Raq (2015). They’re also the signature of his work, which makes it baffling when anyone complains about such basic elements of a Spike Lee joint.

The policier elements of BlacKkKlansman are just the majority component in a larger discussion taking place within the film, as evidenced by the bookend segments. Consider the opening, which begins with two sequences not directly connected to Ron Stallworth’s case. The first shot of Lee’s film is the famous scene from Gone with the Wind (1939) that finds Scarlett O’Hara rushing through a massive crowd of wounded soldiers, until the shot pulls back to reveal a Confederate flag that, in the context of the scene, was meant to evoke a sense of mourning and patriotism, but today proves damaging. From this, Lee cuts to Dr. Kennebrew Beaureguard (Alec Baldwin, unofficial Trump lampooner), who records a vitriolic rant that warns of a Jewish conspiracy to incite miscegenation between the superior white race and the inferior African American population. Lee designed these first minutes to set the ideological stage of America as a country with a history of institutionalized racism. The timeline, then, follows Ron Stallworth’s story from 1972, after which the film closes with actual footage from the Unite the Right rally and the ensuing violence, as well as footage from Trump’s refusal to condemn the rally, and Duke’s open support of Trump. Lee’s film reminds the viewer with the comic message, “Dis joint is based on some fo’ real, fo’ real sh*t,” and in doing so, he urgently connects the distant, regretful past to our current situation.

The policier elements of BlacKkKlansman are just the majority component in a larger discussion taking place within the film, as evidenced by the bookend segments. Consider the opening, which begins with two sequences not directly connected to Ron Stallworth’s case. The first shot of Lee’s film is the famous scene from Gone with the Wind (1939) that finds Scarlett O’Hara rushing through a massive crowd of wounded soldiers, until the shot pulls back to reveal a Confederate flag that, in the context of the scene, was meant to evoke a sense of mourning and patriotism, but today proves damaging. From this, Lee cuts to Dr. Kennebrew Beaureguard (Alec Baldwin, unofficial Trump lampooner), who records a vitriolic rant that warns of a Jewish conspiracy to incite miscegenation between the superior white race and the inferior African American population. Lee designed these first minutes to set the ideological stage of America as a country with a history of institutionalized racism. The timeline, then, follows Ron Stallworth’s story from 1972, after which the film closes with actual footage from the Unite the Right rally and the ensuing violence, as well as footage from Trump’s refusal to condemn the rally, and Duke’s open support of Trump. Lee’s film reminds the viewer with the comic message, “Dis joint is based on some fo’ real, fo’ real sh*t,” and in doing so, he urgently connects the distant, regretful past to our current situation.

Lee’s film calls for audiences to recognize the state of things and make necessary connections throughout history, suggesting that, after Charlottesville, Trump has drawn his line in the sand. Now so has Lee, whose last shot of BlacKkKlansman rests on an upside-down American flag—the symbol of a country in distress. However serious the film’s ideas, Lee has nevertheless created one of his most accessible and enjoyable entertainments, a lightning bolt into the zeitgeist whose thunder echoes across centuries of American history and film history. It’s hilarious, thoughtful, frightening, insightful, exciting, scary, germane, and necessary. Besides making a star out of Washington, the director’s masterful juggling of riotous humor, the tensions and tropes cop films, and layered characters gives way to a vital motion picture for our times, and an incredible demonstration of his skill. If the film seems to adopt a crazy pitch, functioning on an aesthetic level of heightened reality, it’s because, from Lee’s perspective, these are crazy times. Lee’s message in the film is not just a fascinating episode from history; it’s a notice that this seemingly impossible past exists in our present culture.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review