Blackhat

By Brian Eggert |

The misdeeds of cyber-criminals are not inherently cinematic. They sit at their computers, surrounded by servers and monitors, their workstations covered with fast food wrappers and action figures. There’s usually a television in the background playing some strange anime, and sometimes there’s even a Guinea Pig named Cashew nearby. The hacker types away on their keyboard and, after inputting a few lines of code, somehow navigates their way into the Pentagon, or some other such impregnable hub, to extract information or cause mayhem. Watching someone perform such a feat has never been very interesting for moviegoers, and entertainment ensues only when someone chases the hacker, or the hacker tries to escape physical capture. The rest is technobabble best left offscreen. For example, the most interesting scenes in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo had little to do with Lisbeth Salander researching or hacking private networks; rather, they involved her violent and sordid interactions with other human beings.

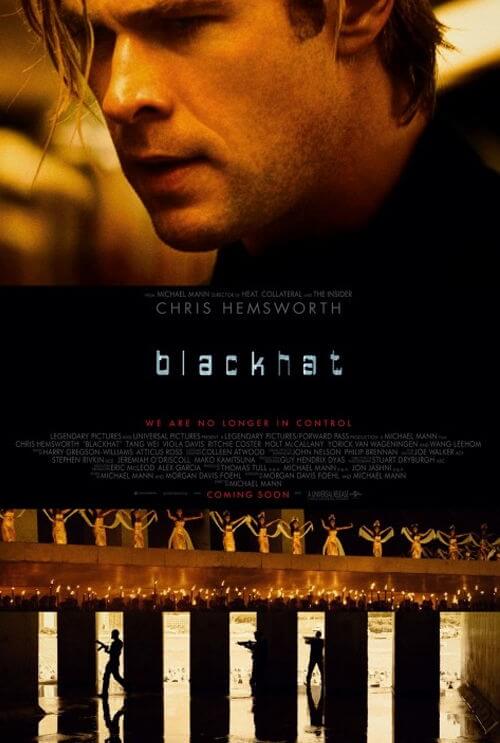

Fortunately, Michael Mann’s cyber-thriller Blackhat interrupts otherwise dull sequences of reading code with several chase scenes, shootouts, and a slow-burning romance between international stars Chris Hemsworth and Wei Tang (from Lust, Caution). Recently named People magazine’s “Sexiest Man Alive”, Hemsworth stars as Nicholas Hathaway, the world’s most dangerous hacker, also known as a “blackhat”. Just thinking about the buff, 6′ 3″ star of Thor playing a computer whiz is almost unintentionally funny, but Mann concocts a clever backstory for the character that transforms the role, and thus the film as a whole, into one closely related to his previous work. When the film opens, Hathaway has been rotting in prison for years, but he’s brought out when an unknown, malevolent hacker modifies one of Hathaway’s older code strings and then uses it to detonate a Chinese nuclear power plant and manipulate the stock market.

Impeccably researched by Mann, per usual, and scripted by Morgan Davis Foehl, the film follows a Chinese cyber defense authority Chen Dawai (pop-star Wang Leehom) who liaises with FBI agent Carol Barrett (Viola Davis) to find who they believe is a cyber-terrorist without a specific motive. To do this, Dawai recommends that they rescue his former MIT classmate, Hathaway, from a 15-year prison sentence to assist. Hardened by his time inside, Hathaway emerges buff and focused, having learned to control his mind and body behind bars to stay sharp. Mann has long been interested in the effects of prison on his criminal characters. This preoccupation goes back to his early made-for-TV movie about prison life, The Jericho Mile (1979), and continued in both Thief (1982) and Heat (1995). In each film, Mann explores the unwavering prison code that stays with a certain brand of ex-con long after they’re released. Hathaway is such a con: determined, resolute, and devoted to his own Robin Hood brand of hacking ethics.

The film’s first half begins slow, with officials looking at computer screens of endless computer code and discussing IP addresses, elaborate encryptions, and hidden agendas, which is all quite dull and occasionally meaningless for the viewer. To augment these scenes, Mann incorporates sequences that take us inside the hardware to see a metropolis of grayscale circuit boards flashing with white electrical impulses, an altogether underwhelming visual experience already explored in The Matrix. Mann’s attention to detail does him a disservice through this visualization, but the second half pays off when the investigation gets closer to the source (globe-trotting between locations in Hong Kong, Los Angeles, Kuala Lumpur, and Jakarta), and several intense shootouts and chases ensue. Meanwhile, Tang plays the network engineer sister of Leehom’s investigator character, and she quickly falls for Hathaway’s severe presence in a convincing, if occasionally corny romance subplot.

Shooting in sometimes shaky digital photography, cinematographer Stuart Dryburgh renders a frenetic style, putting us into the moment when the film’s events start to pick up in the second half. Mann has been shooting on digital since before his breakthrough use of the medium on Collateral (2004), where he rendered one dark night in Los Angeles with unusual clarity. Lesser examples include his brief uses of digital on Ali (2001) and the gritty Miami Vice (2006), and then his mishandled use of the format on Public Enemies (2009). In Blackhat, the digital look brings a forceful realism to two shootout sequences, whose outcomes are shocking and move the plot into new directions. And while the shootouts here may not approach the unrivaled one in Heat, Mann’s sense of realism, and his authentic sound editing of deafening gunfire, places us into the moment, unable to escape. The director creates an incredible sense of danger in these scenes, whereas Mann’s megalomaniacal villain, and his overcomplicated scheme, is disappointing once it’s all revealed and rather quickly disposed of.

Though it begins as a cyber-crime procedural, Blackhat aligns with his earlier work by establishing a singular character operating by his own code, both literally and metaphorically. Hathaway becomes a fascinating Mann anti-hero because he excels in both the virtual world and the physical, and Hemsworth’s sheer physicality makes it credible. But it takes much of the film before the viewer realizes this, and it’s only after the cyber-terrorist is revealed to be something else, more akin to the so-called terrorists in Die Hard, that the structure and purpose of the film can be appreciated as a new entry in the director’s body of work about thieves and criminals, instead of a geopolitical story about cyber-terrorism (released just weeks after Sony’s cyber-scandal no less). Because of this, Blackhat will undoubtedly improve on future viewings for Mann devotees, whereas first-time viewers may be entertained but not wowed. The film is best in its tangible moments between characters, whether those moments involve realistic violence, intimate romance, or characters brooding in solemn singularity, all of which are dependable tropes in Mann’s engaging brand of cinema.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review