BlackBerry

By Brian Eggert |

Note: This review was originally published for the 2023 Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival and has been expanded.

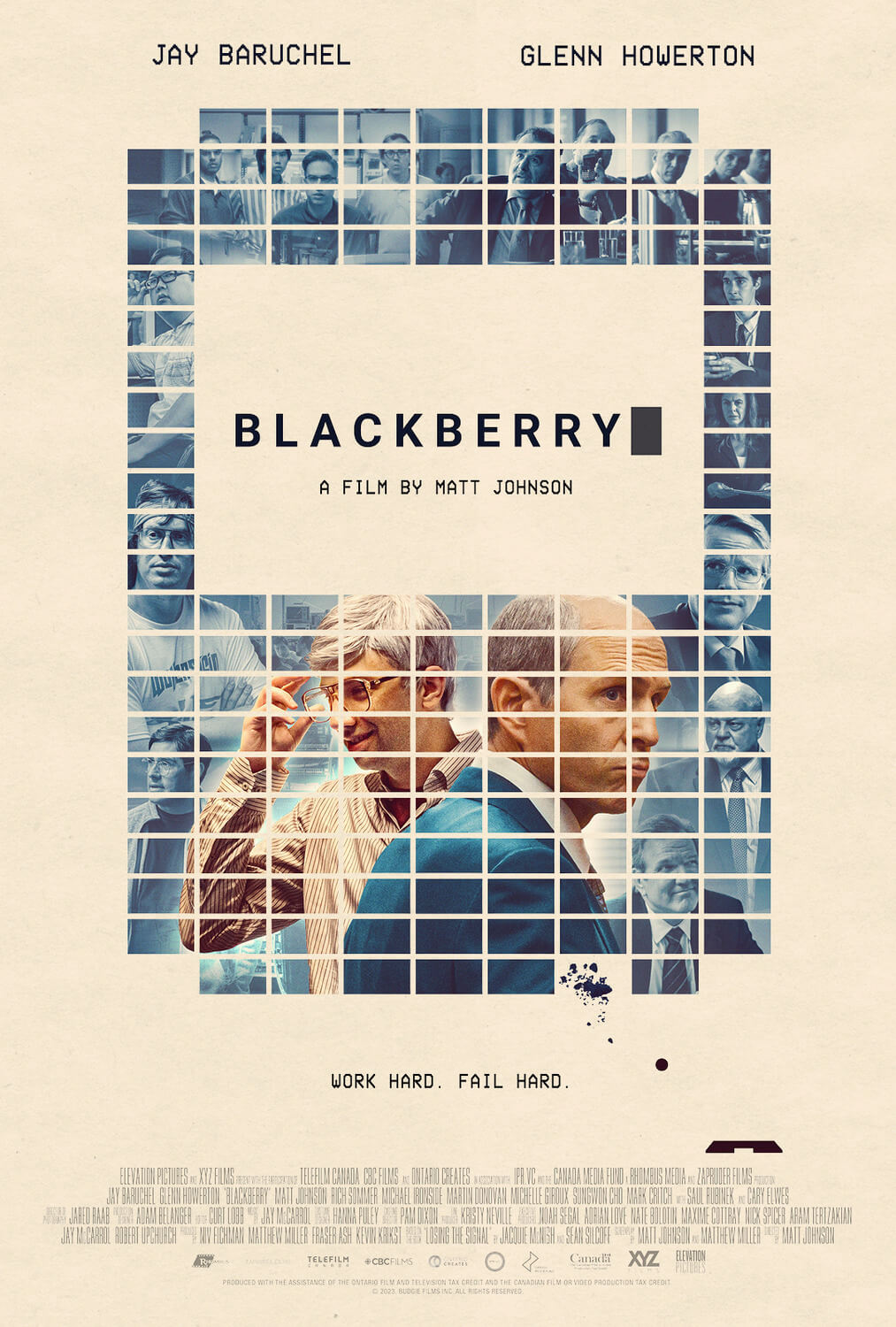

At the height of its popularity in the late 2000s, BlackBerry controlled over 50% of the US smartphone market and 20% of the global market—a demand they practically invented. With its signature clicking keypad, the device was so popular that it earned the nickname “CrackBerry.” But just six years after Steve Jobs announced Apple’s first iPhone in 2007, BlackBerry controlled 0% market share and gave up on producing smartphones altogether. Today, the name may not even register for younger generations, even though it seemed ubiquitous in the corporate arena during its heyday. So what the heck happened? Given its rise and fall, the BlackBerry and its creators at the Canadian software company Research in Motion (RIM) make for a naturally dramatic story. In director Matt Johnson and his co-writer Matthew Miller’s film about the company, they craft an entertaining cautionary tale about business ineptitude, cutthroat practices, greed, and hubris. Modeled after The Social Network (2010) but consistently funny—with its equal measures of ironic and acidic humor—BlackBerry offers a welcome alternative to the self-gratifying brand biopics of 2023.

If you want to feel cynical about the effect of American capitalism on pop culture, look at this year’s new wave of movies about the origin stories of popular products. Tetris presented itself as a Cold War thriller about an ambitious businessman trying to make a deal to get a video game out of the Soviet Union. Ben Affleck’s Air told the story of Nike’s marketing team pitching Air Jordans to the pre-NBA rookie Michael Jordan. Next month, Flamin’ Hot will detail how a Frito Lay janitor turned Mexican heritage into a popular flavor. As if commercial cinema wasn’t already the dominant force in Hollywood, each example doubles as a promotional device for its billion-dollar brand. Films like these don’t need product placements because each movie is a commercial. Fortunately, BlackBerry avoids any such residue by being about a product that no longer exists. Therefore, you’re less likely to feel that you’ve just endured a two-hour infomercial for the featured product, which is how I felt after the other brand biopics mentioned (all of which I enjoyed to varying degrees).

Based on Jacquie McNish and Sean Silcoff’s 2015 book, Losing the Signal: The Untold Story Behind the Extraordinary Rise and Spectacular Fall of BlackBerry, Johnson and Miller’s script has a zippy, propulsive energy that underscores the homemade quality of the technology and the corrosive ambition that made it a success. Unfolding from 1996 to the mid-2000s, the story follows RIM founders—resident boy wonder and prematurely graying Mike Lazaridis (Jay Baruchel) and his goofball friend Douglas Fregin (Johnson)—who work out of a crummy office in Waterloo, Ontario, populated by distracted computer engineers. After failing to pitch their product (“A pager, a cell phone, and an e-mail machine all in one”) to potential investors, they reluctantly hire a volatile but knowing executive to guide them through a sea of pirates. Jim Balsillie (Glenn Howerton) uses his shrewd business acumen to ensure the RIM guys aren’t exploited and can finally produce their dream device. But through a series of shady decisions on Balsillie’s part and Lazaridis’ later compromises, their product goes from a cutting-edge commodity to an inadequate competitor of the iPhone.

Shot by Johnson’s regular cinematographer Jared Raab, BlackBerry adopts a style of documentary realism, evoking the fast-paced aesthetic of Armando Iannucci’s In the Loop (2009). Raab often situates the camera as a rogue observer of the action, deploying hand-held setups and a shaky frame that reflects Lazaridis and Fregin’s disorganization, which requires them to hire Balsillie. Using punctuated zooms reminiscent of TV’s The Office, Johnson’s style is familiar but thoughtfully applied, showing the RIM crew as a bunch of screw-offs who thrive under work-hard, play-hard conditions—their long hours equalized by at-work movie nights (They Live, Raiders of the Lost Ark, etc.) and prolonged Doom sessions. Visuals aside, BlackBerry isn’t a documentary and takes liberties. Johnson’s role as Fregin is surely exaggerated for comic effect, complete with a velcro wallet and an omnipresent headband, even when he’s wearing a suit (I couldn’t find any images online of the real Fregin in a headband). This energy is supported by Jay McCarrol’s playful electronic score and a soundtrack of punchy and nostalgic tunes—but not the distracting array of wall-to-wall greatest hits heard in Tetris and Air.

Shot by Johnson’s regular cinematographer Jared Raab, BlackBerry adopts a style of documentary realism, evoking the fast-paced aesthetic of Armando Iannucci’s In the Loop (2009). Raab often situates the camera as a rogue observer of the action, deploying hand-held setups and a shaky frame that reflects Lazaridis and Fregin’s disorganization, which requires them to hire Balsillie. Using punctuated zooms reminiscent of TV’s The Office, Johnson’s style is familiar but thoughtfully applied, showing the RIM crew as a bunch of screw-offs who thrive under work-hard, play-hard conditions—their long hours equalized by at-work movie nights (They Live, Raiders of the Lost Ark, etc.) and prolonged Doom sessions. Visuals aside, BlackBerry isn’t a documentary and takes liberties. Johnson’s role as Fregin is surely exaggerated for comic effect, complete with a velcro wallet and an omnipresent headband, even when he’s wearing a suit (I couldn’t find any images online of the real Fregin in a headband). This energy is supported by Jay McCarrol’s playful electronic score and a soundtrack of punchy and nostalgic tunes—but not the distracting array of wall-to-wall greatest hits heard in Tetris and Air.

What works so well about BlackBerry are the clear personalities on display. Baruchel is terrific at conveying Lazaridis’ inner conflict between wanting to be kind and wanting to make his business thrive, and he remains sympathetic despite his later delusions of grandeur. Some combination of greed and naïveté left Lazaridis in ruination, along with his knack for technology but not business or people. Despite early victories, it hurts to watch him under pressure later, making one bad decision after another. Balsillie is comically ruthless at first, like a character out of Glengarry Glen Ross (1992) whose colorful berating of the RIM staff proves amusing—that is, until his shouting, swearing, and bullying become reckless (of course, they always were). Lazaridis looks up to Balsillie as a shark who’s capable of cutting through Gordon Gekko types with lines like “Perfect is the enemy of good.” And Lazaridis should have always followed his gut that “Good enough is the enemy of humanity.” Howerton, best known for It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, is superb in a role that shows his range. Meanwhile, Johnson’s Fregin is a constant source of humor as a pop-culture reference machine, but he’s also the heart of the story—an overgrown child who recognizes that work should be fun, and when it isn’t, the product suffers.

BlackBerry is often riotous in its small moments, such as Lazaridis coming down with hiccups during a business presentation. The script, as you will discover afterward, is also very quotable. But the lesson in the finale, where Lazaridis compromises his idealistic (but not wrong) quality control guidelines and, further, demonstrates his inability to understand an evolving marketplace, is awfully tragic. Of course, Lazaridis and especially Fregin ended up filthy rich, despite the product’s downfall. But the film isn’t about the status of their bank accounts today; it’s about the shattering of friendships and personal downturns. While all of these brand biopics have an underdog quality to them, only Johnson’s film has a handmade appeal, reminding us that these people started from nothing, made millions, and then faded into obscurity—leaving only a vague memory of “that phone that people had before they bought an iPhone.” BlackBerry is a surprisingly moving and compelling story, even more so than its recent counterparts, given the dramatic highs and subsequent lows on display. Its lessons feel honest because, sadly, more businesses collapse from similar mistakes than those that last or become billion-dollar enterprises.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review