Black Swan

By Brian Eggert |

Darren Aronofsky’s tragic psychodrama Black Swan puts ballet onto a dark stage of obsession and shocking imagery. Laced with overtones of sexual repression, paranoia, and body horror, this adult fairy tale comes rich with metaphors that are easily read but no less impactful for their straightforwardness. Though it resists clear exposition, the narrative unfolds with twists and turns that are sometimes predictable yet always dramatically significant. Made with all the bold visual style and narrative daring that one expects from Aronofsky, it proves to be his most ambitious and emotionally satisfying film thus far.

The film marks a step forward in Aronofsky’s career, employing his powerful sense of the visual from Requiem for a Dream and The Fountain, and he combines that with the dramatic consequence of The Wrestler. The result feels like something between Powell and Pressburger’s The Red Shoes and Roman Polanski’s Repulsion, in that the film presents a backstage ballet melodrama that takes place within the twisted psyche of the protagonist. Our perspective is that of a lead dancer whose sanity quickly comes into question, as her connection to her dancing drives her to evident hallucinations, which become more obvious, more visceral, and more dangerous as her psychological transformation manifests.

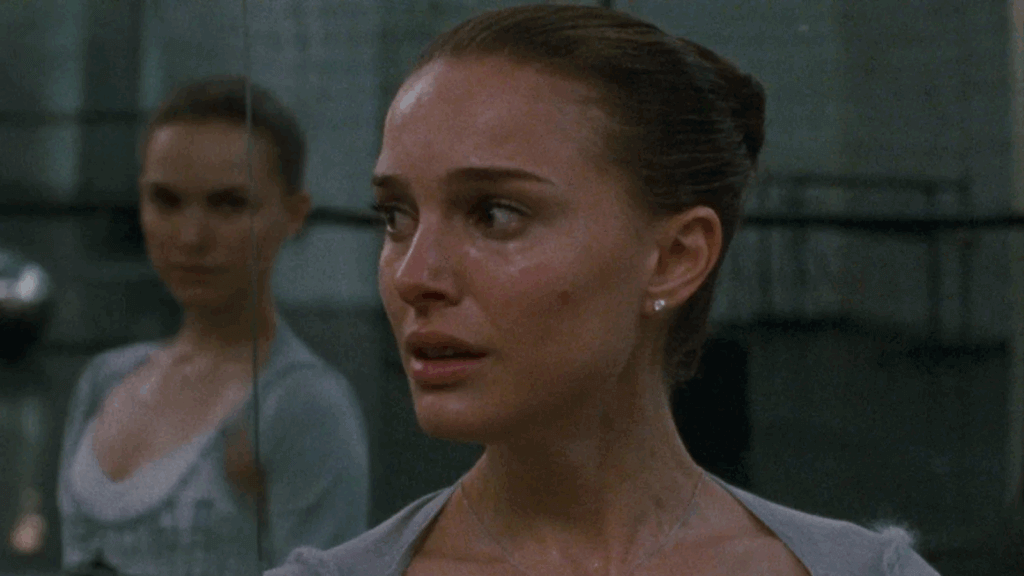

Natalie Portman gives an incredible performance as Nina Sayers, a young ballerina struggling for perfection to appease her company’s impresario, Thomas Leroy (the splendid Vincent Cassel). Nina wins the lead role of the Swan Queen in Leroy’s new production of Swan Lake with her technical skill, which makes her ideal for the innocent White Swan role, but she lacks the sensuality and spontaneity of the role’s alter-ego, the Black Swan. Leroy attempts to release Nina’s passions so that she might unlock her repressed sexuality and channel it into her performance, but she remains difficult to coax. And so, Nina grows obsessed with the idea that Leroy will select someone else from the company to replace her, such as Lily (Mila Kunis), whose grasp of sexuality seems effortless in comparison.

At home, Nina’s domineering mother (Barbara Hershey) treats her like a fragile child who will break under too much pressure, hinting at past psychological problems that would make Nina incapable of being on her own. Filled with stuffed animals and a pink color scheme, Nina’s room shows evidence that her mother has sheltered her, and maybe rightfully so. Scratches appear on Nina’s back, broken skin on her fingers, and bumps under her skin that may be black feathers emerging from within—as though she was literally becoming her part. Some of these physical signs are imagined, while others are not. As she grows further into her role, Nina’s paranoia takes over, and she anticipates betrayal at every turn, thrusting herself into violent, even self-destructive resolutions. But since everything we see comes from Nina’s perspective, we cannot trust our eyes; rather, we must trust only how the film cleverly links us with Nina’s mental state, unstable and unsettling though it may be.

Aronofsky shoots almost exclusively with handheld cameras in intimate close-ups that force a connection between the viewer and the film’s characters. This approach heightens the emotional response but places a distance between the viewer and our appreciation of the technical dancing. Only a few wide shots allow us to appreciate the ballet sequences themselves in their entirety, as Aronofsky prefers keeping the frame tight on his protagonist’s expressions, her emotions reeling as the camera rotates around her. Much of the “action” occurs on Portman’s face, her every gesture revealing another insecurity or fear. In some ways, Aronofsky’s choice to employ so many close-ups was wise, in that the connection between Nina and the audience remains undeniable, almost tangible. He uses several shots of mirror reflections, suggesting Nina’s increasing duality and fragmentation. Still, the viewer never gathers an appreciation for the beauty of dance, the artistry, or the physical grace and toils behind it. More close-ups show us Nina’s open wounds, some made through dance, yet Aronofsky fails to develop in the viewer an appreciation for the artform.

Given these choices, Black Swan becomes more about Nina’s crumbling psychology than dance, whereas it is dance that propels her to such extreme behavior. It would seem crucial that we understand both. What’s more, Portman trained for months to learn ballet, so few dance doubles were needed during shooting. Although the viewer can hardly take full notice of Portman’s efforts because Aronofsky so rarely pulls back for a panoramic view of the ballet sequences. These are mere preferences from a formal perspective, however, and hold little bearing on the impact of the film from an emotional standpoint, which by the conclusion sweeps the viewer away with its potent metaphors and crushing last scene.

The film makes an obvious companion piece to Aronofsky’s last release, The Wrestler, which offered a character study through the backdrop of professional wrestling. Shot in a similar grainy, really there style, both films fall on performers who punish themselves through their art—though wrestling is surely the “low art” to ballet’s “high art”. More sophisticated and intricate than that film, Black Swan warrants a profound response both from its stark melodramatic turns and from the sheer authority behind its artistic ambitions. This is an impressive work that may lack the affection that The Red Shoes has for dance, but through its confronting visual intensity never fails to be evocative.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review