Black Panther

By Brian Eggert |

Black Panther marks the first entry in the Marvel Cinematic Universe not about a white male. After seventeen titles, the MCU has finally ventured outside of its limited racial boundaries, centering on a superhero who is neither white nor Western. (The first Marvel Studios feature with a female hero, Captain Marvel, will debut next year.) The studios’ baby steps toward multiculturalism reflect a growing demand for diversity among superheroes, as enthusiasm for last year’s Wonder Woman proved. And while the film’s representation of African characters remains unique within the confines of the MCU, its politics and moral complexity engage as no MCU film has before. Directed by Ryan Coogler, Black Panther does not reinvent the genre; the filmmaking and entertainment value adhere to the precepts of a Hollywood blockbuster. But Coogler introduces such a singular world with the fictional African country Wakanda, and the issues that emerge from its isolationism are vital in today’s culture war, where xenophobia and intolerance run rampant. By inserting such ideas into what might otherwise be a diverting tentpole, Coogler sets the film apart from other titles in the MCU, creating something smarter and more substantive than a typical superhero yarn. The film has something to say about race, history, and social revolution—ideas percolating at this moment in the United States and beyond.

Marvel Comics conceived the first African superhero in 1966, the same year the social revolutionaries of the Black Panther Party organized amid the Civil Rights movement in the United States. Ever striving for some measure of social justice, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby introduced Black Panther in the pages of Fantastic Four No. 52, followed by regular spots in The Avengers and the genre series Jungle Action over the coming decade. Lee and Kirby’s superheroes often contained commentaries on prejudice and inequality. For instance, their X-Men were a marginalized group of mutants hated by standard homo sapiens. Beating their DC Comics rivals to the punch, Marvel continued to develop Black characters for their readers, such as the Kenyan mutant Storm or the African American heroes Falcon and Luke Cage. Though many Black superheroes would emerge over the coming decades, it was not until the 1990s and 2000s that Black characters began to feel like regular fixtures rather than token inclusions.

Hollywood superheroes have progressed much slower than those in comic books. When Anthony Mackie’s Falcon does little more than support Captain America, and producer Kevin Feige seems hesitant to commit to a Black Widow feature, the MCU’s lack of diversity could hardly be described as progressive. Coogler’s film could demonstrate to Marvel, and its Disney overlords, that audiences want superhero stories featuring someone other than another white guy. Then again, New Line Cinema’s profitable Blade franchise should have confirmed as much. In fact, Blade himself, Wesley Snipes, endeavored for most of the 1990s to get a Black Panther film made with filmmakers like Mario Van Peebles and John Singleton. Later, Marvel courted Ava DuVernay (Selma, 13th) to direct. DuVernay passed, believing she would have to make too many artistic compromises—which was evidently not a concern for Coogler, whose Fruitvale Station (2013) and Creed (2015) were well-received by most. Whatever DuVernay’s concerns might’ve been, it’s difficult to imagine an MCU film with more political teeth than the one written by Coogler and Joe Robert Cole.

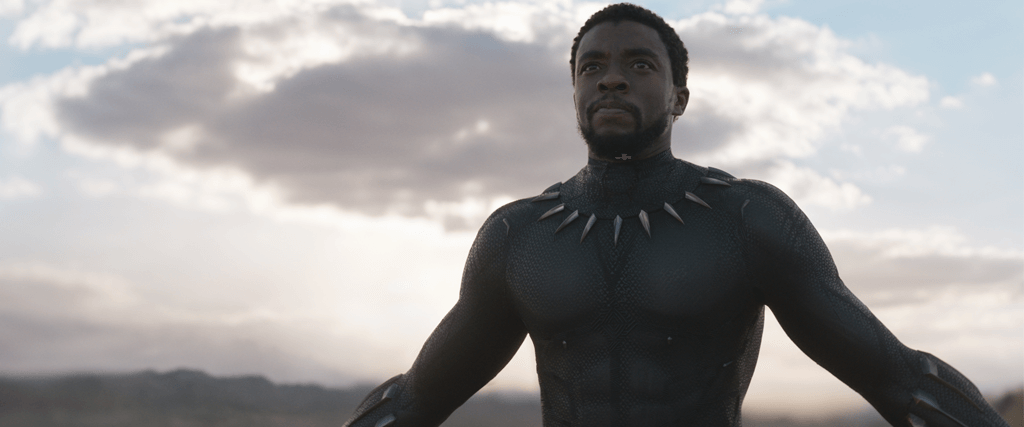

Chadwick Boseman, otherwise best known from the Jackie Robinson biopic 42 (2013), returns to the role he originated in Captain America: Civil War (2016), which took place just a week before the events in Black Panther. T’Challa, the new king of the reclusive African nation Wakanda, is crowned after his father (John Kani) was killed. He resolves to follow the long-upheld tradition of seclusion, maintaining a blind eye to the country’s real utopian identity. Though masquerading as a third world country, the technologically advanced Wakandan nation hides its futuristic gizmos from the world. Their past leaders have worried about letting refugees within their borders (sound familiar?), fearing that once the world knows about their tech—facilitated by Marvel’s most precious metal, vibranium—they will be targets. After all, vibranium has allowed the country to develop flying crafts that look like UFOs, medical treatments that can heal crippling wounds, and yes, a clawed black super-suit available only to Wakanda’s king.

Chadwick Boseman, otherwise best known from the Jackie Robinson biopic 42 (2013), returns to the role he originated in Captain America: Civil War (2016), which took place just a week before the events in Black Panther. T’Challa, the new king of the reclusive African nation Wakanda, is crowned after his father (John Kani) was killed. He resolves to follow the long-upheld tradition of seclusion, maintaining a blind eye to the country’s real utopian identity. Though masquerading as a third world country, the technologically advanced Wakandan nation hides its futuristic gizmos from the world. Their past leaders have worried about letting refugees within their borders (sound familiar?), fearing that once the world knows about their tech—facilitated by Marvel’s most precious metal, vibranium—they will be targets. After all, vibranium has allowed the country to develop flying crafts that look like UFOs, medical treatments that can heal crippling wounds, and yes, a clawed black super-suit available only to Wakanda’s king.

Wakanda is the heart of Black Panther. Exceptional world-building establishes its people as an advanced society and proud tribal nation. Jealously devoted to its customs, Wakandans talk about their country with an infectious allegiance to its policies and traditions. Early in the film’s admittedly slow start, T’Challa must drink a potion that neutralizes his Black Panther powers to take part in an open challenge to the throne. Should he lose, his people would lament his loss but willingly would follow a new leader. As a ruler, T’Challa worries whether he will live up to the example of his father (John Kani), leading to existential, soul-searching meetings in the astral plane reminiscent of The Lion King. Despite their power and pride, their government’s Wakanda-first policy bars any refugees from entering their borders, and they dub white men, such as Martin Freeman’s CIA agent Ross, as “colonizers.” Indeed, the Wakandans have watched through history as other cultures have subjugated Africans in acts of colonization, slavery, and mass genocide, and they have resolved to protect their own.

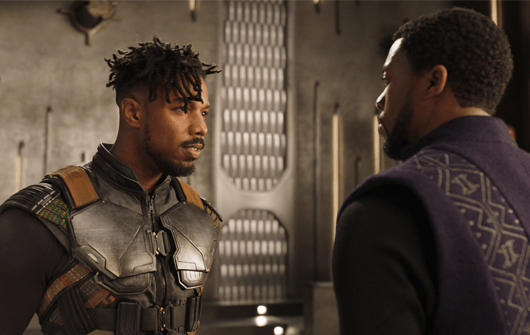

As for the superhero conflict, the best villains are the ones you can understand, empathize with, and perhaps, to some extent, even agree with. The X-Men’s nemesis Magneto made sense because he believed in evolution and natural selection; if threatened by an intolerant society, the more powerful mutants should fight back, he believed. Similarly, Michael B. Jordan (star of both Coogler’s other films) plays Killmonger, a silly name for a character harboring legitimate rage over centuries of dehumanizing crimes committed against people of color, from the CIA injecting drugs into Los Angeles neighborhoods to the assassination of vocal Black leaders. Killmonger, whose history reveals a scandal in T’Challa’s family past, wants the Wakandan throne to liberate the world’s “2 billion people who look like us,” he tells his followers. His Master Plan involves distributing advanced Wakandan weaponry for a worldwide takeover; even so, the nature of the threat is a reaction to the history of subjugation and oppression. Best of all, Killmonger challenges T’Challa in a way that goes beyond CGI battles; he forces our hero to reconsider his position and admit his failings. And while Killmonger doesn’t single-handedly solve the MCU’s problem of dull villains, he’s the reason Black Panther gives the audience much to think about long after the standard post-post-credits scene.

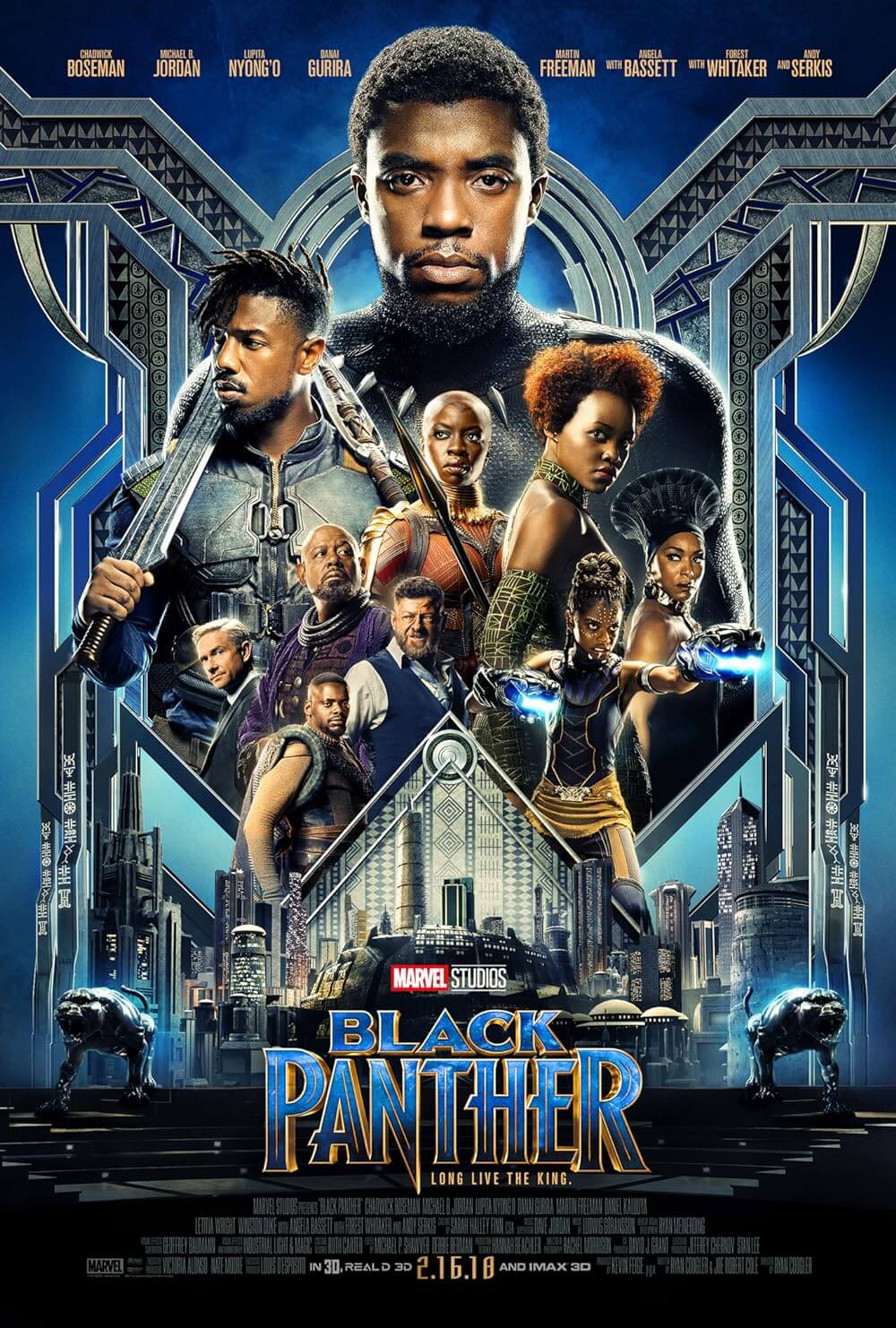

The male-centric conflict between T’Challa and Killmonger aside, this is a film populated by a superb supporting cast, most of them strong women. Danai Gurira might steal the show as General Okoye, sworn guardian of the throne. A regular fixture on AMC’s The Walking Dead, Gurira once again demonstrates her capacity to play a weapon-wielding badass, and here she manages moments of begrudging humor. Lupita Nyong’o plays Nakia, a Wakandan spy, and T’Challa’s lingering love interest. When T’Challa, General Okoye, and Nakia take a short trip to South Korea to capture the criminal Ulysses Klaue (Andy Serkis), the trio has a playful albeit short-lived dynamic that brings the characters to life. Angela Bassett is dependable as ever as T’Challa’s mother Ramonda. Letitia Wright also shines in her scenes as Shuri, T’Challa’s sister and Wakanda’s tech wiz—ostensibly the Q to Black Panther’s James Bond. A comic relief character, Shuri nonetheless adds to the endearing quality of the film’s main character. Wright’s scenes with Boseman lend the hero his few moments of levity. To be sure, if there’s a weak component in the cast, it’s Boseman, whose role confines him to humorless and joyless nobility. The fault is not Boseman’s per se; the script doesn’t give T’Chall much personality or a compelling arc. He’s saddled with the usual self-doubts of young royalty, where questions about whether he’ll live up to his father’s legacy, or whether his father’s legacy deserves to be upheld, saturate his mind. Forest Whitaker and Get Out‘s Daniel Kaluuya also appear, making the most out of their sizeable supporting roles.

The male-centric conflict between T’Challa and Killmonger aside, this is a film populated by a superb supporting cast, most of them strong women. Danai Gurira might steal the show as General Okoye, sworn guardian of the throne. A regular fixture on AMC’s The Walking Dead, Gurira once again demonstrates her capacity to play a weapon-wielding badass, and here she manages moments of begrudging humor. Lupita Nyong’o plays Nakia, a Wakandan spy, and T’Challa’s lingering love interest. When T’Challa, General Okoye, and Nakia take a short trip to South Korea to capture the criminal Ulysses Klaue (Andy Serkis), the trio has a playful albeit short-lived dynamic that brings the characters to life. Angela Bassett is dependable as ever as T’Challa’s mother Ramonda. Letitia Wright also shines in her scenes as Shuri, T’Challa’s sister and Wakanda’s tech wiz—ostensibly the Q to Black Panther’s James Bond. A comic relief character, Shuri nonetheless adds to the endearing quality of the film’s main character. Wright’s scenes with Boseman lend the hero his few moments of levity. To be sure, if there’s a weak component in the cast, it’s Boseman, whose role confines him to humorless and joyless nobility. The fault is not Boseman’s per se; the script doesn’t give T’Chall much personality or a compelling arc. He’s saddled with the usual self-doubts of young royalty, where questions about whether he’ll live up to his father’s legacy, or whether his father’s legacy deserves to be upheld, saturate his mind. Forest Whitaker and Get Out‘s Daniel Kaluuya also appear, making the most out of their sizeable supporting roles.

Elsewhere, Coogler’s direction has less personality or distinction than his previous work. He adopts that homogenized MCU house style, enforced by the studio to assure a consistent feel across multiple mini-franchises—a style only a couple Marvel directors have been able to innovate upon (Taika Waititi and James Gunn, for example). He incorporates a few impressive extended takes, obviously comprised of several shorter takes digitally woven together to create the illusion of a longer shot, but no less effective as an immersive approach to scenes of hand-to-hand combat. Director of photography Rachel Morrison, recently Oscar-nominated for her work on Mudbound last year, captures dissimilar settings with equal beauty: the grittiness of a Los Angeles street scene; the neon glow of a dazzling South Korean car chase; the luminescent sunsets in Wakanda. Coogler and Morrison seem to have watched Skyfall as a point of reference, as Black Panther reaches for that actioner’s variety of locations and visual styles. Of course, there’s also a digital sheen to many scenes in Wakanda, as computers have brought this world to life. The underground climax in the vibranium core looks particularly cartoonish, or at least on par with several other climactic MCU battles. (Additionally, whoever was in charge of continuity for the length of Boseman’s beard wasn’t doing their job; his beard length distractingly alternates from a thick tuft to a tighter cut throughout the film.)

Regardless of Black Panther‘s average formal presentation that aligns with the larger MCU, Coogler and Cole’s excellent script is what makes the material potent. The film has an unabashed and defiant political viewpoint, supplementing its superhero genre mechanics with a relevant commentary on history, racism, and human injustice, which is more than can be said of earlier MCU titles. When T’Challa reminds us “The wise build bridges, while the foolish build barriers,” or declares, “All of you were wrong to turn your backs on the rest of the world,” the jabs at the Trump administration are evident, and the film’s political position becomes unambiguous. Black Panther calls for active participation in the human race beyond the illusion of borders, skin color, religion, or nationality. It explores and understands the appeal of tribalism, but then asks people to broaden their narrow views and realize we’re all part of the same tribe. Coogler’s ability to provide rousing superhero escapism that also taps into the zeitgeist makes his film an immersive piece of entertainment for the times.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review