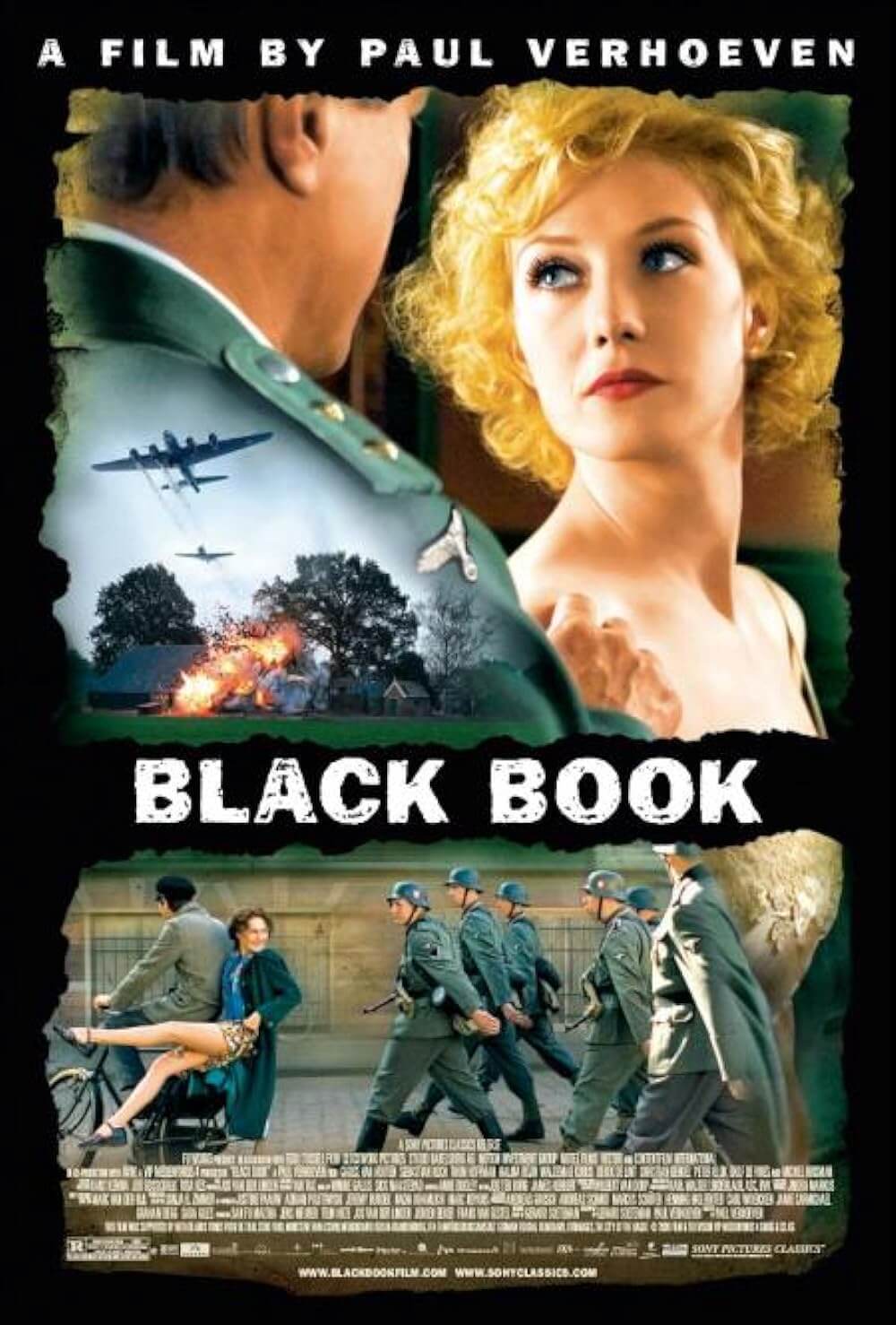

Black Book

By Brian Eggert |

In the early 1940s, director Paul Verhoeven was just a boy, and his family lived in the Nazi-occupied Netherlandish city of The Hague. With his home near a German military base, his childhood became riddled with grisly sights and ever-present peril—dead bodies and war atrocities everywhere. Unlike most children, the war’s adventurous aspects fascinated young Verhoeven, but they also terrified him. These inescapable terrors were burned into, perhaps even exaggerated by, his childhood mind, and later served as his influence on potently realistic depictions of bloody violence and war commentary. With films like Soldier of Orange, RoboCop, Total Recall, and Starship Troopers, Verhoeven embraces themes of wartime espionage, brutality, and totalitarianism, often with a dash of satire. His unique perspective and undeniable vision have made him a Hollywood hit, while Verhoeven’s last film, 2000’s disappointing Hollow Man, left a sour taste in the collective mouth of his fans.

With his new picture, Black Book (Zwartboek), the Dutch filmmaker returns to his home to skillfully constructed cinema, the likes of which he’s not made for more than a decade. The story begins toward the end of WWII, a setting from which Verhoeven channels imagery from his childhood. His female hero is Jewish singer Rachel Stein (Carice van Houten, who gives a staggeringly good performance), who hides from Nazi forces, veiled in the home of a Christian family inside the Netherlands. When her cover is literally blown, she comes into contact with the Dutch resistance, which offers to get her over the border on a boat. Consulting her family attorney, she takes a bundle of money and prepares for departure, only to find her parents and brother will be on the same boat with a small crowd of wealthy Jews who could afford to pay for their risky escape.

When the escape attempt tragically fails, fate propels her into working with a Dutch resistance group. Given a new name, Ellis de Vries, Rachel’s first major assignment is to play fiancée to Hans Akkermans (Thom Hoffman) while transporting illegal goods. During the mission, she finds herself acting German to avoid Nazi officers who are checking bags on a train. She inconspicuously hides in the compartment of a German SD officer Ludwig Müntze (Sebastian Koch), whom she tempts with her feminine charm. Later, Rachel’s resistance group asks her to infiltrate the SD office in The Hague to get information on some captured associates by seducing Müntze. She asks the resistance leaders if this means they want her to “screw” him—she wants everything to be clear—and they ask her what she’s willing to do. She agrees to the job, saying she’ll go as far as Müntze wants to go.

Her seduction in full swing, Rachel begins to fall for Müntze; after he discovers Rachel is a Jew, he curiously maintains the affair, not caring about her heritage. Though a Nazi, Müntze risks his life by negotiating with members of the Dutch resistance, hoping to save lives on both sides. As sympathetic as Claude Rains in Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious, Müntze is not your typical Sieg Heil-shouting Nazi. On the one hand, he does something meekly human like collecting stamps; on the other, his stamps are collected from countries occupied by Nazi Germany. Morally ambiguous characters like this fill Black Book; each follows their own sense of justice and revenge and their own ideas on how to survive in wartime. We might begin to think Rachel falling in love with Müntze makes her a hypocrite, but then we learn that no one in Verhoeven’s wonderfully difficult film is who we think they are. By depicting the ugliness of war, specifically the depths to which war allows human depravity to sink, Verhoeven underlines with blood the horrors our civilization permits due to humanity’s equivocal fallibility.

Her seduction in full swing, Rachel begins to fall for Müntze; after he discovers Rachel is a Jew, he curiously maintains the affair, not caring about her heritage. Though a Nazi, Müntze risks his life by negotiating with members of the Dutch resistance, hoping to save lives on both sides. As sympathetic as Claude Rains in Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious, Müntze is not your typical Sieg Heil-shouting Nazi. On the one hand, he does something meekly human like collecting stamps; on the other, his stamps are collected from countries occupied by Nazi Germany. Morally ambiguous characters like this fill Black Book; each follows their own sense of justice and revenge and their own ideas on how to survive in wartime. We might begin to think Rachel falling in love with Müntze makes her a hypocrite, but then we learn that no one in Verhoeven’s wonderfully difficult film is who we think they are. By depicting the ugliness of war, specifically the depths to which war allows human depravity to sink, Verhoeven underlines with blood the horrors our civilization permits due to humanity’s equivocal fallibility.

Comparable to 1940s wartime espionage thrillers such as Passage to Marseille, Uncertain Glory, or even To Be or Not to Be, Verhoeven uses the underbelly of WWII as a playground for entertainment, even the ghastliest of horrors. The director worked on this script for more than fifteen years, wanting to tell the story of Dutch resistance fighters, but only recently changed the main character into a woman. The result changes the story, and in Verhoeven’s mind, completes it. With Rachel selling herself to the idea of resistance, she becomes another victim of war, only her suffering transpires without violence; instead, she is ripped apart by her own desperation to stay alive. Which isn’t to say this picture avoids violence. It’s a Paul Verhoeven film, after all. This is the director behind Robocop and Total Recall, films so bloody they initially received X-ratings. Each splattering impact from a bullet or white-knuckle blow from a fist in Black Book looks exceptionally painful (a director trademark), though the visceral quality is part of Verhoeven’s sensationalism as an entertainer.

A side-effect of growing up around violence as a child, Verhoeven represents brutality more viscerally and realistic than any other filmmaker; he never lingers on the appalling violence, but there’s always a sudden barrage of bullets around the corner to jolt his unsuspecting audience. Nevertheless, when we see Rachel sacrificing her own body and sexuality to Müntze for the first time, no splash of blood can evoke the audience’s sense of repulsion. Each day when she goes to work at Nazi headquarters, playing Nazi secretary almost too well, she swallows whatever Jewish pride she might have retained for the cause. We never question her motives, but her resistance friends do. Her capability to do whatever is necessary to keep the right secrets hidden and expose the wrong ones, even when her punishment becomes grotesquely humiliating, proves her intentions… But that doesn’t necessarily mean she’s a good person. Rachel dances somewhere on the line between heroine and femme fatale.

Verhoeven cleverly avoids conventional wartime good-guy vs. bad-guy storytelling; he takes the same stance as Steven Soderbergh did with The Good German—asserting that war makes people do things that may not be correct or righteous, but are compulsory to survival. After years of mediocre material, Black Book elevates director Paul Verhoeven away from his recent reputation for low-brow subject matter and back into a quality of filmmaking that contains gratifying sentiments just emerging from the blinds of an engrossing WWII thriller. There could hardly be a motion picture at once as thrilling and confronting as this one manages to be, and with Verhoeven’s penchant for intense violence, suspenseful action, and grotesque wartime horrors to boot. But the way it all works together makes this one of the best films of 2006, a film that entertains as much as it challenges us to think about what war does to people, the lows to which it makes them sink. It’s also Verhoeven’s most personal work of his career, and we can feel that in the way he has elevated the material and his craft to tell this story.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review