Birth

By Brian Eggert |

An unbroken tracking shot follows a lone jogger through Central Park in winter. Against this image, we hear the jogger’s voice answering questions after a lecture. He doesn’t believe in reincarnation, he explains. “If I lost my wife and the next day, a little bird landed on my windowsill, looked me right in the eye, and in plain English said, ‘Sean, it’s me, Anna. I’m back’ What could I say? I guess I’d believe her. Or I’d want to. I’d be stuck with a bird. But other than that, no. I’m a man of science. I just don’t believe that mumbo-jumbo.” Reverberating through us, Alexandre Desplat’s score carries the jogger along, the composer’s vast strings filling the simple image with deep foreboding and introspection. Almost as if we’re following the boy on his Big Wheel through the Overlook Hotel in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, the jogger makes his way through the park. Under a bridge along the path, he slows in the dark, and as he stops, his hands clutch his knees, and he topples over dead. In the very next shot of Birth, director Jonathan Glazer shows the water delivery of a baby boy, and again we’re reminded of a Kubrick film, this time the so-called Star Child from 2001: A Space Odyssey. As viewers, we must deliberate over these two scenes, which appear in sequence before the opening title.

How are the images connected, if at all? Has Glazer just implied the jogger’s reincarnation and therein realized an ironic transmigration, or is this merely how we wish to interpret seemingly unconnected images to offer ourselves an easier reading of death and life? Released in 2004 to accusations of pretentiousness and impenetrability, Birth is the second feature by British filmmaker Glazer, visualist director of Sexy Beast (2000) and several music videos by Radiohead and Massive Attack. Demonstrating a masterful control of his visual craft and narrative austerity, Glazer channels both the measured and intentional pacing of Kubrick and the surrealist observations on class of Luis Buñuel. Along with his screenwriters Jean-Claude Carrière and Milo Addica—the former a long-time collaborator with Buñuel, the latter a severe dramatic realist—Glazer conjures reactions of either loathing or a kind of hypnotic spell with his film. And its divisive quality was all but solidified by the story. A decade after the death in the opening shots, a 10-year-old boy appears before the jogger’s widow and claims to be her late husband reborn, and she begins to believe him, even contemplating running away with him.

Nicole Kidman gives an intensely nuanced performance as Anna, the widow of Sean, the jogger. After ten years, she has finally made plans to remarry and lives, along with her fiancé, Joseph (Danny Huston), in a chic apartment owned by her mother (Lauren Bacall) on New York’s Upper East Side. At her mother’s birthday party, a short-haired, round-faced boy (Cameron Bright) with a solemn expression enters the apartment unnoticed. Once the candles are blown out, he makes his presence known and insists that Anna should not remarry to Joseph. This would be strange and almost comical, except the unnerving boy, also named Sean, claims to be her reincarnated husband. Neither Anna nor Joseph finds the boy’s claims funny, Anna desperately clinging to memories of her Sean and Joseph eager for her to forget. Nevertheless, the decorum of these well-mannered socialites requires that they resolve this problem maturely, first speaking to the boy’s parents (Ted Levine, Cara Seymour) and then Anna’s doctor brother (Arliss Howard) to perform an interrogation. At each step, the young Sean offers information only Anna’s former husband could know, and she comes to believe the impossible.

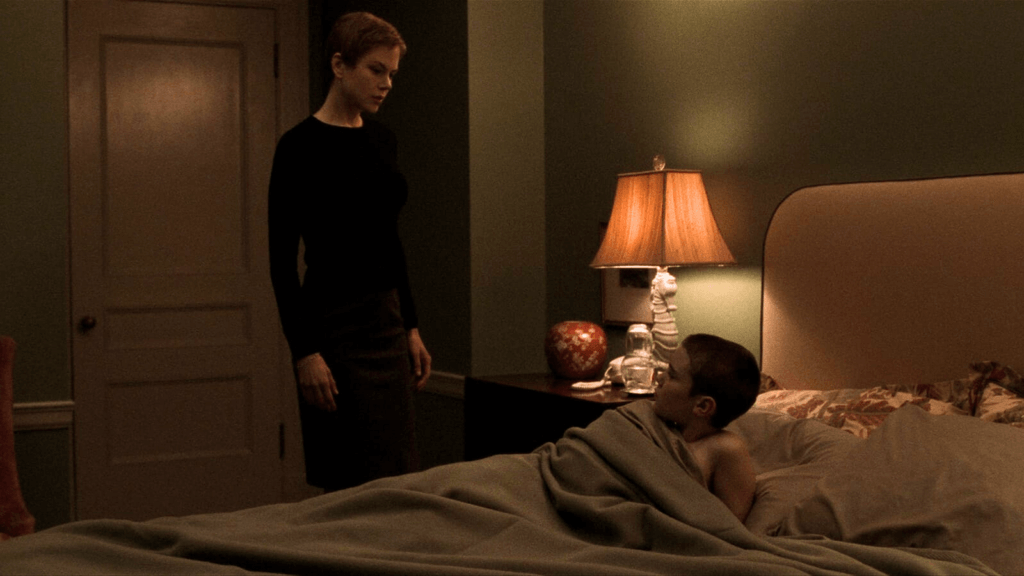

While Anna becomes progressively more convinced the boy is her husband, jealousy, over both the boy and the elder Sean, drives Joseph from bemused disbelief to a violent outburst. For everyone else but Anna, there are two possibilities: Either the boy is telling the truth or he’s lying, whatever his reasons may be for doing so. Sean’s answers to skeptics’ questions are short and ambiguous, containing just enough detail to remain convincing, or at least not offer a negative confirmation. Despite his inscrutable face and the beyond-his-years gravitas in his eyes, Sean also has very childlike moments eating ice cream and cake, swinging in a playground, or kicking Joseph’s chair at a pre-wedding ceremony. Bright’s face is an empty vessel where emotions are projected—both Anna’s and those of the viewer. The young actor, the same age as his character when Birth was in production, played a number of grave children (in Godsend and X-Men: The Last Stand), but he’s convincing as Sean because his behavior resists answers. His uncanny and off-putting presence, ghostly or otherwise, possesses Anna, not unlike Mia Farrow in Rosemary’s Baby, another film about a New York socialite swept up in possible supernatural circumstances. Even Kidman’s red, close-cropped hair emphasizes this correlation and her character’s emotional state under heightened circumstances. More is drawn from Kidman, whose face contains a wellspring of loneliness, desire, heartbreak, and possibility all at once in a scene at the opera, another long, unbroken shot by Glazer as the frame slowly zooms on Kidman’s searching expression.

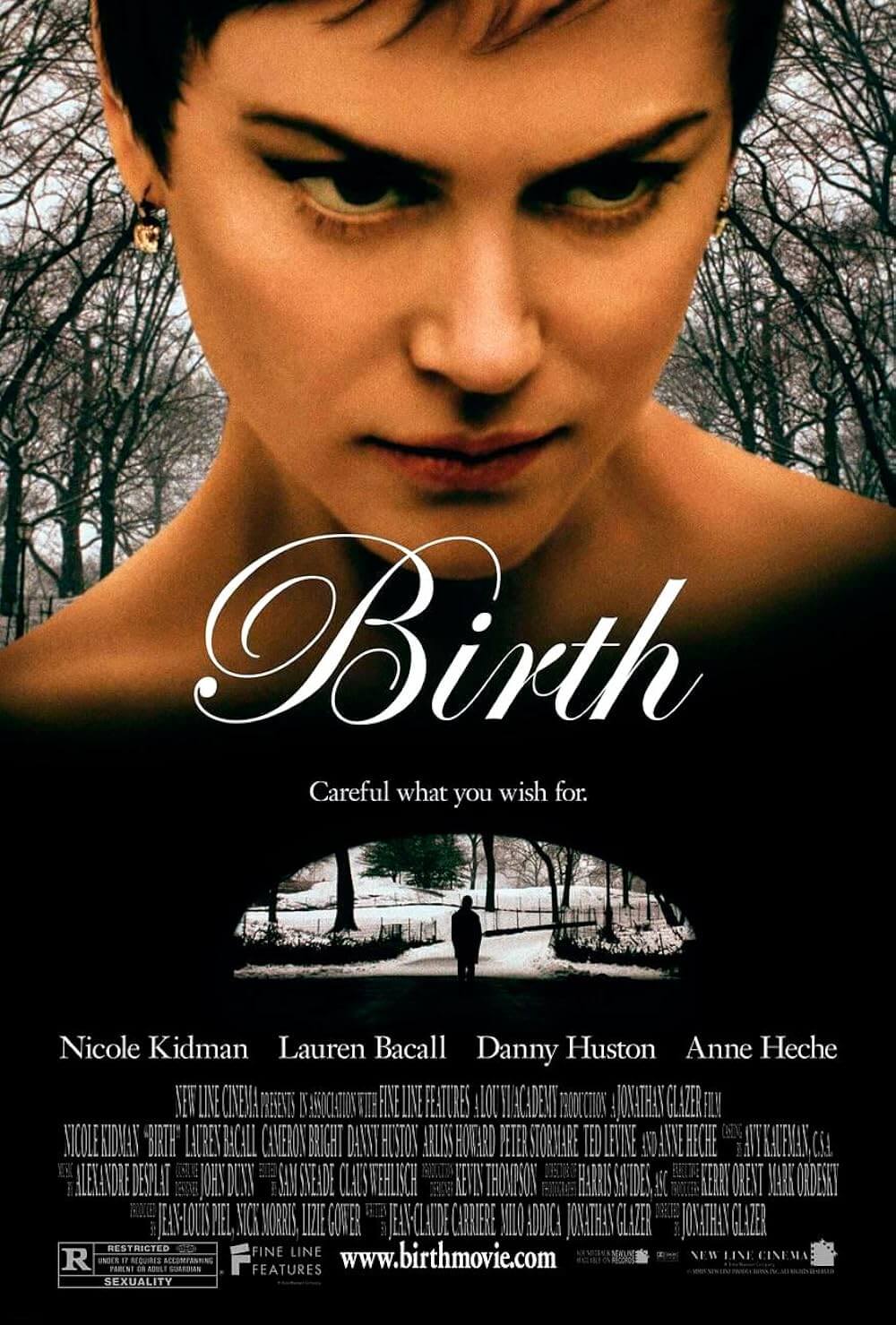

Upon the film’s release after its polarizing debut at the Venice Film Festival, critics interpreted Birth as a supernatural thriller or horror movie. In those terms, Glazer’s film admittedly failed (not that Glazer ever intended his film to be thrilling). Ray Bennet from the Hollywood Reporter claimed, “It has no suspense because it has no belief in itself.” After seeing the film, it’s any wonder how someone could view it as a proposed thriller, given its arthouse pacing and the European-styled elegance pervading throughout. The marketing department at the distributor, New Line Cinema, didn’t help disaffirm this, their poster reading “Careful what you wish for” in an ominous tone under Kidman’s enlarged and wary-expressed face. Other critics didn’t know what they were watching. “All I could think,” wrote Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly, “was ‘What in God’s name do the filmmakers think they’re doing?’” These views were compounded by some controversy around the scenes involving Anna and the young Sean, as the film shows Kidman kissing and, albeit tastefully shot, taking a bath with Bright. But Glazer resists taking the scenes between these two actors too far, relying on a sense of uncomforting connection and resistance toward the idea that the young Sean is Anna’s husband. In the tub, Anna asks him what he’s doing. He responds coolly, “I’m looking at my wife.”

All the misinterpretation and second-guessing about Birth and what it was supposed to be disappears when the viewer considers the elements onscreen, which are not those of a thriller but rather a ponderous drama about coping (or not) with death. Repeated viewings only strengthen the film’s emotional resonance once we accept the ending, and the mysteries present throughout the picture are no longer mysteries but clues into Anna’s mental state. As Anna talks about running away with the boy until he comes of age, the film gradually reveals how the boy came to learn about Anna’s husband. A family friend, Clara (Anne Heche), explains that she was Sean’s lover and, because Sean preferred her to Anna, Sean gave letters to her, which Anna wrote to Sean. But Sean never opened these private letters and, as a gift to Clara, they were proof that he loved her more than his wife. Avoiding an impulse to give Anna the letters upon her engagement to Joseph, Clara buried the letters in the park, and the boy Sean witnessed this. Unearthing them, he learned about Anna and, in an almost trancelike state once he consumed himself with the letters, imprinted onto Anna. Once we discover the boy is a fraud, the film’s timbre shifts to Anna and her unwillingness to move on from her late husband. Although she doesn’t know the extent to which she was deceived—she doesn’t learn about Clara and Sean’s affair—she cannot marry Joseph as Sean’s presence, real or not, still lives inside of her.

Glazer’s brooding treatment dances on the unearthly boundary between surrealism and melodrama, where each scene belongs either in a Buñuel film, a Kubrick film, or that of Ingmar Bergman. Cinematographer Harris Savides demonstrates meticulous control over the frame in long-held pensive shots, fluid camera movements, and extended Kubrickian zooms, while production designer Kevin Thompson finds and creates lavish but icy apartment interiors in which this chamber drama unfolds. Glazer’s entire production is elegant and, in a way, restrained from pure expression, while Desplat’s discordant music strikes suspicious sounds echoing both the film’s operatic and mysterious qualities.

Indeed, in watching Birth, the viewer can easily lose themselves in the technical perfection of the filmmaking. But there’s an astute narrative treatment as well; Glazer’s style seems hesitant to define Kidman’s character and leaves Bright’s a mystery, but he does this, as with the opening scenes, to allow the viewer to make connections and assumptions on their own. The cold New York socialites like Anna’s mother or Joseph see the boy as a fraud because all they see is a child (Anna’s mother jokingly calls the boy “Mr. Reincarnation” and later admits to him, “I never liked Sean,” referring to her daughter’s former husband in the third person to denote she doesn’t believe the boy’s claims). Anna sees possibility in the boy, but Glazer doesn’t push his audience too far in either direction. In his elusive and spellbinding approach, Glazer succumbs to the possibility of his film’s premise.

More than the mystery of its basic foundation, however, Birth represents a disquieting examination of how a profound loss can affect someone and leave them desperate for solace, searching for answers in ethereal places of spirituality and reincarnation, where answers are elusive and easier to accept because we invent them. Some analyses of the film have even suggested the spirit of Anna’s husband took over the boy for a time, although no significant evidence in the film supports this theory beyond the boy’s sudden collapse in one scene or his knowledge of where the jogger died. That such a reading occurs after the boy’s grand lie is revealed remains a testament to people’s need for something more than the bitter reality of death. Kidman’s outstanding performance, on par with her turn in Eyes Wide Shut, captures in every moment a woman overcome by lasting grief that never disappears. Through her character’s mourning, the full heartbreak of Birth dwells in the knowledge that her husband loved someone else more, and yet she cannot let go of his memory. With turns of tragedy rather than suspense, Glazer conceived and executes an inspired and sensitive drama that deserves reassessment as a carefully considered, masterfully made film that finds a place in its viewer and lingers there like a haunting dream.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review