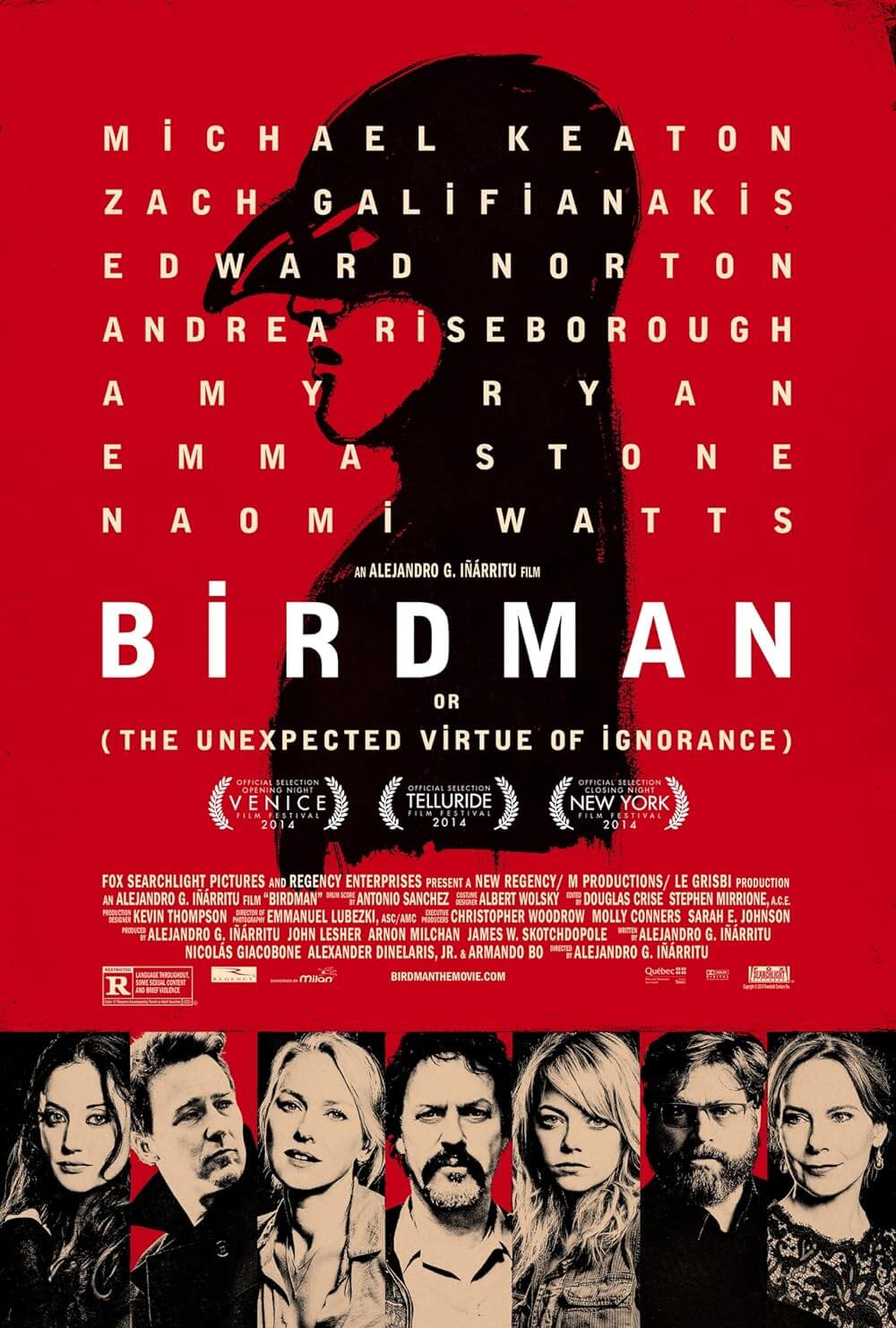

Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance)

By Brian Eggert |

Back in 1989, Michael Keaton starred in Batman and helped launch an era of superhero tentpoles designed for maximum commercial appeal and franchise potential, a trend that has only recently reached an all-consuming high in Hollywood. After the sequel, Batman Returns, he opted out of the cape and cowl, and despite some shining moments in Quentin Tarantino’s Jackie Brown and Steven Soderberg’s Out of Sight, Keaton’s post-Bat career has slipped away from him, and he’s rarely lived up to his potential. But all of his talent floats back to the surface in Alejandro González Iñárritu’s achingly self-referential Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance), in which Keaton plays a washed-up former superhero actor yearning for artistic recognition on Broadway, while his personal life falls apart around him. And while his character may not achieve validation gracefully, Keaton’s performance will likely give the real-life actor a needed revival.

Having five films to his name, Iñárritu collaborated with writer Guillermo Arriaga on three of them—Amores Perros, 21 Grams, and Babel—and then made Biutiful in 2010, all of them weighty, serious-minded, and “realistic” features. Iñárritu becomes downright playful, however, with Birdman, co-writing a bravado comic fantasy alongside his three co-writers: playwright Alexander Dinelaris Jr., Nicolas Giacobone, and Armando Bo. Driven by jazz drummer Antonio Sanchez’s frantic beats and distractingly virtuoso camerawork by cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, the film whirlwinds through the dressing rooms, stages, and rehearsals of an adaptation of Raymond Carver’s story “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love.” Riggin Thomson (Keaton), who starred in three “Birdman” movies back in the day, adapts, produces, directs, and stars in his Broadway debut, nervously overseeing every detail as though his very existence depends on it. And perhaps it does.

When we first meet Riggin, he’s floating (yes, floating) in child’s pose in his dressing room in St. James Theater on West 44th Street in New York. A voice in his head, deeper than Beetlejuice the morning after a bender, speaks to him, and tells him he’s making a mistake doing this play. They should be doing another “Birdman” movie, the voice says. A poster for “Birdman 3” hangs on the wall, a reminder of what he used to be. It’s too late to back out now. Riggin has put his own money into the production, as his manager Jake (Zach Galifianakis) reminds him. His cast relies on him, among them a Broadway newbie Lesley (Naomi Watts), his girlfriend Laura (Andrea Riseborough), and the last-minute new addition, the temperamental actor-with-a-capitol-A, Mike (Edward Norton). And while a backstage drama may not seem material heavy enough for Iñárritu, he brings a triumphant degree of visual and thematic artistry to the material, delivering a film comparable to Charlie Kaufman’s wonderfully wrapped-into-itself Synecdoche, New York or Federico Fellini’s whimsical 8½.

Ambitious comparisons though they may be, Birdman has a cheerier sense of humor, despite themes of artistic bankruptcy and suicide coursing through its veins. Consider a sequence where Riggin approaches an influential theater critic (Lindsay Duncan) and she announces her intention to berate his play out of spite for his former Hollywood status. He responds by insulting and paraphrases Gustave Flaubert: “A man becomes a critic when he cannot be an artist, as a man becomes an informant when he cannot be a soldier.” Though the scene is unbelievable (no self-respecting critic would form an opinion without seeing the end result), it feeds the film’s theme of Riggin’s desperate need for approval, yet his complete ignorance of the needs of those around him, coworkers and family alike. Riggin’s daughter Sam (Emma Stone), an ex-druggie who serves as his personal assistant, flirts with Mike and blames her father for never being there for her—and also labels him as a “nobody” because he avoids social media. Also cropping up is Riggin’s ex-wife Sylvia (Amy Ryan), reminding him why his relationships always fail.

Shot on location over 30 days after extensive rehearsals, Birdman flows from one sequence to the next, unbroken, and almost never stops to take a breath, except when the camera rises to the sky to watch the Sun rise and set. Indeed, the film is most impressive as a technical achievement in how Lubezki creates the illusion of one continuous, uninterrupted shot. It’s an effect to rival Hitchcock’s similar trick in Rope or Lubezki’s work on Children of Men and Gravity. His frame follows actors through narrow hallways, around cramped dressing rooms, up and down stairs, and into the rigging. The viewer, meanwhile, watches closely and tries to spot the cuts, which are either flawlessly disguised by editors Douglas Crise and Stephen Mirrione, or hidden by CGI. Whether the invisible camera positions itself behind two actors standing in front of a mirror or follows Riggin out into Times Square in his skivvies, we’re looking, perhaps too diligently, to see how Iñárritu and Lubezki have hidden their magic. Meanwhile, Birdman’s dramatic power feels overwhelmed by its formal bravado, even though the actors have dialed their performances up to 11 in order to capture the heightened theatricality of backstage dramaturgy.

Nevertheless, the film has a reflective—if not precognitive—purpose for Keaton by signifying the actor’s artistic breakthrough in Birdman after years out of the spotlight. During a second screening, the viewer may look beyond Iñárritu’s impressive, albeit diverting approach and appreciate the story and performances more. But rather than narrative direction, we’re saddled with these erratic characters and pulled this way and that, into scenes that, upon reflection, seem somewhat unimportant or random now—even though they were probably meticulously panned. Riggan’s frequent hallucinations and uncertain telekinetic abilities only weird-ify the film, in a good way, and further immerse us into the scatterbrained head of Keaton’s character. With hints of Gloria Swanson’s turn as Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard, Keaton plays a manic and certainly mad version of himself in a film whose unconventional treatment remains more admirable than truly engaging.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review