Biosphere

By Brian Eggert |

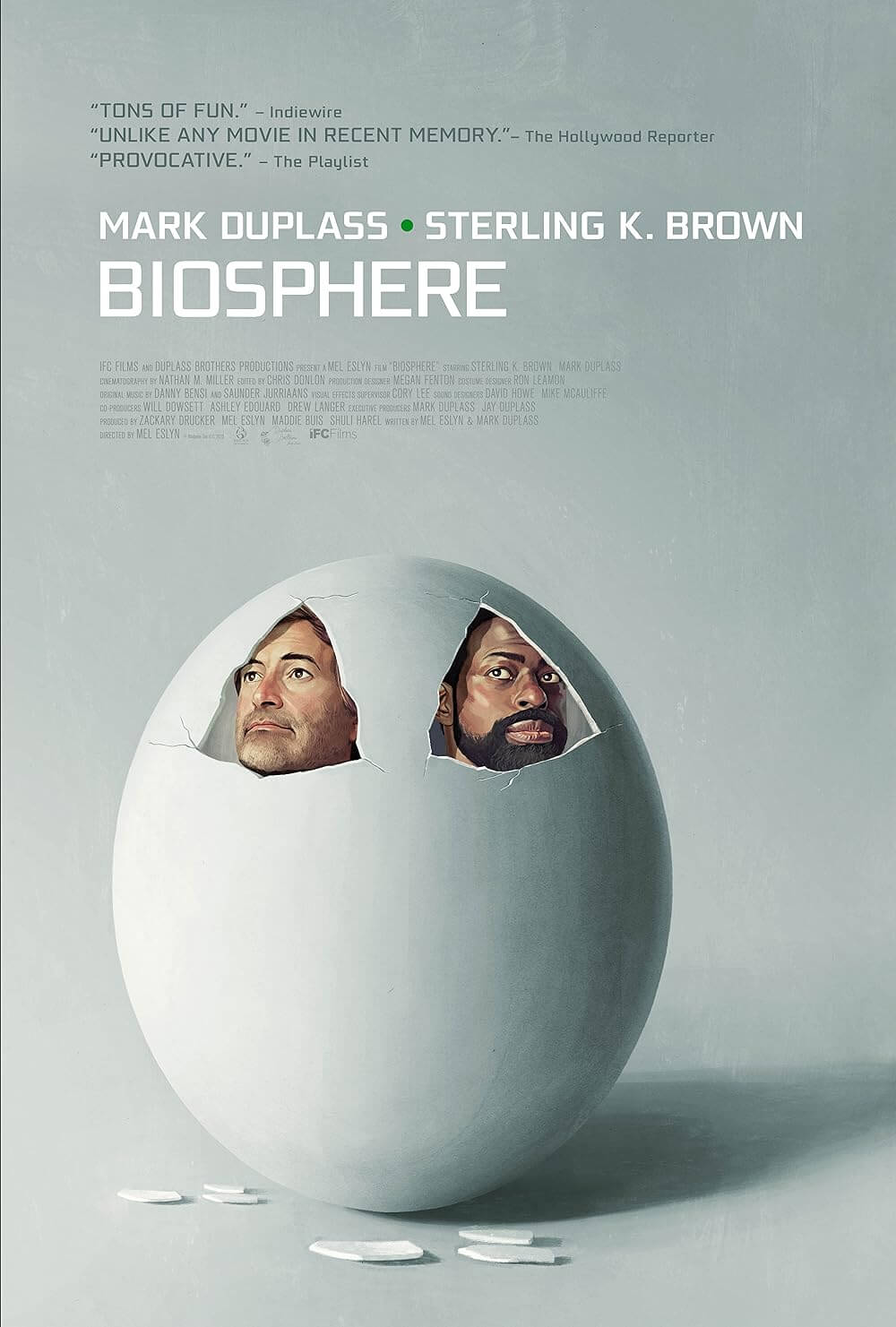

Mel Eslyn makes her feature debut with Biosphere, a smart comedy best entered blind. A longtime collaborator with the Duplass brothers, Mark and Jay, Eslyn runs their production company and has worked alongside filmmakers such as Jeff Baena (Spin Me Round, 2022) and the late Lynn Shelton (Laggies, 2014). Her transition to director is as effortless as they come, having co-written the script with Mark Duplass, who also stars alongside Sterling K. Brown. The seemingly straightforward concept, about two guys trapped in a closed ecological dome after some mysterious apocalyptic events, quite possibly making them the last two people on Earth, allows Eslyn to explore a slew of relationships and behavioral patterns. Although it’s a two-hander set in a single location, part of the fun is discovering how Eslyn and Duplass take the situation into wholly unexpected and unpredictable areas. So if you haven’t watched it yet, this review’s star rating should indicate that you should. Otherwise, consider yourself warned that this review will discuss those turns in some detail.

Set in the not-too-distant future, the film plays like Luis Buñuel’s take on Bio-Dome (1996). Brown and Duplass play lifelong friends, Ray and Billy, respectively. Ray is a clever scientist who built their abode, and Billy, by comparison, is a bit of a dunce. Still, there’s a power dynamic between them that Billy compares to Mario and Luigi, albeit indirectly, suggesting that Mario may be the face but Luigi is either equal to or even more important. So which one is the Mario, and which is the Luigi? We learn over time that Billy—despite not knowing the difference between “facetious” and “capricious”—used to be the President of the United States. Ray was his top scientific advisor. Some awful circumstances that remain unclear rendered the world outside unlivable and the sky shrouded in blackness, presumably a nuclear winter, and it’s almost certainly Billy’s fault. For the last fourteen months, they have kept to a steady routine: they jog around the circular interior perimeter, recalling a sequence out of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968); they play video games and watch movies to pass the time; they eat sparingly from their small hydroponic garden, fish pool, and store of dehydrated food.

Then things start to change. The last female fish dies, leaving the two remaining male fish unable to reproduce. So Ray and Billy will eventually run out of food. Around the same time, a green light appears in the otherwise impenetrable shroud outside, and as days pass, it seems to get larger. Is this some bad omen, or is it a beacon of hope like the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock in The Great Gatsby (1925)? Either way, it seems their long period of routine stagnation inside the dome will end with their starvation. The two men grapple with their mortality, and Billy, especially, doesn’t take it well. That is, until, as Billy quotes Jurassic Park (1993), “Life finds a way.” Just as dinosaurs evolved to procreate in that film, one of the last two fish rapidly changes from a male into a female, ensuring more fish, thus Ray and Billy’s survival.

Then things start to change. The last female fish dies, leaving the two remaining male fish unable to reproduce. So Ray and Billy will eventually run out of food. Around the same time, a green light appears in the otherwise impenetrable shroud outside, and as days pass, it seems to get larger. Is this some bad omen, or is it a beacon of hope like the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock in The Great Gatsby (1925)? Either way, it seems their long period of routine stagnation inside the dome will end with their starvation. The two men grapple with their mortality, and Billy, especially, doesn’t take it well. That is, until, as Billy quotes Jurassic Park (1993), “Life finds a way.” Just as dinosaurs evolved to procreate in that film, one of the last two fish rapidly changes from a male into a female, ensuring more fish, thus Ray and Billy’s survival.

The intertextuality doesn’t end with F. Scott Fitzgerald and Steven Spielberg; it also extends to Manuel Puig. Early in the film, Billy struggles through a copy of Puig’s Kiss of the Spider Woman (1976), comically yearning for more “beach reads” instead of the books Ray packed for them. But then, Billy doesn’t understand the book. Ray has to explain that it’s about two male prisoners, not a man and woman, as Billy initially thought. Gradually, Biosphere instills the idea of gender transformation and expands upon it, not only with the fish but when Billy, too, starts to recognize his body evolving into that of a woman out of a biological imperative. What begins as a familiar scenario quickly becomes an intelligent and out-there investigation of gender and power. How do the two heterosexual men, who constantly refer to each other as “Dude” and “Bro,” who have always based their friendship on masculine bonding rituals, reconcile this sudden change in gender and gendered behavior? Where does their relationship go from here? What do the designations of male and female mean, anyway? Do they have an obligation to explore procreation to save the human species?

The performances wonderfully accent these situational questions, as both Brown and Duplass give complex and hilariously nuanced turns. Sure, Eslyn and Duplass’ screenplay explores the comic limits of the premise, offering riotous moments of awkward, physical, and even surreal comedy. But Brown displays a wide range of emotions as an intelligent character tested by what he knows and doesn’t know, and who’s provoked by his emotional boundaries and initial homophobia. Duplass is excellent as a close-minded type whose sudden exposure to his feminine side makes him more self-aware and open to exploring their unique situation. Eslyn and cinematographer Nathan M. Miller contain these characters within a convincing location that underscores the intimacy necessitated between them, making scenes where they cut each other off all the more pronounced and poignant. Only a goofy dancing montage sequence feels out of place.

Using science fiction and comedy, Eslyn contributes her perspective, that of a queer woman, into situations that upend toxic masculinity and binary thinking. Beyond its Charlie Kaufman-esque setup, Biosphere argues that to survive in this increasingly harsh political and ecological environment of our own making, humanity must evolve and become more open to alternatives. It’s right there in the title, which applies to more than the sphere inhabited by Ray and Billy, but also the entire world’s ecosystem that, under heteronormative and patriarchal regimes, clearly hasn’t done too well. If that all sounds soap-boxy, it’s thoughtfully and subtly ingrained into the story and characters, making what could be a lofty subject into a small-scale allegory. Wildly funny, inventive, and thoughtful, Biosphere is one of the best original comedies in recent memory.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review