Big Eyes

By Brian Eggert |

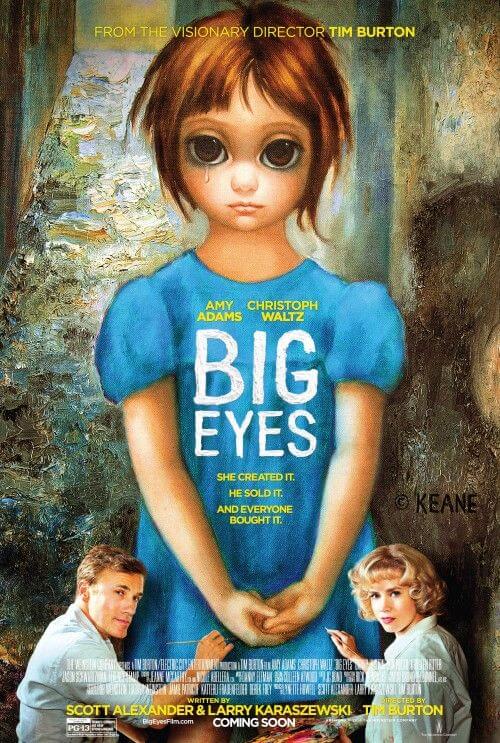

Eyes may be a window into the soul, but Big Eyes has virtually drawn the curtains on its subject matter, allowing audiences to see only a vague impression of what’s behind them. Concerning Walter Keane’s fraud in purporting that his wife Margaret’s paintings of glossy-eyed waifs were his own, the film paints in thick brushstrokes courtesy of Tim Burton’s direction and the broad screenplay treatment by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski, whose other biopics include Burton’s Ed Wood, and Milos Forman’s The People vs. Larry Flynt and Man on the Moon. Still, it’s an excellent-looking production steeped in 1950s and 1960s set and production design courtesy of Oscar winner Colleen Atwood. And the film entertains enough through the mere presences of Amy Adams and Christoph Waltz, both of whom never quite disappear into their performances, but provide ample star power to a film that doesn’t probe deep enough into its subject.

From the outset, the film distances the audience from its protagonist through a narrator device. Danny Huston plays Dick Nolan, a reporter telling the Keane story from who knows when; the Nolan character barely appears onscreen, and there are no framing scenes to tell us when or why Nolan is the storyteller. At any rate, the story begins in 1958 with Margaret Doris Hawkins Ulbrich (Adams) in Northern California as she leaves her abusive husband. She takes her young daughter Jane (Delaney Raye) and arrives in San Francisco near her friend (Krysten Ritter). A painter of children with unusually large, sad eyes, Margaret meets a fellow artist in Walter Keane (Waltz), a Sunday painter whose affinity for salesmanship makes him charming. When Margaret finds she’s being sued for custody of Jane, Walter, whom she’s now dating, suggests they get married.

Soon Margaret begins signing her paintings with her married name, Keane, and Walter takes credit for them when they’re displayed at a local jazz club. With his extroverted personality and endless lines of BS to back the works, they sell fast, allowing Walter to open an art gallery. But the paintings become so popular that he finds the common folk interested cannot afford gallery prices, so he begins to sell posters and prints for less, making oodles of cash in his operation. Meanwhile, Margaret, ever the dutiful yet quietly protesting wife, remains shocked and betrayed over Walter’s scheme, but she’s also afraid to lose Jane (played by Madeleine Arthur as a teen). “People don’t buy lady art,” Walter explains. Moreover, Margaret isn’t the salesman her husband is; she tries painting in another style (mostly elongated women, a style never explained onscreen), while also providing Walter with a regular supply of big-eyed waifs, and she’s unable to sell anything under her name alone. Sadly, Walter was right about the stigma around female painters in this era.

Margaret’s paintings may have represented her continued dismay with Walter through the desperation in her children’s eyes, but for much of the film, the character doesn’t fight back, which can grow aggravating for a viewer at all interested in a feminist protagonist. It’s difficult to imagine any wife who once had enough guts to leave her husband in the 1950s turn around and stay with someone like Walter for 10 years, and further, allow a corrosive lie to eat away at her. What was going through her head during these events? Big Eyes fails to penetrate its subject in that respect and prefers to showcase Walter’s buffoonish grandstanding through Waltz’s expressive performance. Eventually, Margaret leaves Walter and sues him in a wildly absurd court sequence where he represents himself, but we’re still left with questions about what motivates the art. There’s never a satisfactory counterargument to Jason Schwartzman’s snobby gallery curator or New York Times art critic John Canaday (Terence Stamp), both who find Margaret’s work popular tripe.

Andy Warhol said, “I think what Keane has done is terrific. If it were bad, so many people wouldn’t like it.” A lot of people watched Keeping Up with the Kardashians too, but that doesn’t mean it was the best television show around. Popularity does not denote quality, but perhaps my critical viewpoint is biased. Burton and company agree with Warhol’s quote; it opens the film, after all. But it’s worth questioning what popularity has to do with great art, if anything. Big Eyes never really addresses the art itself beyond the Warhol position. It shows us what other people thought about it, and it makes a heartfelt case for Margaret and her struggle to be sure, but the audience is left to decide how they feel about the art on their own. In a way, that’s an admirable position. But it’s also a very safe position. Of course, Burton’s own commercialized work like Alice in Wonderland and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is popular and despised by most critics too, so perhaps Burton is making an argument for his own films. If that’s the case, it’s a weak argument indeed.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review